The Artistic Revolution

1965

1985

Overview

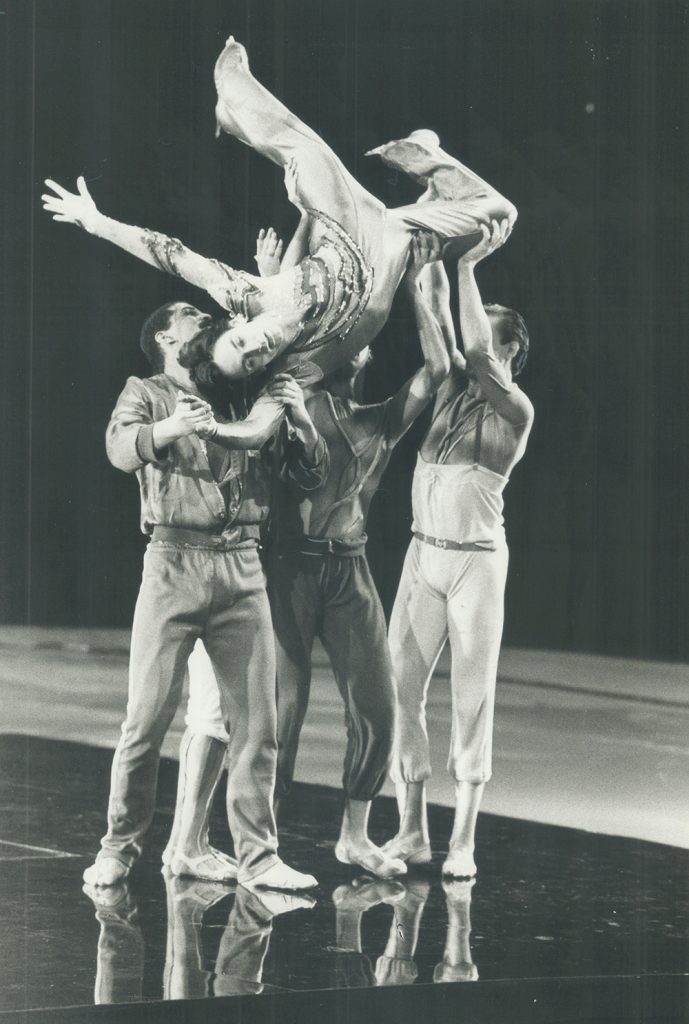

Toller Cranston rehearsing with dancers for Magic Planet, which aired on CTV, 1983. © Keith Beaty/Toronto Star via Getty Images

A new artistic style blossomed in Canada during this period, revolutionizing the sport. Coaches and choreographers brought artistry to the forefront as Canadian skater Toller Cranston brought musical interpretation to a groundbreaking new level. He was known as “Nijinsky on Ice.”

Theatre on Ice classes became part of training. Figure skating became more lyrical and imaginative.

For spectators, new technology also changed the sport. Audiences could now watch colour television coverage of skating competitions, increasing figure skating’s popularity as a spectator sport. Free skating programs were the highlight for the audience. In the 1970s, the International Skating Union lowered the value of figures and added a short program.

