Form follows Function

1920

1945

Overview

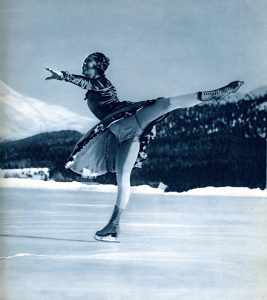

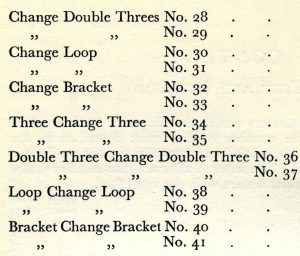

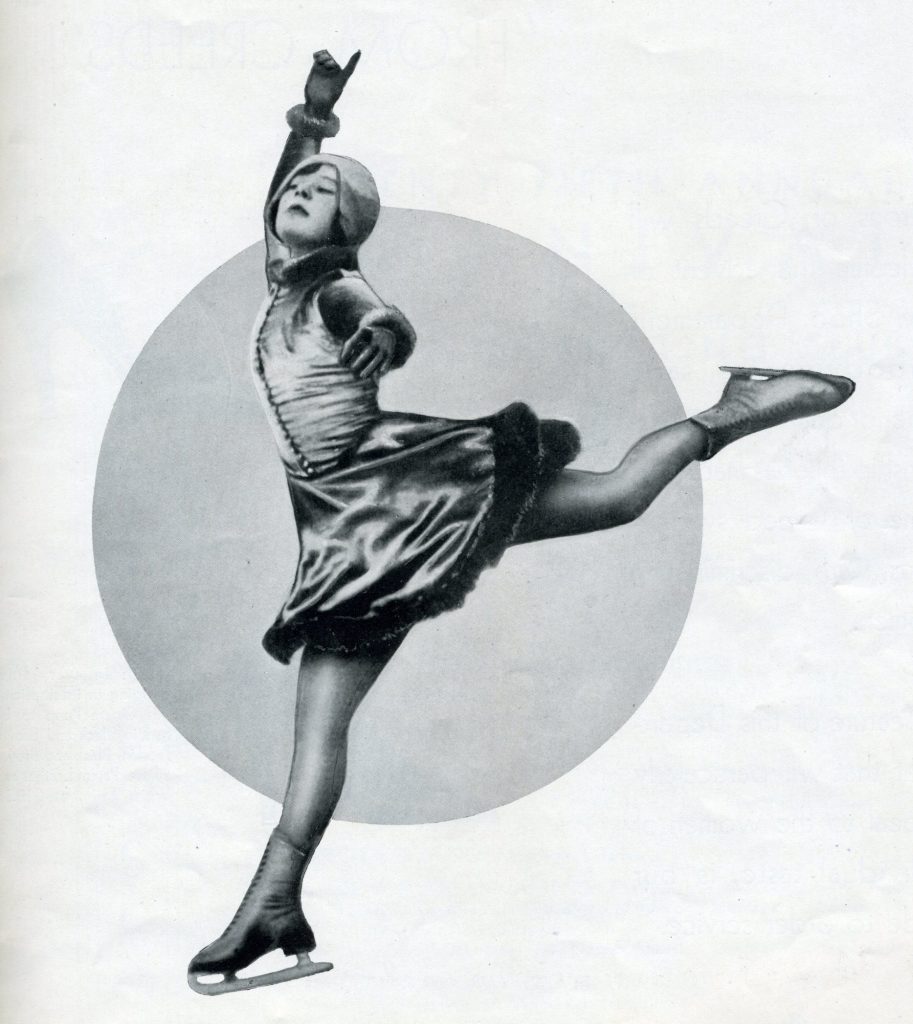

Sonja Henie doing a spiral, photo by Foto Blau. In Manfred Curry's "Schönheit des Eislaufs", Berlin: Paul Franke Verlag, 1934.

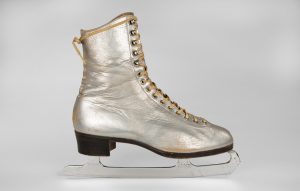

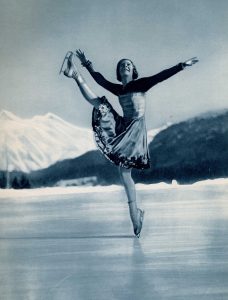

Sonja Henie’s skate in silver leather, likely worn during her post-competitive career. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P10.9

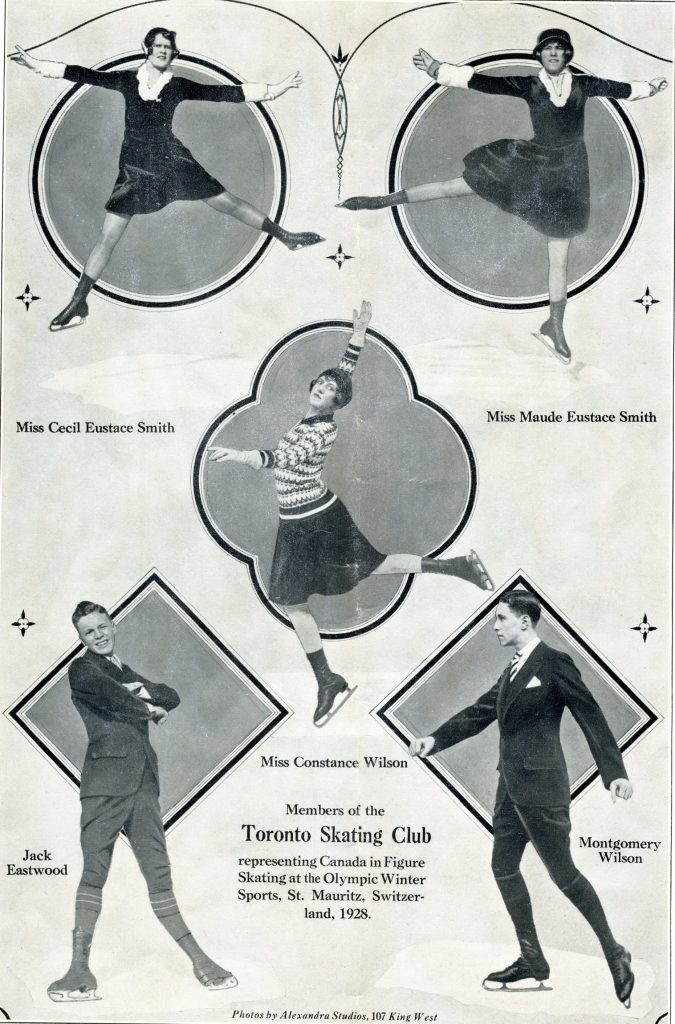

This era is the true beginning of figure skating. Although Canada joined the International Skating Union in 1894, British and European skaters still dominated at the Worlds and Olympics. Why? Geography! Travelling overseas was no easy feat—skaters had to take ships, trains, and buses to reach international competitions.

Page showing the five TSC Members representing Canada at the 1928 Olympics in St. Mauritz. Toronto Skating Club 21st Carnival Program, 1928. Photos by Alexandra Studios. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac.

International competitions were just beginning to be hosted on North American ice. Canada hosted the World Championships in Montreal in 1932. That same year, the USA hosted the Olympic Games in Lake Placid, New York.

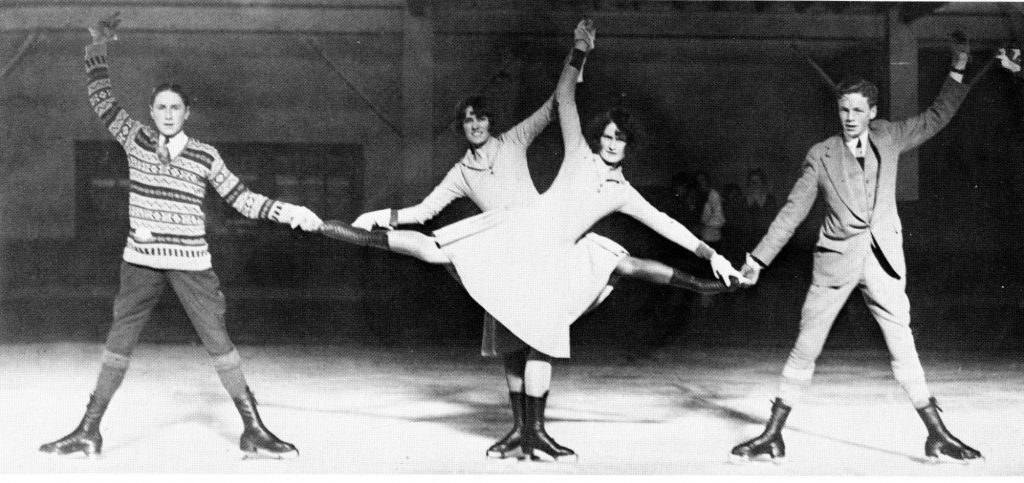

The 1920s was a period of change and liberation, even in skating. Fashion on the ice changed with the times. Women were finally able to exchange restrictive Edwardian dresses for shorter, free-flowing skirts. Men started wearing their formal jackets and ties with knee-length pants or dark wool tights.

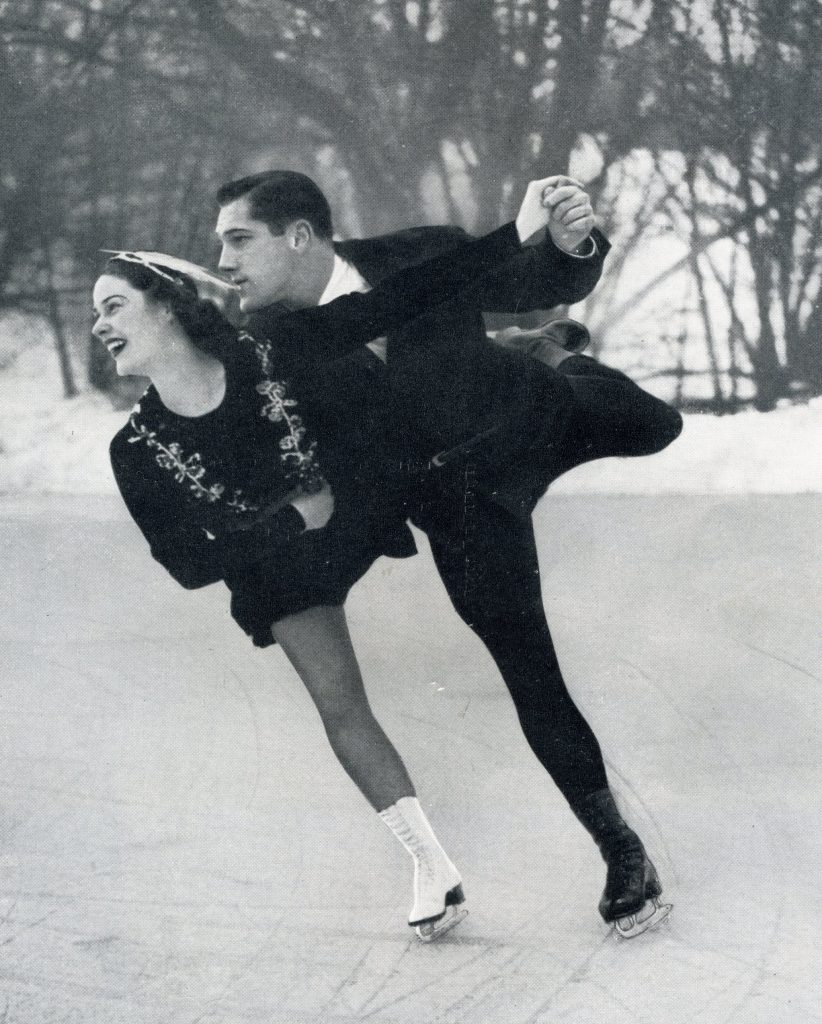

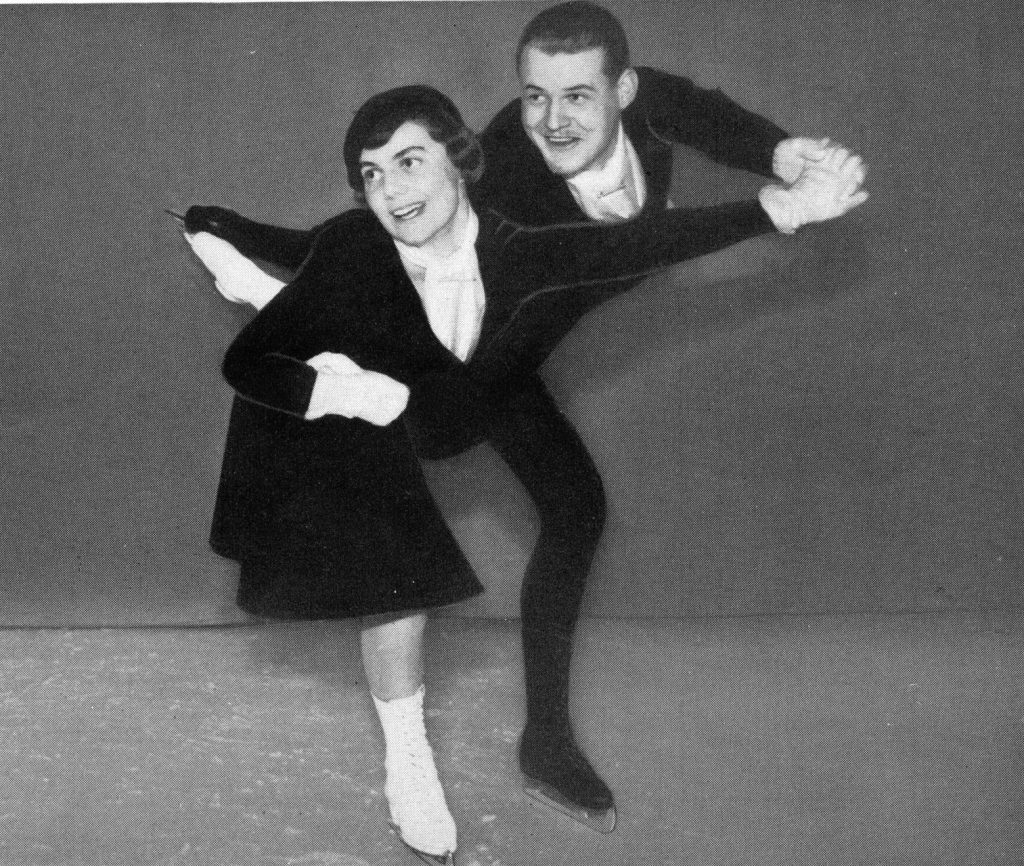

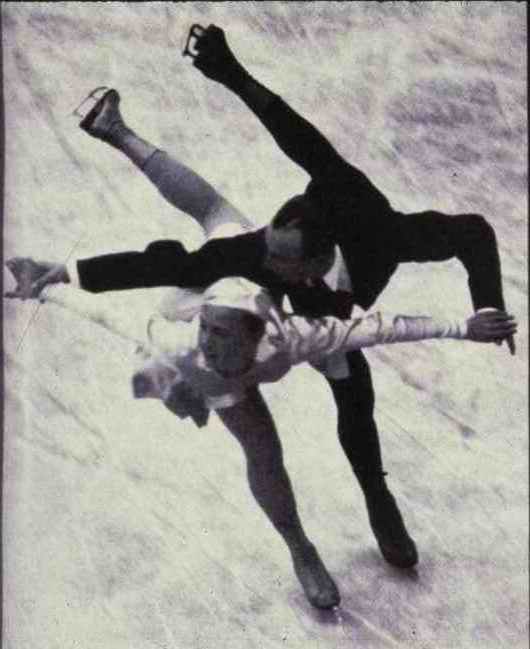

Eleanor O’Meara and Ralph McCreath, skating at the Toronto Skating Club’s 34th Carnival, 1941. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