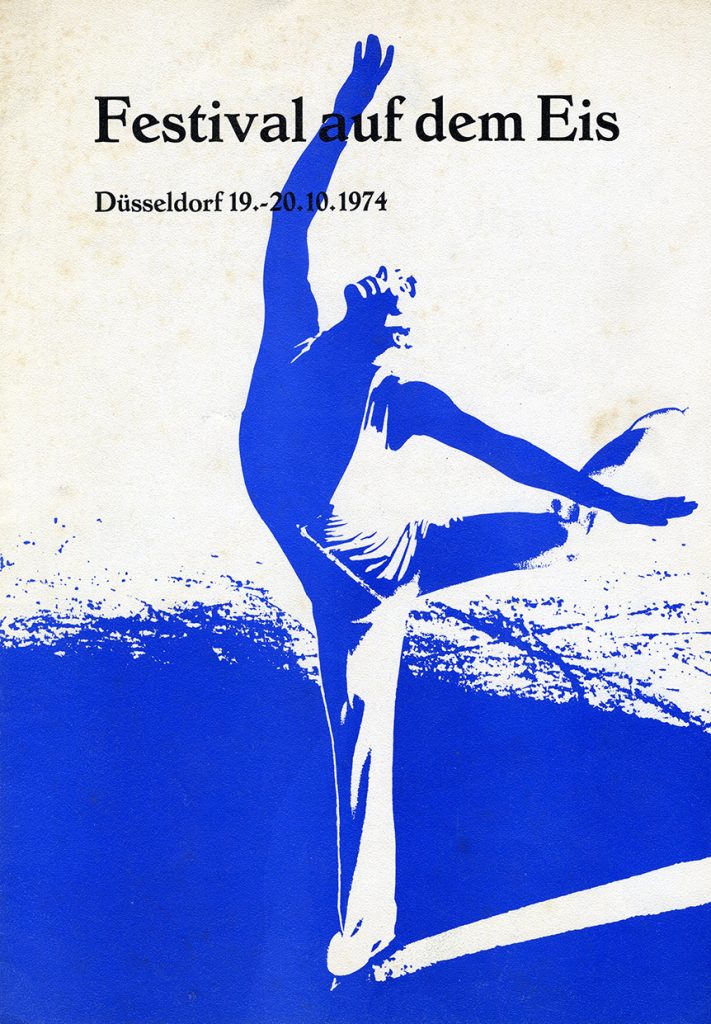

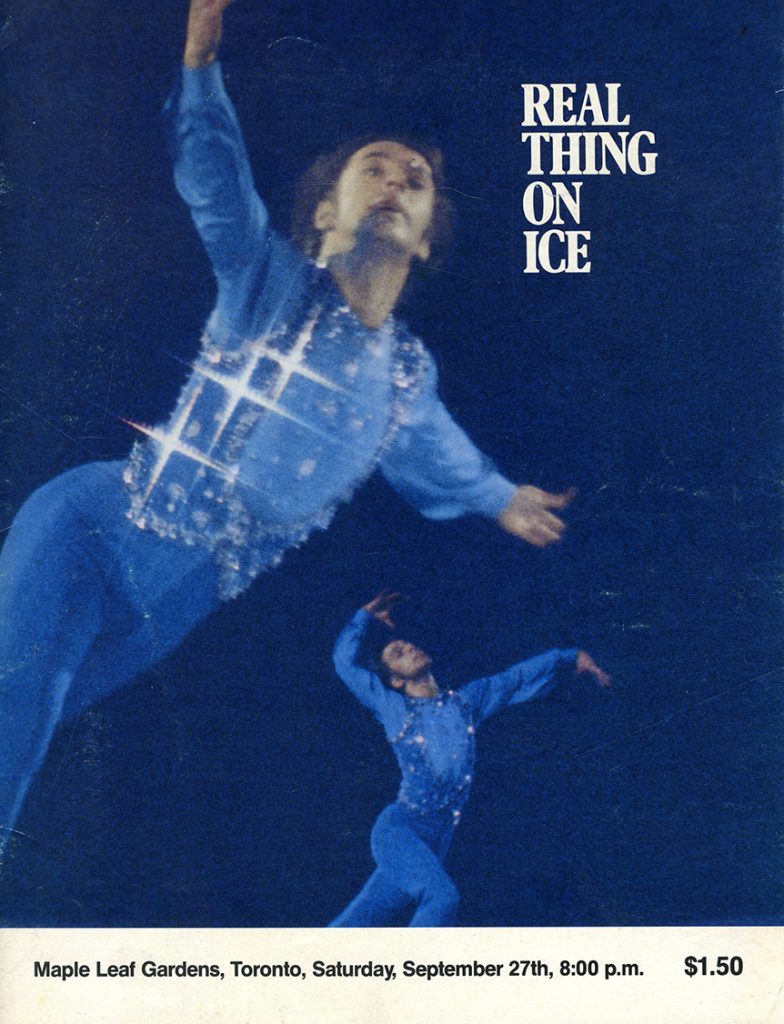

Televised weekly skating shows and skating specials replaced large skating carnivals. Many champion skaters travelled the globe by taking part in live tours.

CANADIAN GOLD CHAMPIONS ON THE WORLD STAGE!