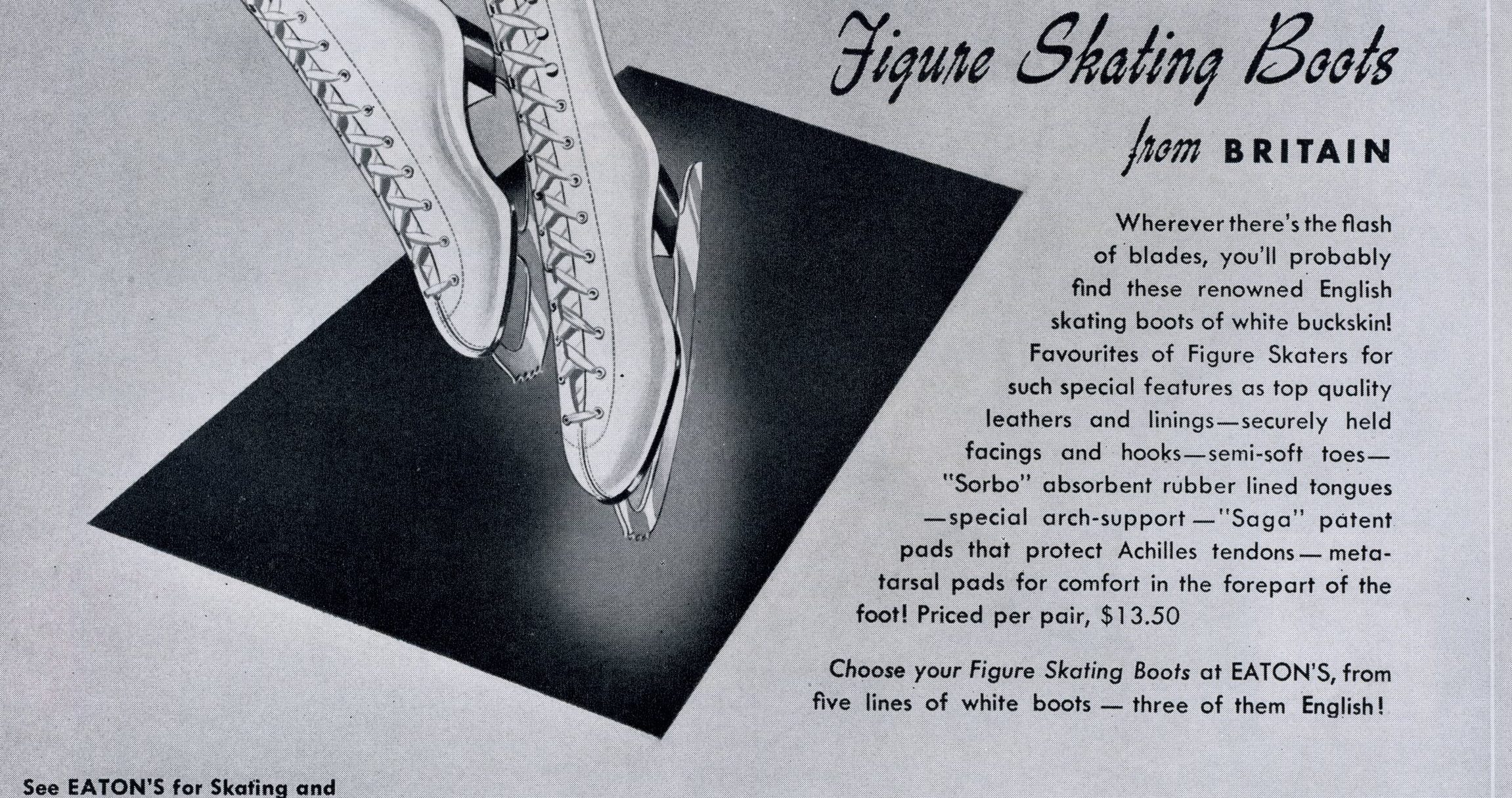

Boot and blade design changed as well. Women started to wear brilliant white leather boots to highlight their colourful costumes.

Competitive skating reached a new plateau when Canadian skaters won their first international medals.

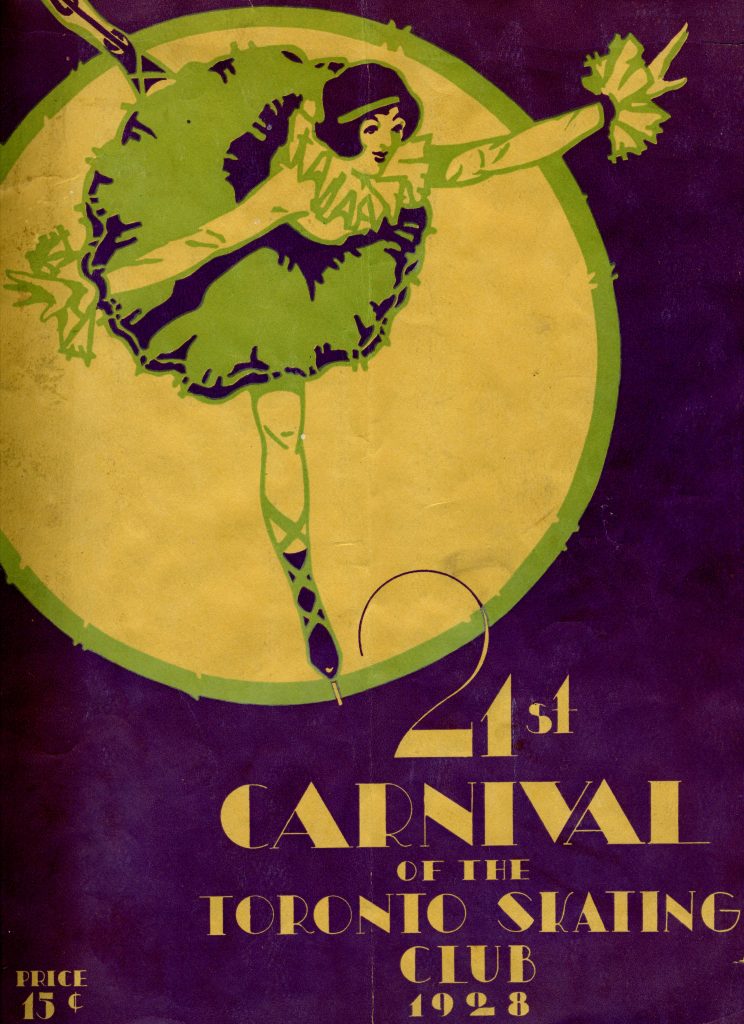

Program Cover, Toronto Skating Club 21st Carnival, 1928. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Audiences flocked to see the Toronto Skating Club’s dazzling skating carnivals. Touring professional ice shows founded in the late 1930s like the Ice Follies, Ice Capades, and Holiday on Ice wowed audiences across North America and Europe with their extravagance.

Corps de Ballet rehearsing for the 1930 Toronto Skating Club Carnival. City of Toronto Archives, Globe and Mail fonds, Fonds 1266, Item 48601

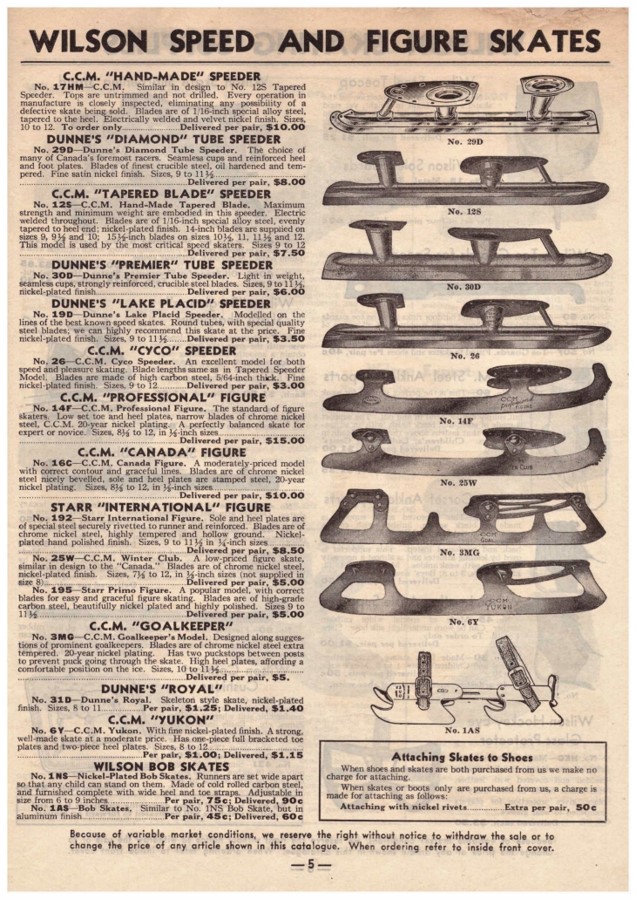

Boots & Blades

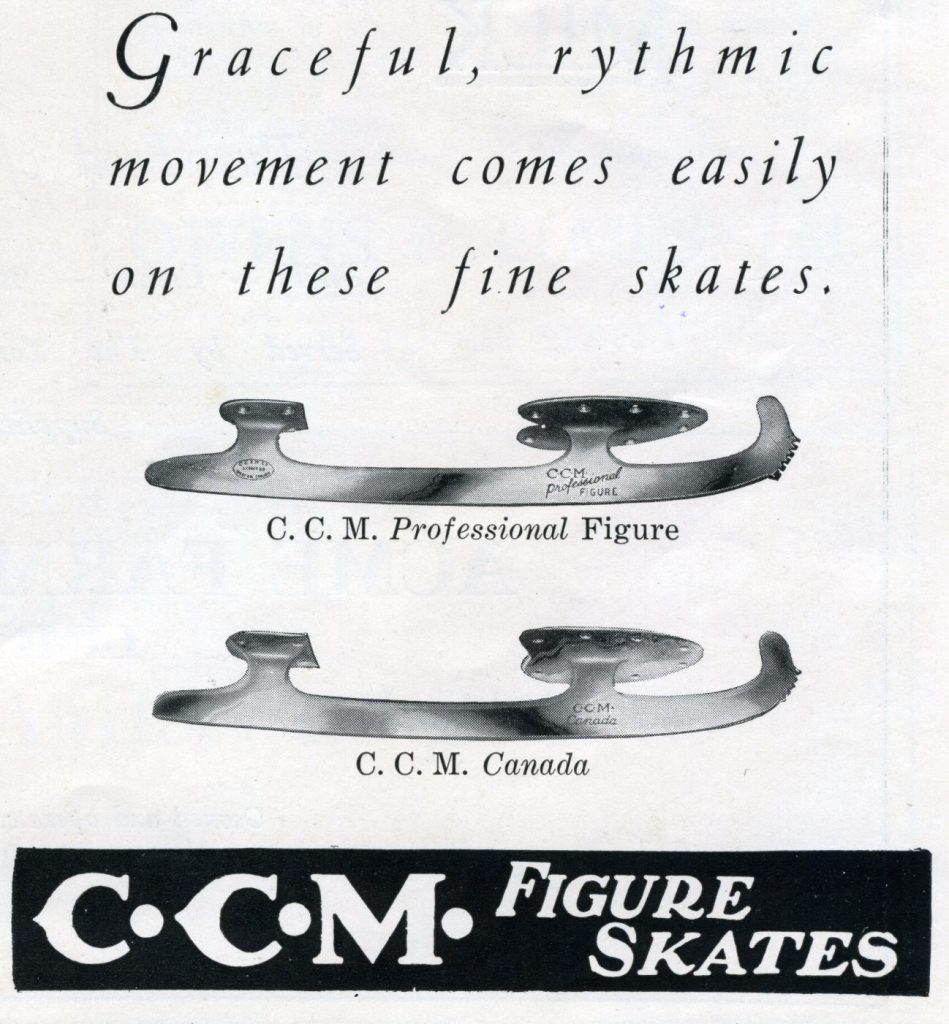

Canadians make both custom and mass-produced skates

Quebecois boot company Daoust Lalonde began to make skating boots in the late 1800s and by the 1930s were selling boot-and-blade sets.

The Starr Manufacturing company, creators of the Acme Spring Skate blade in 1863, closed their doors in 1939.

Anne Douglas’s CCM brand leisure skates, c. 1920s. Courtesy of Charlene Jordan

Anne Douglas enjoying outdoor leisure skating near Red Rock, Ontario, c. 1926. Courtesy Charlene Jordan

Several Canadian craftspeople were swift to fill the gap. Canadian custom shoemaker George Tackaberry (1874-1937) developed a new hockey boot in 1905, using kangaroo leather instead of the more traditional cowhide. The “Tack” boot became so popular that hockey-equipment company CCM acquired the patent in 1937 and started mass manufacturing it.

In his book Canada Cycle and Motor: The CCM Story, author John A McKenty recounts the popularity of the CCM skate. Champion Canadian figure skater Montgomery (Bud) Wilson endorsed the brand. Norwegian figure-skating great Sonja Henie ordered 80 pairs of CCM skates for her touring company the Hollywood Ice Revue.

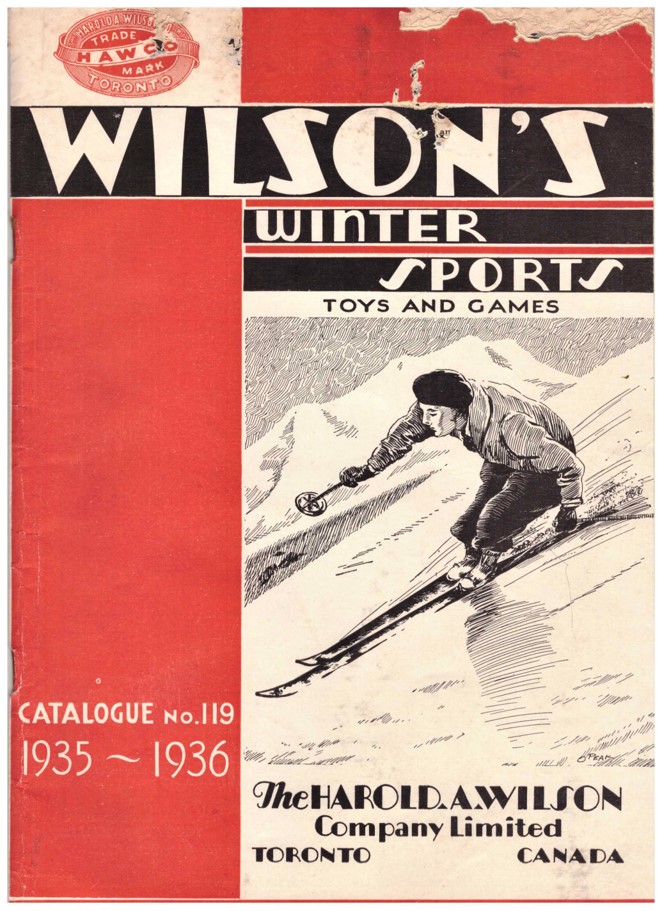

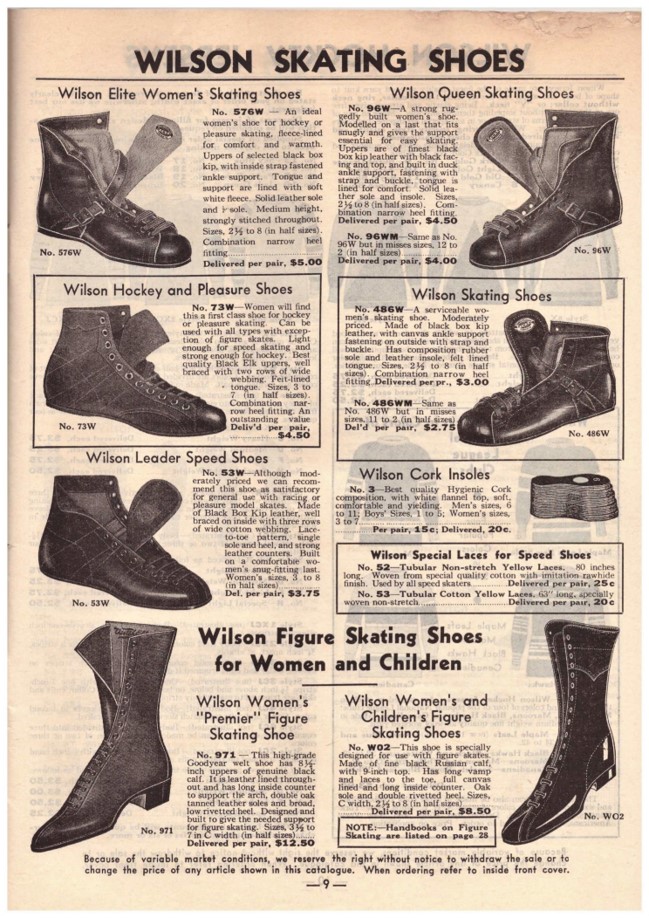

Other Canadian companies proved popular. The Harold A. Wilson Company Limited, located in Toronto, marketed their figure-skating boots, accessories, and blades through a mail-order catalogue. Harold A. Wilson carried blades produced by CCM and Starr Manufacturing. The Eaton’s department store advertised skates in their catalogues as well.

“Figure Skating Boots from Britain” advertisement by Eaton’s department store, 1941, showing white buckskin boots with blades attached. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac.

Why were women not allowed to jump in figure skating until the 1920s?

Why were women not allowed to jump in figure skating until the 1920s?

Skating was a male-dominated sport up until the 1920s, and before WWI, society required that women wear long skirts, which made jumping extremely difficult.