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

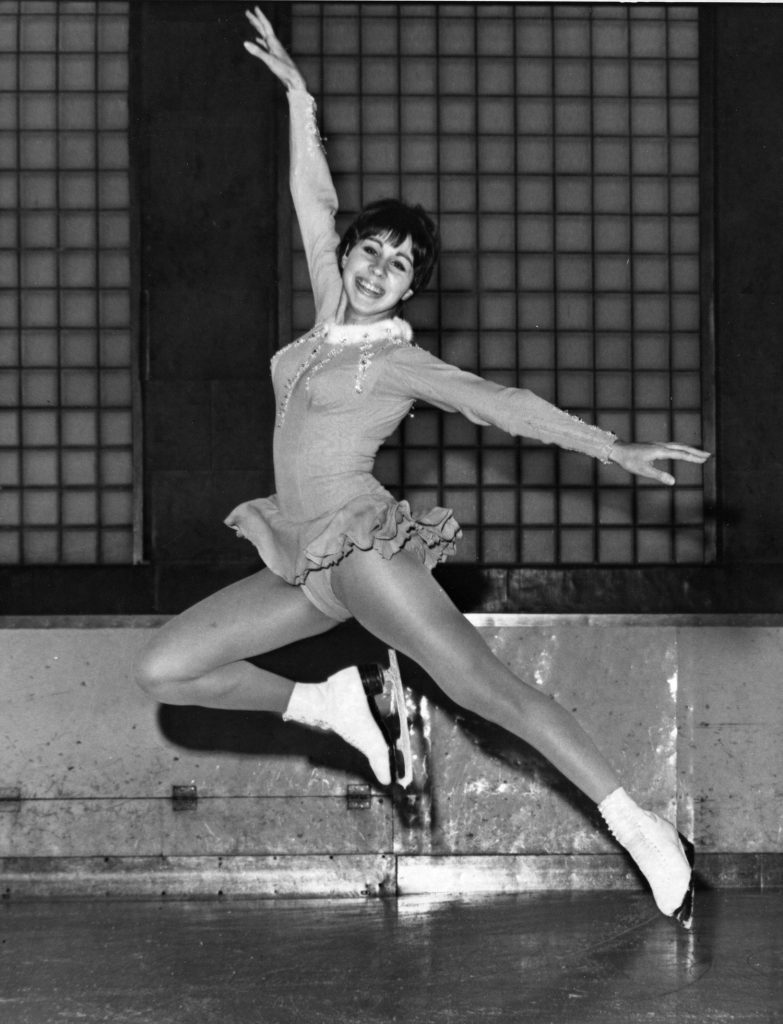

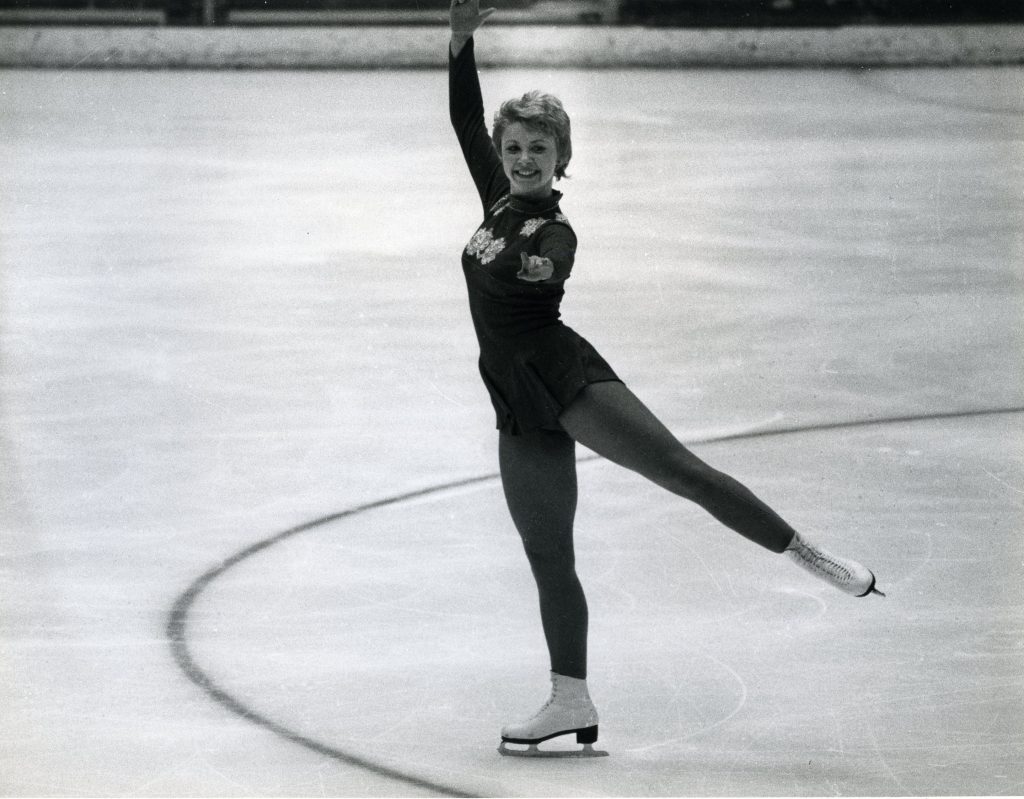

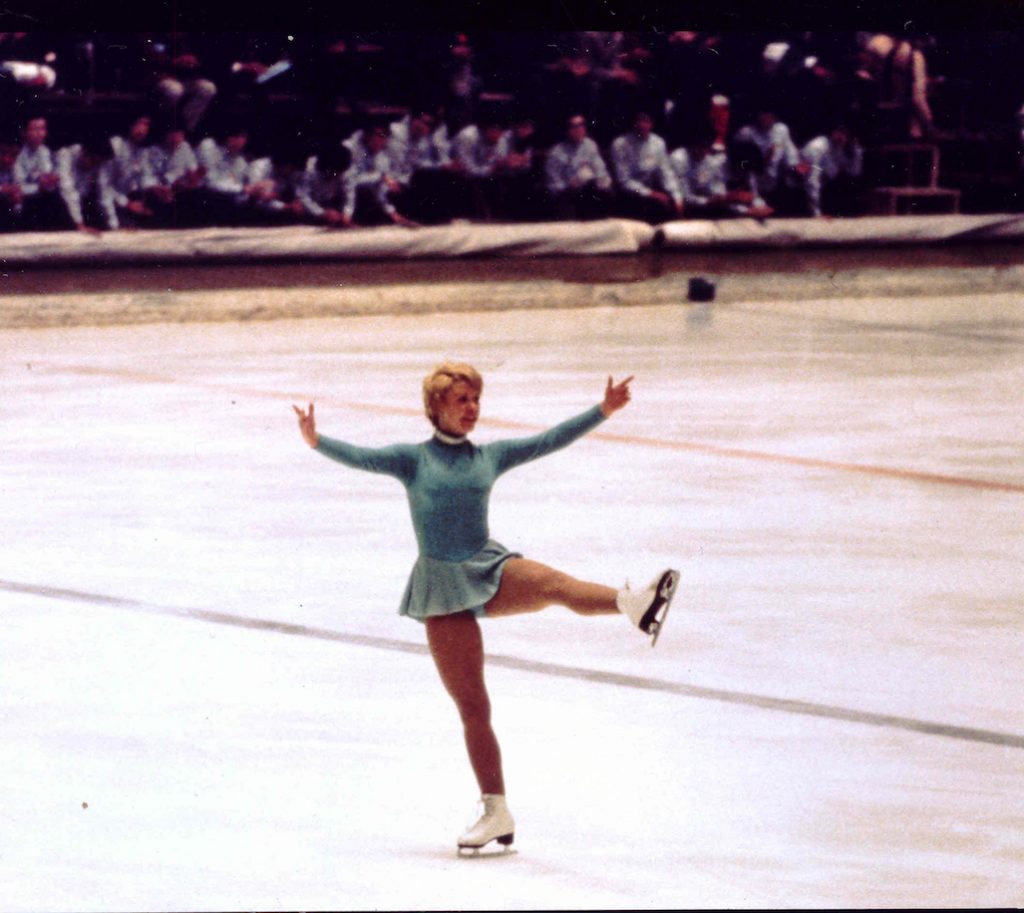

Petra Burka skating at the World Championships, Colorado Springs, 1965. © Skate Canada

Petra Burka, wearing a long-sleeved costume, skates around the ice.

She gracefully lands various jumps with ballet arms incorporated into the two double rotation jumps.

Transcript:

[Music: Tchaikovsky and Beethoven, soft, slow orchestra music]

A double axel but watch the arms. That shows complete control to be able to vary the arms like that.

[applause]

Here comes a similar variation and a double lutz jump coming up. Once again, watch the arms and the height of the jump.

[applause]

Karen Magnussen, World Champion 1973

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Karen Magnussen skating at the World Championships, Bratislava, 1973. © Skate Canada

Karen Magnussen, in a peach/pink-coloured long sleeve costume, performs a camel spin and a layback spin with a jump in between, while an audience watches in the background.

Transcript:

[Music: slow orchestra music]

[applause]

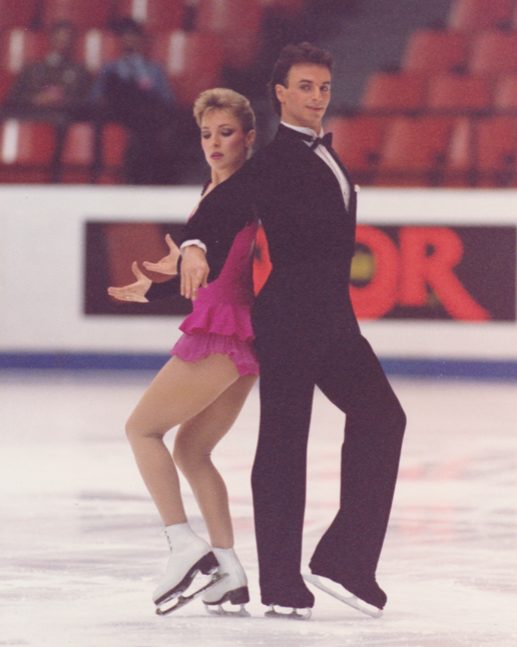

Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini, Pairs, World Champions 1984

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini skating at the World Championships, Ottawa, 1984. © Skate Canada

Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini, pair skaters, in bright blue costumes, perform a deep inside edge death spiral, a series of spinning overhead lifts and finish with a throw twist from a lift.

The arena is filled with spectators, flags from various nations, and advertisements.

Transcript:

[Music: “Concerto in F Major: I. Allegro” by Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra & Leonard Slatkin & Jeffrey Siegel]

[applause throughout]

[muffled] Better!

Like this, and she’s right back in the audience. Sandra screaming no.

They’ve only got thirty seconds left to go, good overhead lift, again with the variation, nice position in the air.

They look happy, they know that they’ve skated well, this could be it.

Who won the men’s gold medal for the free skating segment, but not the overall Worlds competition?

Who won the men’s gold medal for the free skating segment, but not the overall Worlds competition?

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Toller Cranston skating at the Canadian Championships, Vancouver, 1973. © Skate Canada

Toller Cranston won the free skating segment in both 1972 and 1974.

Boots & Blades

Knebli Boots Go International

Knebli’s business took off during this period. Having launched into boot making in 1948, during this period the company had an international clientele made up of Canadian, American, British, European, and Japanese champions. Still constructing each pair by hand to the custom measurements of each client, John Knebli and Elizabeth Knebli, his business partner and wife, supplied the sport’s highest-level champions during this period. Champions such as Karen Magnussen, Sandra Bezic, Val Bezic, Barbara Wagner, Bob Paul, Paulette Doan, Ken Ormsby, Petra Burka, Don Jackson, Toller Cranston, Vern Taylor, Brian Orser, Barbara Underhill, Paul Martini, and international skaters such as Kyoko Sato (Japan) wore custom Knebli boots.

Knebli advertisement in The Toronto Cricket Skating & Curling Cub program “Then and Now”, 1967. Astra Burka Archives

What was the name of the first Canadian TV variety show featuring skaters?

What was the name of the first Canadian TV variety show featuring skaters?

Stars on Ice ran from 1976 to 1981 on CTV. Alex Trebek hosted it.