The evolution of boot and blade design

German Fuchs brand women’s skates in black. The sole is marked “Wasserdicht”, identifying the boot as waterproof. The blade has an extended toe with pick that was popular at the time, c. 1930-1939. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S86.162

Maribel Vinson Owen, in her Primer of Figure Skating, described 1930s skating boots in this way:

“A figure-skating boot is much higher and supporting than the common hockey boot. It is about 9 inches in height for men’s boots and 8 inches in height for women’s. It must fit so snugly that your heel does not slip up or down the least bit, even when the boot is loosely laced. The fit through the instep up to the back of the big-toe joint must be equally tight. There should be no wrinkles from the instep back to the heel over the anklebone and, most important, there should be a wide spread of 1 inch and 1 ½ inches between the lacings over the instep, even when the boot is laced up.”

Scroll across the screen here to see skates from the early 1900s in the Bata Shoe Museum Collection:

Boot colours became more varied during the 1930s. White boots slowly replaced brown, black, and tan leather boots. Maribel Vinson Owen noted that women in particular were adopting white boots because “they look best with a wide range of coloured costumes, which may be white or pastel or a vivid splash of colour.”

The top Canadian skaters often wore boots and blades from American, British, and European makers.

Sonja Henie’s silver leather figure skates, custom made by Stanzione of New York City. The blades are by Strauss of St Paul, Minnesota. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P10.9

A close up of the blade showing the ‘Strauss’ mark. ‘SONJA’ is impressed on the blade at the heel. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P10.9

Italian American shoemaker Gustavo Stanzione produced custom-made skating boots starting in 1905. American skate-blade craftsman and metalworker John Strauss was still producing his signature blade well into the 1900s. A Stanzione boot with a Strauss blade proved a popular choice amongst the sport’s top athletes.

Movement

Evolution of Skating Styles

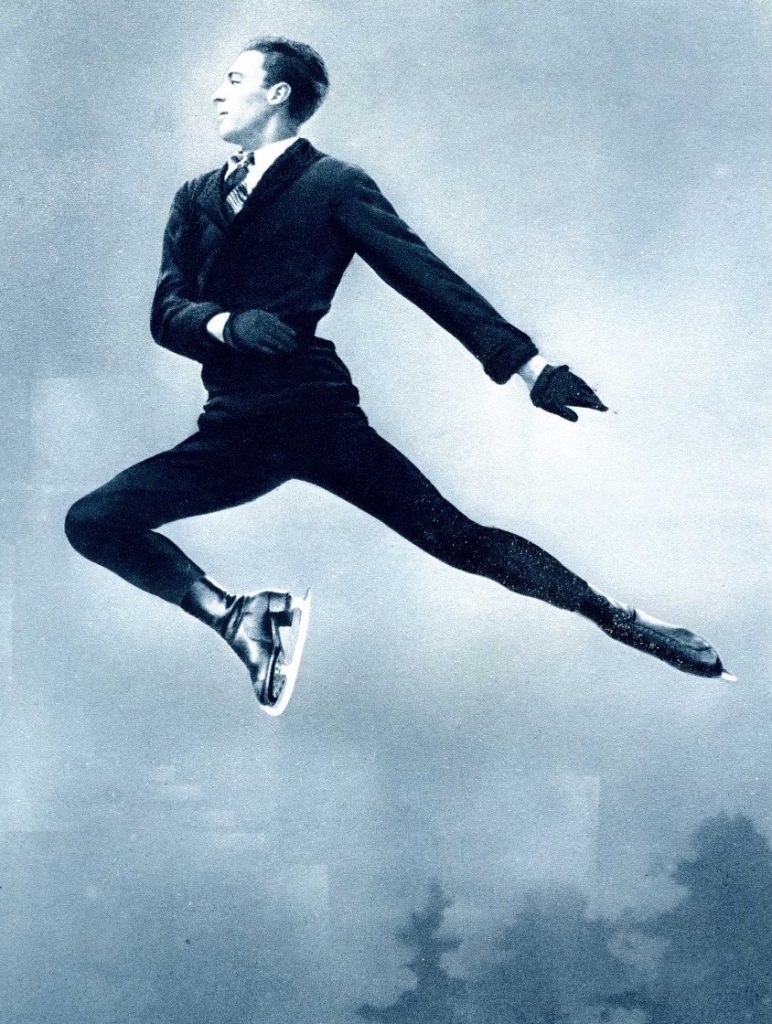

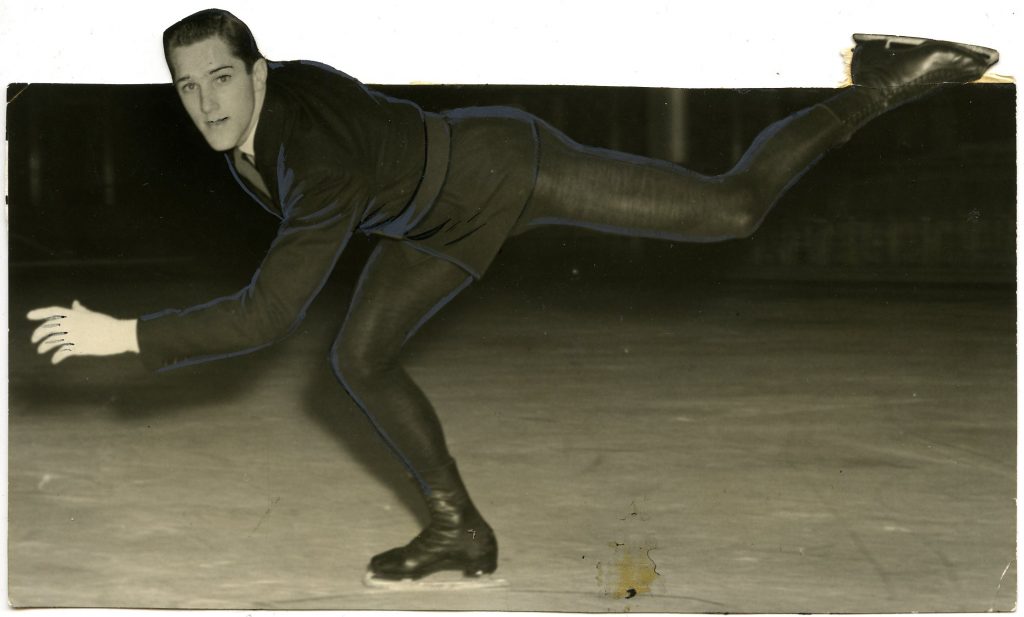

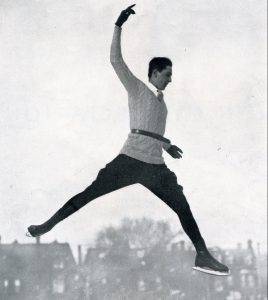

Ralph McCreath showing the “bent-knee aesthetic”, c. mid-1940s. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Artistic skating positions could be described as having a “bent-knee aesthetic”. The bodyline of ballet arm movement and elongated leg positions were not yet part of the figure skating.

A. Single Skating

Single skaters competed in two categories: compulsory figures and free skating.

Compulsory Figures for Single Skating

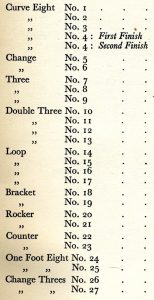

Official ISU names and numbers for the figures 1 through 27. In Nicholson on Figure Skating by Howard Nicholson, London, 1932 p.xiii.

Official ISU names and numbers for the figures 28 through 41. In Nicholson on Figure Skating by Howard Nicholson, London, 1932 p.xiii.

Skaters needed to practise and perfect 41 compulsory figures from the International Skating Union (ISU) rulebook. Of these 41 elements, the ISU chose 12 of them to test competitors on. Can you imagine having to practise that many tracings? It would take two days to perform all the 12 figures in front of judges. Compulsory figures accounted for 60% of a skater’s marks.

Sonja Henie (1912-1969)

One of the skating world’s first celebrities, champion Norwegian figure skater Sonja Henie drew huge audiences with her poetic skating. Henie used her ballet background to create glamorous and artistic performances.

Henie holds the most Olympic and World Championship titles of any female figure skater. She won her first Worlds title when she was only 14, her first win in a series of ten. She would go on to win three Olympic Games. She was one of the first women to land an Axel, one of the most difficult jumps at the time. Her performances were so popular that the police were often called in for crowd control.

Henie was one of the first female skaters to wear a skirt above the knee. She also changed her boot colour to a striking white, which later became the norm for female skaters.

Sonja Henie: Ice Shows

After her amateur career, Henie performed professionally and also produced ice shows. Her lavish Hollywood Ice Revue packed Rockefeller Centre. She branched out into acting, appearing in over a dozen musical-comedy films opposite movie stars Cesar Romero, Tyrone Power, and Ethel Merman.

As a celebrity, Henie endorsed many products. She marketed skates, clothing, and even dolls!