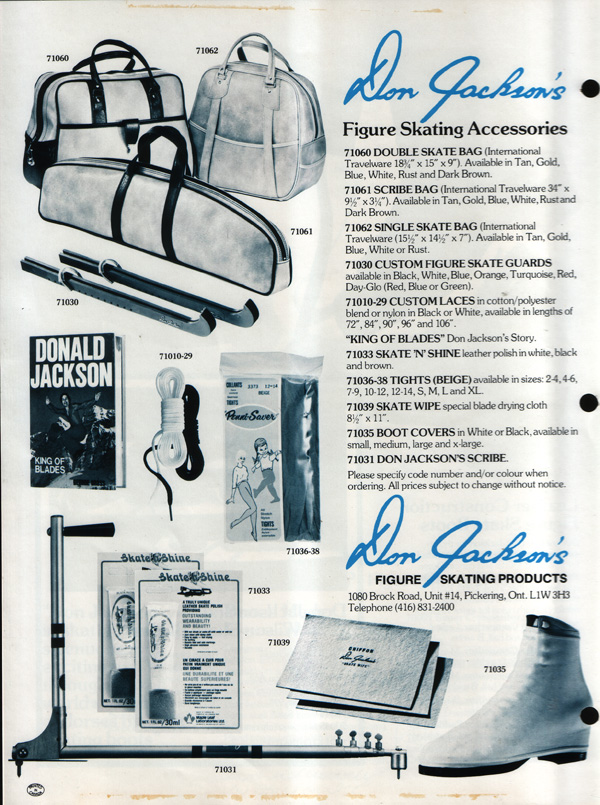

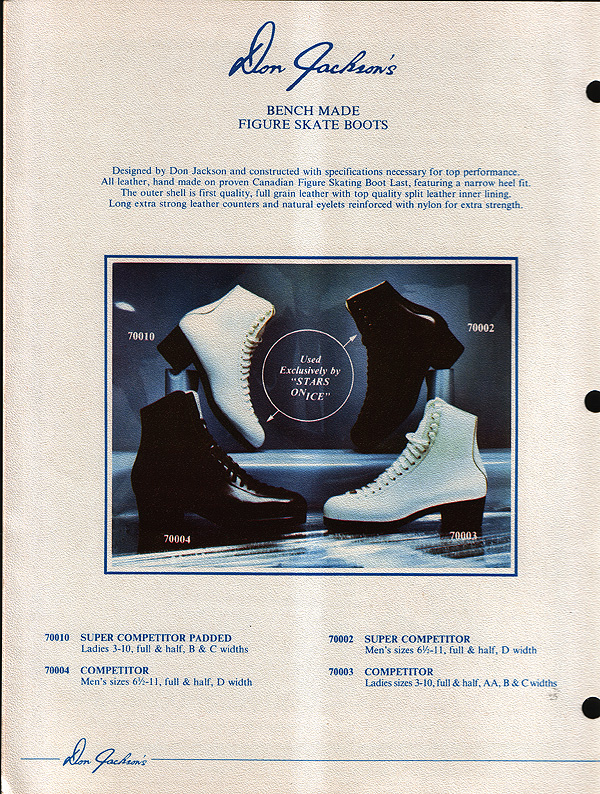

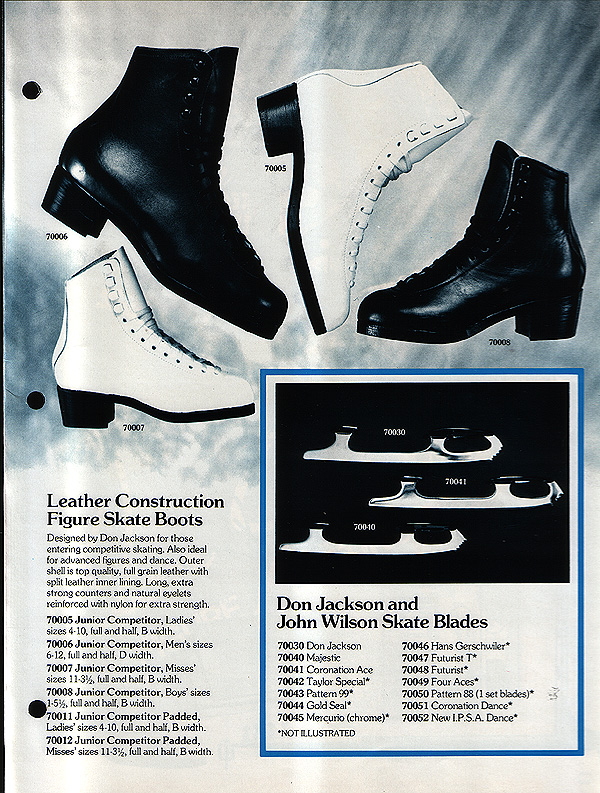

Don Jackson’s Figure Skating Products

Don Jackson, 1962 World champion, started a mass-market skate boot business in Ontario. The business idea was sparked with the help of Max Gould, a leisure skater and accountant for the Bata Corporation’s then Canadian headquarters at the Bata shoe factory in Batawa, Ontario. Don established Don Jackson Skate Products with his brother, Bill, in 1966.

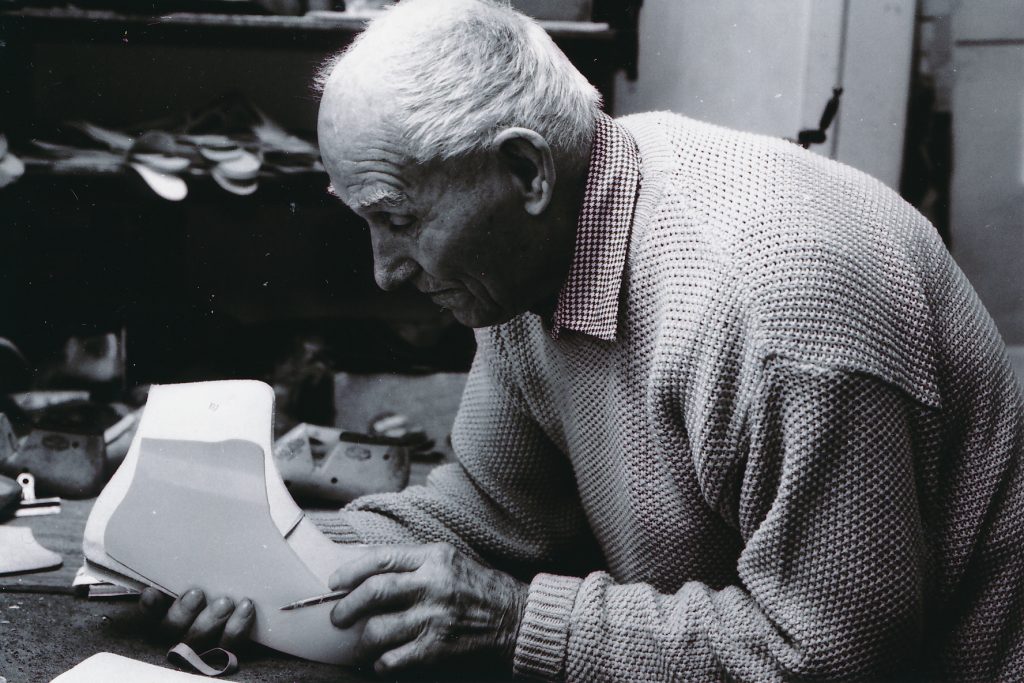

Don Jackson inspecting skate boots being made in Skutec factory, Czechoslovakia, c. 1983. © Canada Sports Hall of Fame (Photo Lubomir Duchoslav)

Anthony Ronza, shoe designer and creator of the popular Cougar brand of shoes, suggested in the early 1970s that Jackson import boots from Europe for reliable quality and supply. Jackson found a factory in Skutec, Czechoslovakia that could manufacture skate boots made-to-order. In time, Jackson’s company diversified to offer four models of boots for skaters of varying abilities (from beginner to elite). Depending on the model, blades by either CCM or John Wilson were mounted on the boots.

The Jacksons had a partnership with Don Bauer, the son of the founder of the Bauer Skate Company of Canada. Kim Bauer (Don’s Bauer’s son) and Wayne Schagena, founders of Tournament Sports, eventually bought Don Jackson Skate Products in 1986. All of the following Don Jackson’s Skating Products images are courtesy of Donald Jackson and William Jackson:

“Super Competitor” skate boots for men and women. Courtesy of Donald Jackson and William Jackson

Other Boot and Blade Makers

Cambridge, Ontario, local Ed Rose, like Knebli, was a custom boot maker who started his career making orthopedic footwear. Rose made boots for some of the top skaters of the Preston Figure Skating Club, in consultation with Canadian Olympic coach Kerry Leitch.

Charlene Jordan’s skating boots custom made by Ed Rose, c. 1993. Courtesy of Charlene Jordan

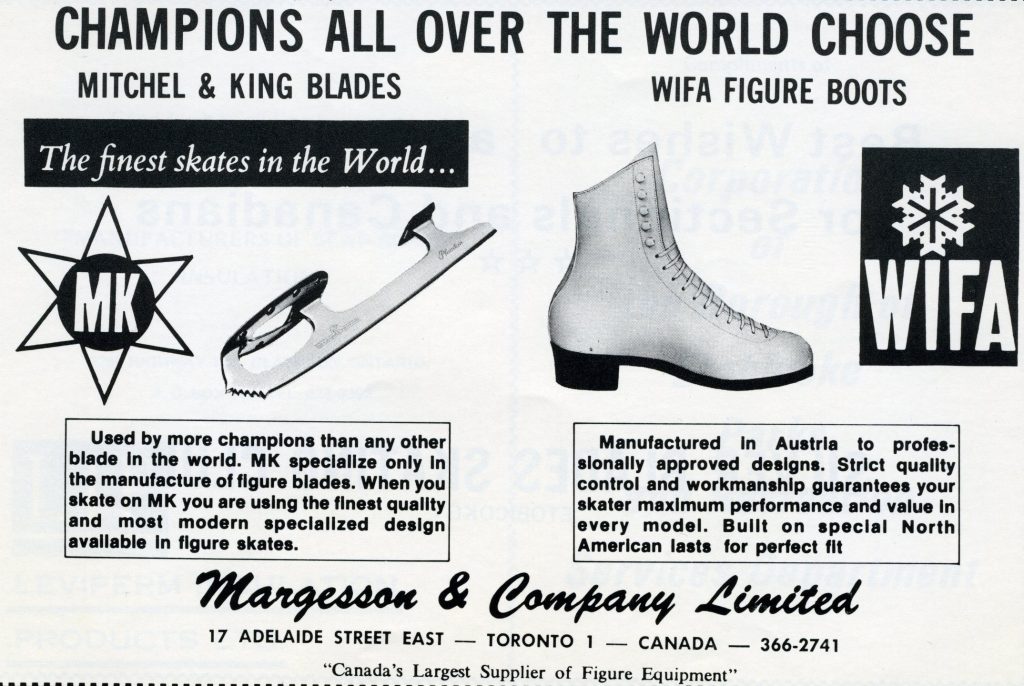

Other options for skaters included American companies such as Harlick, and Riedell. The Vienna-based boot brand WIFA was another popular choice.

Austrian WIFA boots and British MK blades advertisement, in the 1973 Central Ontario Sectional Championships program. Astra Burka Archives

Barbara Underhill’s WIFA Boots. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Paul Martini’s WIFA Boots and John Wilson Gold Seal Blades. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Blades specific to ice dancing were developed. Dance blades were cut shorter at the heel so that skaters’ blades did not entangle as they skated. Dancers could choose from Jackson Dance, Riedell Dance, John Wilson Coronation Dance, and MK Dance blades.

Lucinda Zak’s leisure skates worn on outdoor rinks in Edmonton, 1969. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S12.5