Who was the first Canadian skater to win a medal at both the Worlds and the Winter Olympic Games?

Who was the first Canadian skater to win a medal at both the Worlds and the Winter Olympic Games?

Montgomery (Bud) Wilson won the bronze at the Winter Olympics and the silver at the Worlds in 1932. He was the first Canadian to secure a silver medal win in a men’s event at the Worlds.

Free Skating for Single Skating

Skaters expressed their personalities by creating new jumps and spins in free skating. Programs were set to music, lasting five minutes for men and four minutes for women. Skaters who were nimble connected their movements to create a smooth program. Free skating routines made up 40% of a skater’s marks.

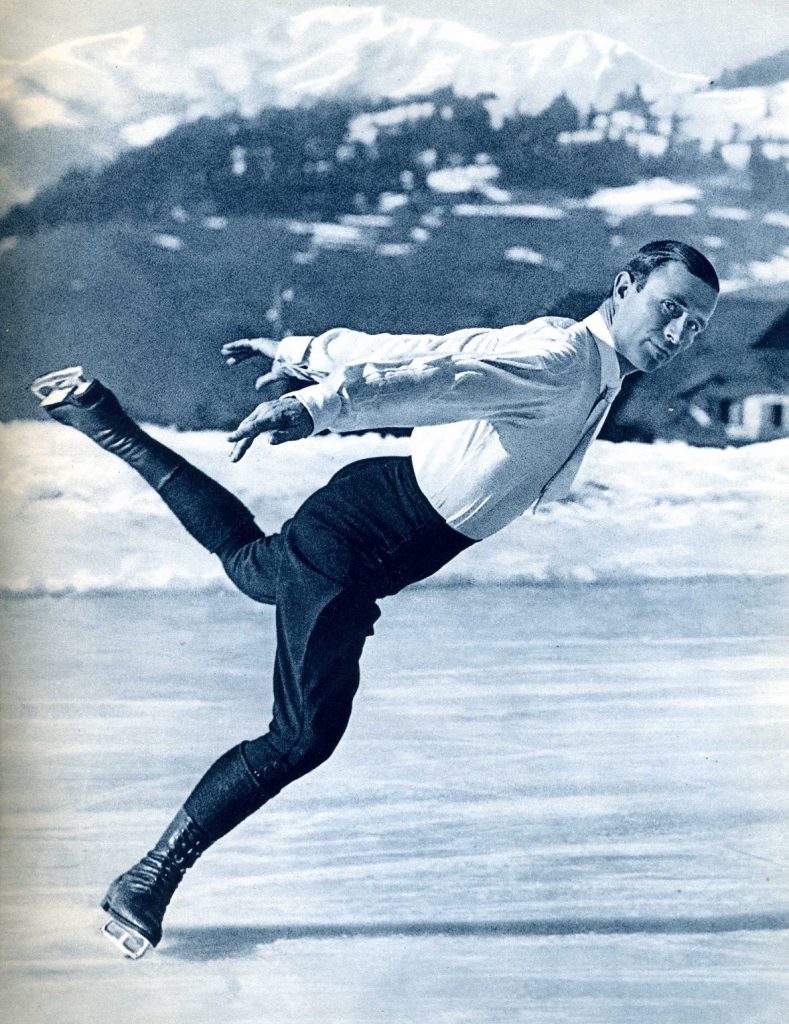

International Men

Swedish skater Gillis Grafström, who was also a poet, combined his artistic esthetic with powerful athleticism on the ice. He perfected the Axel jump and invented the flying sit spin: a challenging move where the skater jumps and lands in a spin. In a rather amusing incident, Grafström’s skates broke when he was on ice in Antwerp to compete in the 1920 Olympics. Although he was only able to buy an old-fashioned pair of ice skates, he seized the win!

Austrian Karl Schäfer’s debonair demeanor on the ice made him a popular athlete. He created the scratch spin, one of the most common spins in skating. In a scratch spin, the skater travels backwards for speed and steps forwards into the spin. The free foot is brought in towards the spinning knee and slowly lowers, creating a faster spin as it lowers. Schäfer would go on to coach in his native Austria, creating his own ice show called the Schäfer Ice Show.

B. Pair Skating

Constance Wilson-Samuel and Montgomery Wilson © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Isobel and Melville Rogers, the winning pair at a competition in Ottawa, 1927. Library and Archives Canada / PA-43676

Pair skating was divided into two distinct forms. Some skaters preferred shadow skating, where two skaters mirrored each other on the ice. The other form held that skaters had to hold hands or link arms throughout their program, taking cues from ballroom dancing. Pair skating programs were five minutes long and set to music.

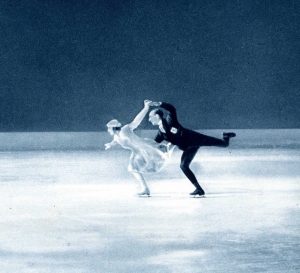

International Pairs : Andrée Joly and Pierre Brunet

Three-time World-champion Parisian pair skaters Andrée Joly and Pierre Brunet were consummate performers. They packed their Olympic performances in 1924, 1928, and 1932 with all types of intricate tricks and skating elements. Their energetic, intricate style caught on with other pair skaters.

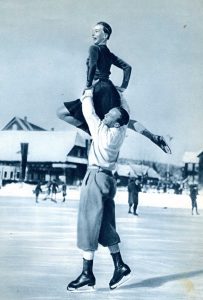

International Pairs : Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier

Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier were the top German pair skaters in the 1930s. Herber was 15 when the pair won their first Olympic medal. They were the first pair to jump side by side together on the ice, using the technique of shadow skating.

C. Ice Dancing

Louise Bertram and Stewart Reburn, Ice Dancers as well as Pair Champions of Canada, at the Toronto Skating Club’s 27th Carnival, 1935. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Each new skating season brought new ice dances with it. Can you imagine whirling across the ice to the sounds of a live band playing waltzes? Tea-dance socials were a popular weekend pastime. Soon, ice dancing elements became part of local skating competitions. However, ice dancing did not become an official competitive category until the 1950s.

Toronto becomes a training hub for skaters

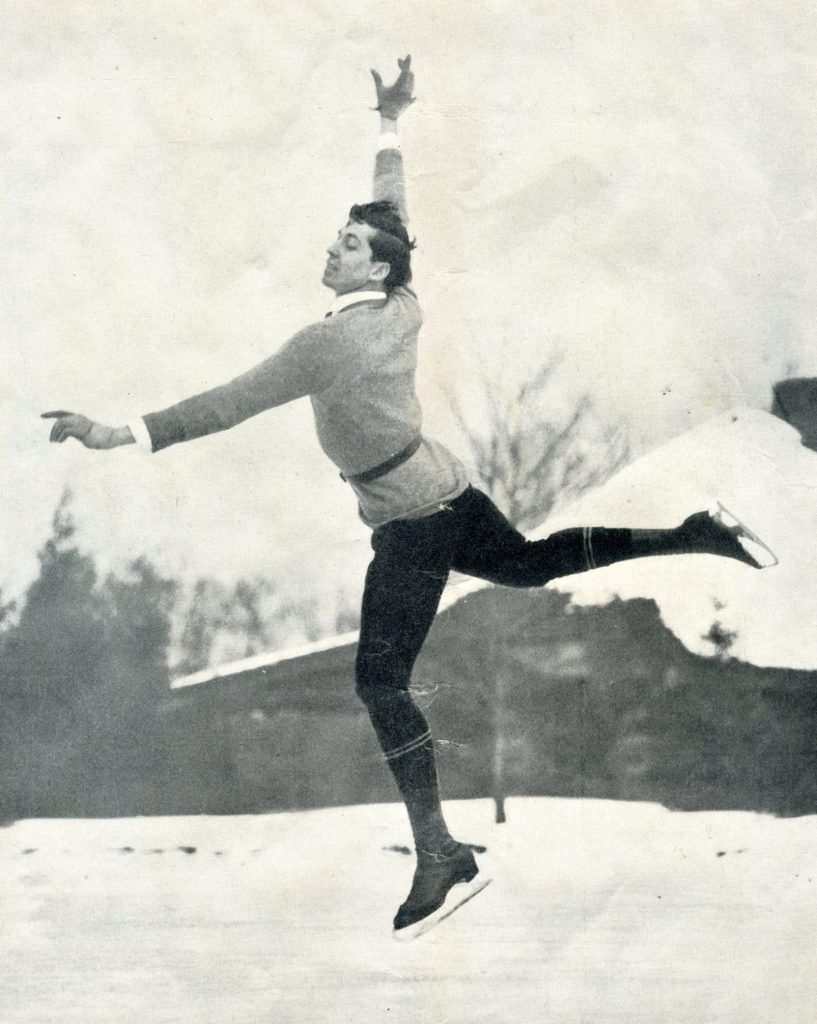

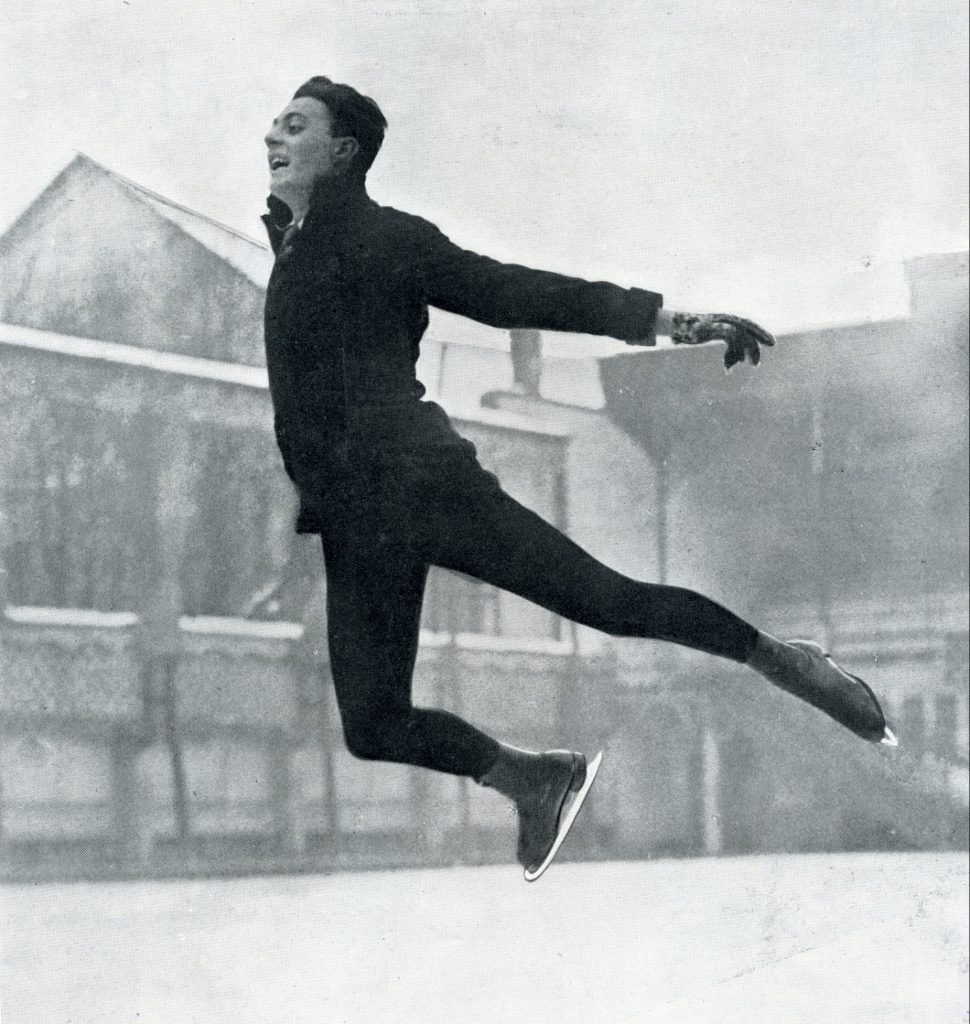

Gustave Lussi, Instructor, Toronto Skating Club, performing at the TSC’s 21st Carnival, 1928. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Skaters had to practise complex figures and tracings in order to perfect their routines. Where would figure skaters train during this time? Artificial indoor rinks and natural outdoor rinks were both popular venues in the 1920s.

Practising at these facilities often came at a disadvantage. Figure skaters had to share the same facility with hockey teams and leisure skaters. Although each sport had a dedicated ice time, it meant that there was not enough time to practise.

Constance Wilson-Samuel, Toronto Skating Club 27th Carnival, 1934. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Three skating venues in Toronto gave figure skaters the ice time they needed. The Toronto Skating Club, the Granite Club, and Varsity Arena were dedicated places for figure skaters to train.

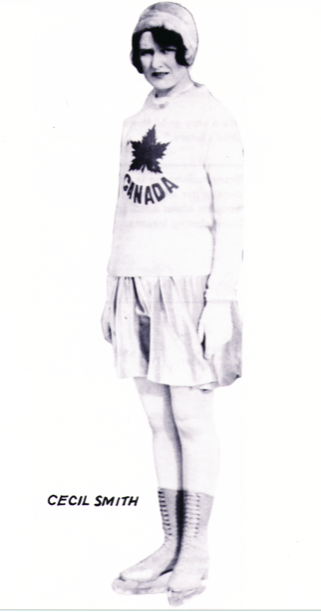

Cecil Eustace Smith at the Olympic Winter Games, 1928. © Skate Canada

The Toronto Skating Club (TSC) was the first club in Canada to offer a space exclusively for figure skaters. Canadian figure skaters could now propel themselves to new heights by having access to such a space.

Constance Wilson-Samuels and Bud Wilson, photo by International News Photos, New York. In Manfred Curry’s “Schönheit des Eislaufs”, Berlin: Paul Franke Verlag, 1934.

Since the Club’s members could now practise whenever they wished, new coaches were hired. Canadian champions like Montgomery (Bud) Wilson, Cecil Smith, and Constance Wilson-Samuel trained with international skating champions. They worked together and exchanged their ideas and techniques.

Swiss figure skater Gustave Lussi and Wilson developed a new jump called a “flip.” Celebrated Austrian skater Walter Arian trained junior skaters in elaborate routines for the Club’s annual carnival. Other familiar faces on the ice included German-born Walter Rittberger and Czech champion Otto Gold.

Werner Rittberger, Senior Instructor, Toronto Skating Club, at the TSC’s 25th Carnival, 1932. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Gustave Lussi later relocated to Lake Placid, New York. He opened up a summer skating school where top Canadian and American skaters could train year-round.

Many Canadian skaters competed in a skating category called “fours.” Fours was a form unique to Canada and the USA. In fours, two pairs of skaters would free-skate with music, mirroring each other’s movements. The category was later retired in 1949.

Who was the first Canadian skater to win a medal at the World Championships?

Who was the first Canadian skater to win a medal at the World Championships?

Champion female figure skater Cecil Eustace Smith placed second in the 1930 World Championships. She earned Canada’s first Worlds medal in a women’s category.

Costume

Liberation in Skating Outfits

Freedom at last! In the 1920s, women could trade in their long Edwardian skirts for shorter, colourful, pleated skirts. American figure skater and coach Maribel Vinson Owen outlined her general advice for women’s attire on the ice. She wrote in her book Primer of Figure Skating in 1938 that, “big hats are out of place on the ice. The closer fitting the cap or turban the trimmer the appearance. Bloomers should as a general rule match the skirt and should extend several inches down the leg.”

Mary Marks’ black wool skating dress, 1940s. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

Fashion changed for men, too. Men wore shorter pants called knickerbockers while training. For performances, black tights, white collars, neckties, and jackets were essential attire for the gentleman skater. As Maribel Vinson Owen wrote in her book, “For competition, black or dark-blue tights are de rigueur.”

Toronto Skating Club sets the precedent for professional ice shows

Let the show begin!

“Ballet of the Silver Spheres”, Toronto Skating Club 27th Carnival, 1934. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Maude Smith, Toronto Skating Club 27th Carnival, 1934. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

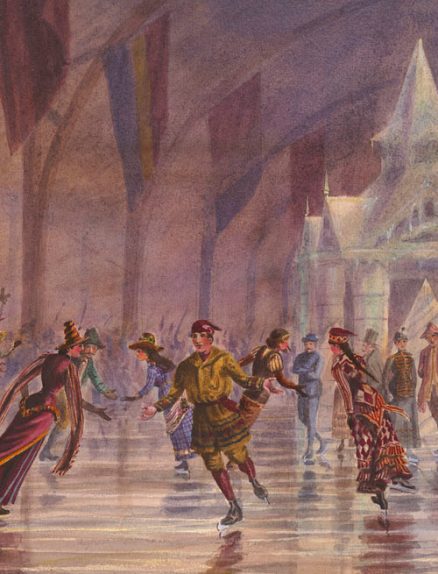

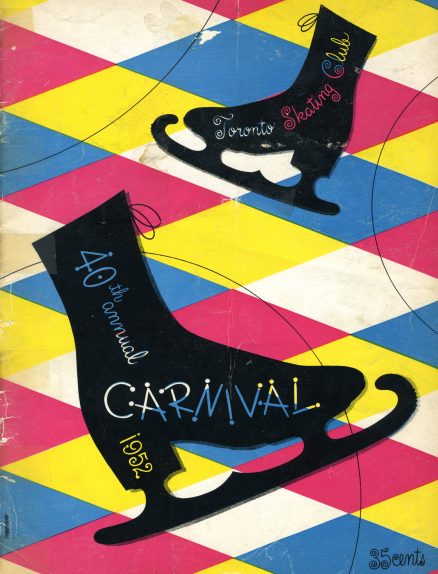

Starting in 1895, skating masquerade balls, and later carnivals, became a popular form of entertainment for figure and leisure skaters alike. Throughout the 1900s the Toronto Skating Club’s carnivals were a massive hit for audiences that would come from across North America. On a few occasions, the carnivals travelled to other cities!