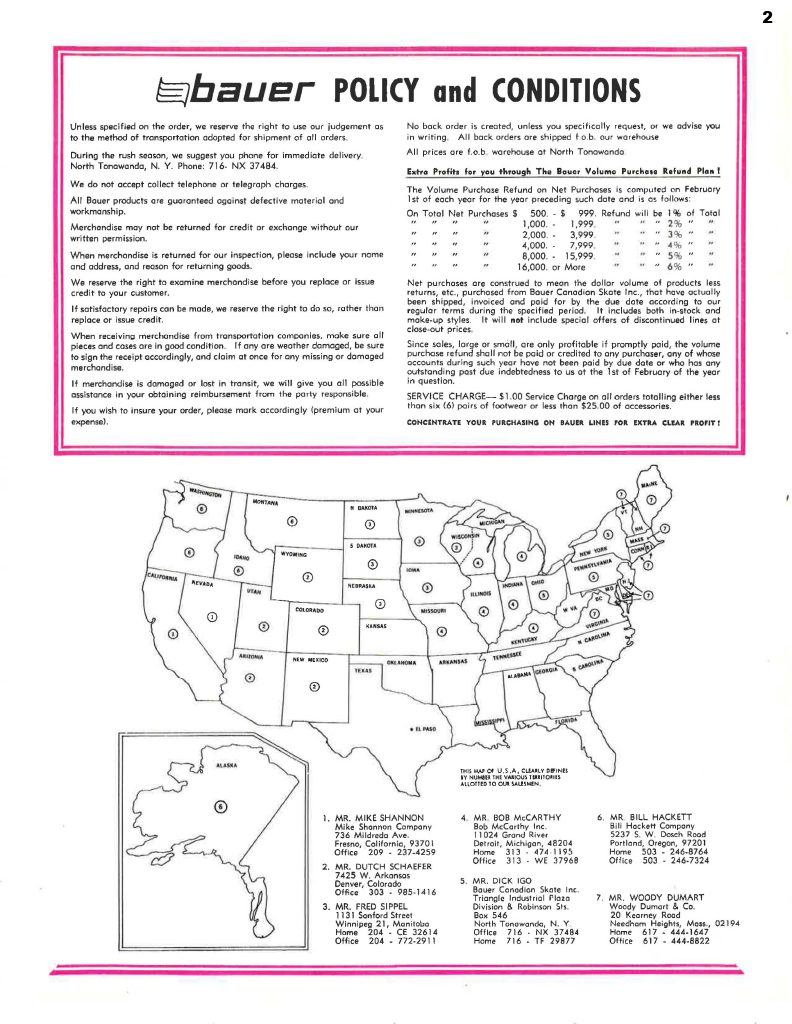

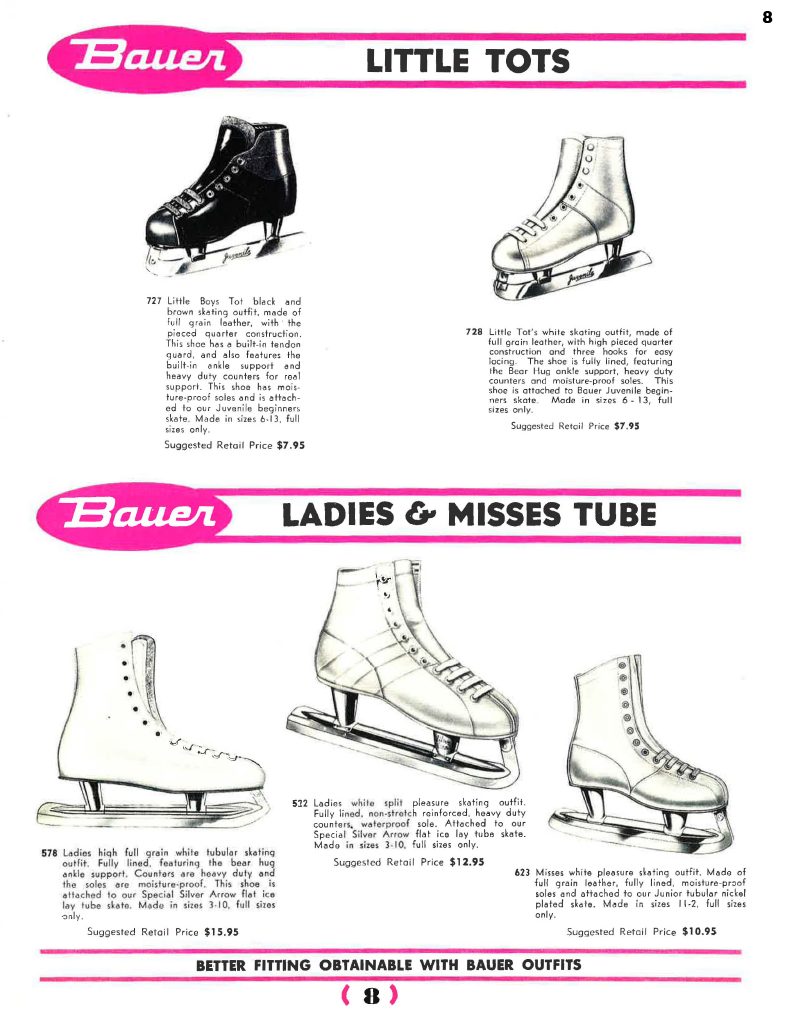

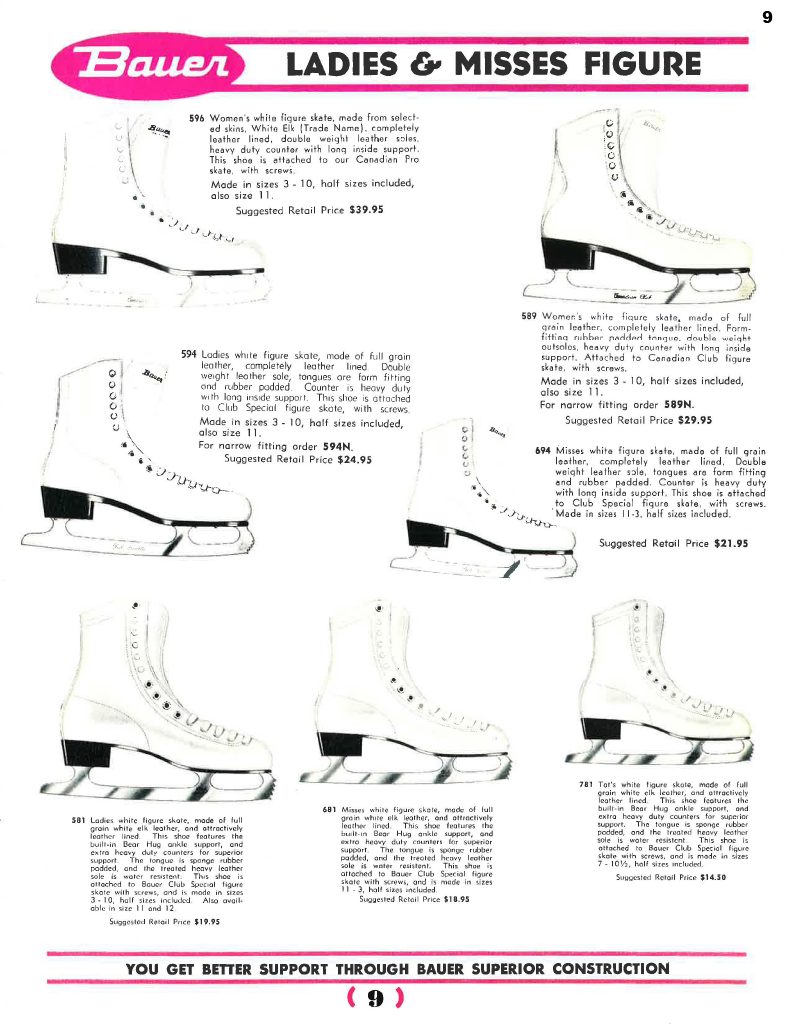