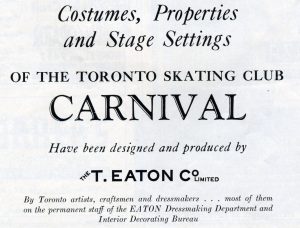

T. Eaton Co. advertisement in the Toronto Skating Club Carnival Program, 1939. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

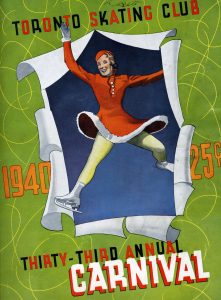

Cover, Toronto Skating Club Carnival program, 1940. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

These carnivals were the forerunner of the blossoming professional ice shows of the late 1930s and the 1940s. The Club was on the leading edge of production design for skating revues. Their huge themed productions featured towering set pieces, dramatic ultraviolet stage lighting, coloured ice, and sequin-spangled costumes.

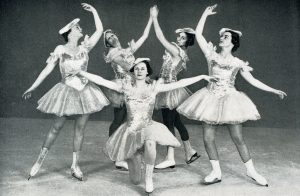

“Ballet Caprice”, Toronto Skating Club 28th Carnival, 1935. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

“Corps de Ballet”, Toronto Skating Club 33rd Carnival, 1940. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

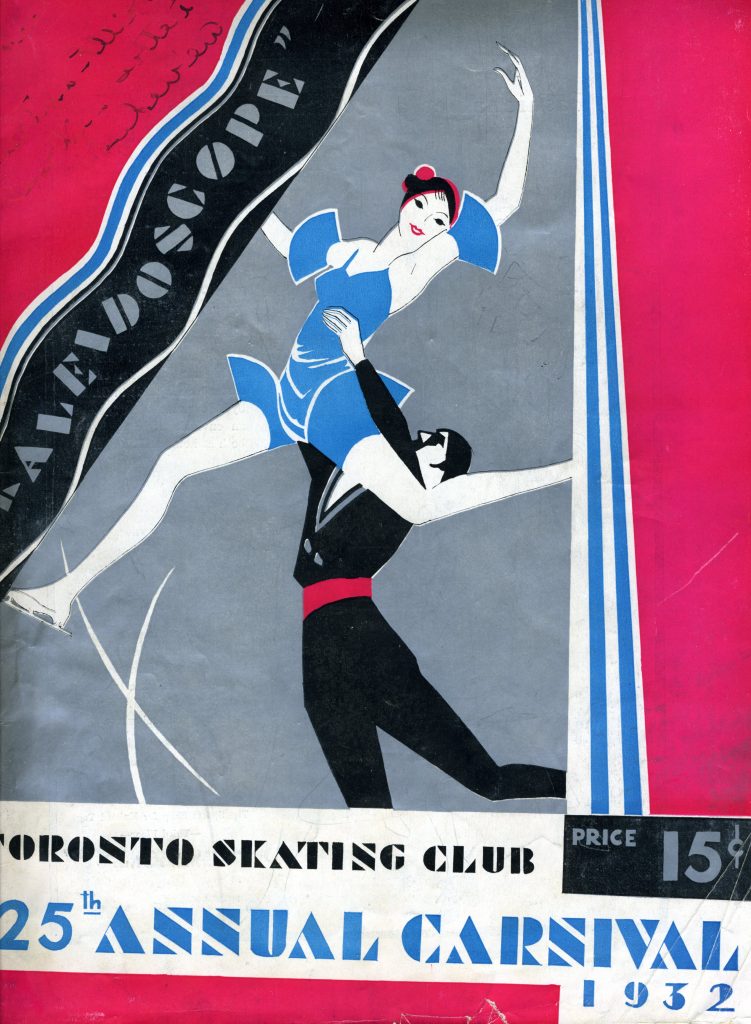

The Toronto Skating Club held its annual carnival at the Arena Gardens in the core of the city, rather than at the Club’s ice rink because there was no seating there. In 1932, the carnival moved to Maple Leaf Gardens to accommodate an even larger audience. Tickets for these productions sold out within days, and it was standing room only for any extra audience members.

Program cover, Toronto Skating Club 25th Carnival, 1932. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Celebrity skaters were invited to join the carnival. European stars Sonja Henie, Karl Schäfer, Andrée Joly, and Pierre Brunet performed alongside Canadian greats Montgomery (Bud) Wilson, Constance Wilson-Samuel, and Cecil Eustace Smith.

Sonja Henie performs at Toronto Skating Club’s 25th Carnival, 1932. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Andrée Joly and Pierre Brunet perform at Toronto Skating Club 32nd Carnival, 1939. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

The Toronto-based ballet master Boris Volkoff choreographed 14 seasons of the Club’s carnival. He adapted the ballets Swan Lake and Prince Igor for the ice, later adapting more experimental pieces by Rachmaninoff and Maurice Ravel’s Bolero. Volkoff himself could not skate. Contemporary accounts described him sliding across the ice to give skaters direction, a cushion tied to the seat of his pants in case he fell. Volkoff was the founder of the first ballet company in Canada, the Boris Volkoff Ballet Company.

These carnivals helped Canadian causes. During WWII, carnival proceeds went toward the war effort. The Club donated to the Red Cross and became the sole sponsor of wartime blood-donor clinics.

These shows would continue after WWII until 1956.

Who was the only Canadian skater to win the British Championships?

Who was the only Canadian skater to win the British Championships?

Constance Wilson-Samuel was the only Canadian woman to win the British Championships in 1928. The British Championships were then open to skaters from the Commonwealth.

Music

From orchestras to records

Wind-up gramophones were introduced to skating in the 1920s and 1930s. Sound systems were set up beside the ice, consisting of a record player (at that time called a gramophone), amplifiers, and speakers. The music that floated across the ice tended to become warped and distorted due to conditions on outdoor rinks.

Gillis Grafström, photo by E. Meerkämper, Davos. In Manfred Curry’s “Schönheit des Eislaufs”, Berlin: Paul Franke Verlag, 1934.

In 1911 World champion Lily Kronberger of Hungary brought her own military orchestra to the competition in Vienna to accompany her free-skating performance because she felt it was important for interpretation. Kronberger was an early innovator in music interpretation. It would be years until her influence caught on, as other skaters only started using music to dramatic effect in the 1940s. Nigel Brown writes in his seminal book, Ice-Skating: A History, in 1959:

“It is a curious fact that after Lily Kronberger’s experiment, musical interpretation did not receive the important place that it should have among the leading skaters that were to follow. For more than three decades music remained in the background of the free skating programs.”

Karl Schäfer at the Toronto Skating Club’s 25th Carnival, 1932. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Indeed, it was with live musical accompaniment that skaters with musical knowledge created expressive interpretations of their free-skating programs. For instance, Austrian skater Karl Schäfer, who was also a violinist, blended his musical and athletic abilities to create poetic routines in the 1920s and early 1930s. Also, Swedish skater Gillis Grafström, who was a poet as well, used musical interpretation and costume as part of his skating style in the same period.

Sonja Henie at the Toronto Skating Club’s 27th Carnival, 1934. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Skaters with a balletic background interpreted their musical choices with grace and poise using edges, jumps, and spins. In fact, Norwegian Sonja Henie had her own skating routine set to the music of Johann Strauss, recorded on a 78 RPM record for her in 1932 by Jack Hylton and his orchestra on the Decca label in England. Other skaters, like Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier, followed Henie’s lead.

Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier at the Olympics, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, 1936. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

By the end of this period, musical interpretation became a hallmark of interpretative skating.