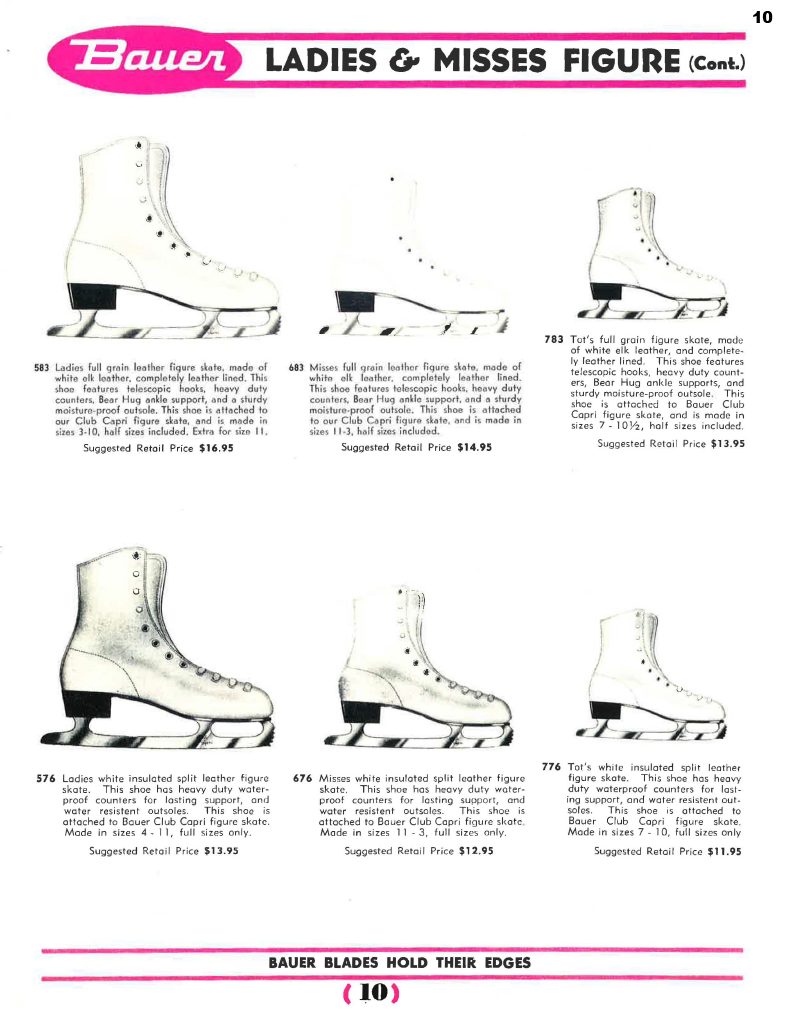

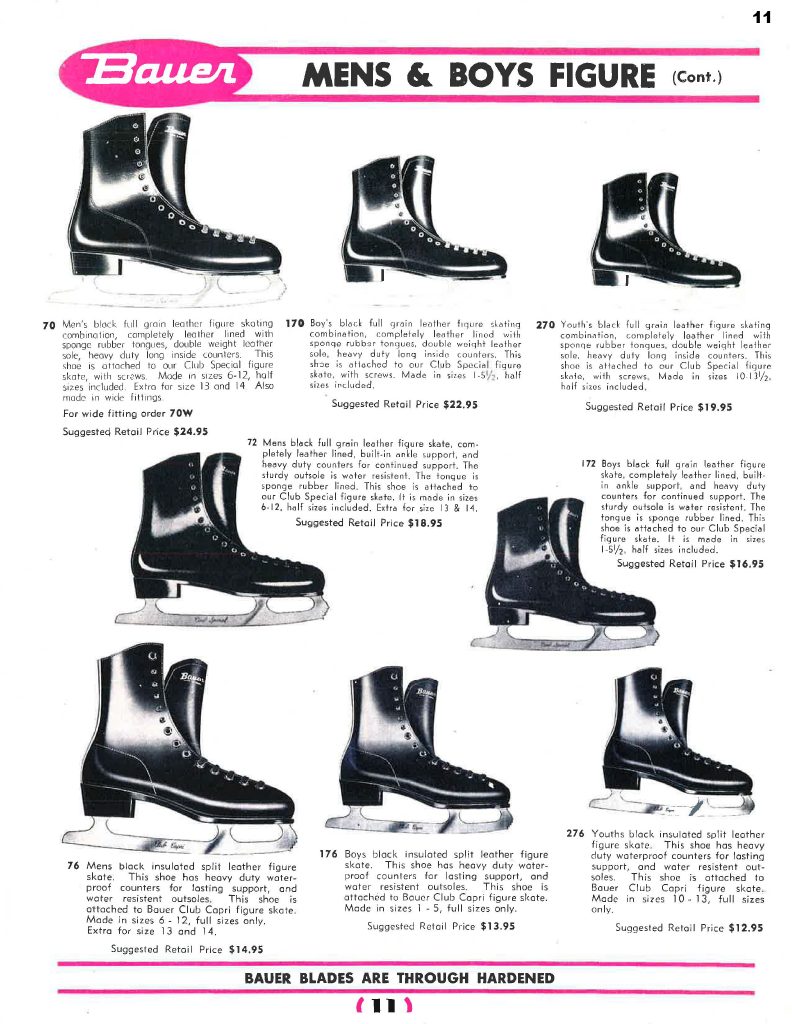

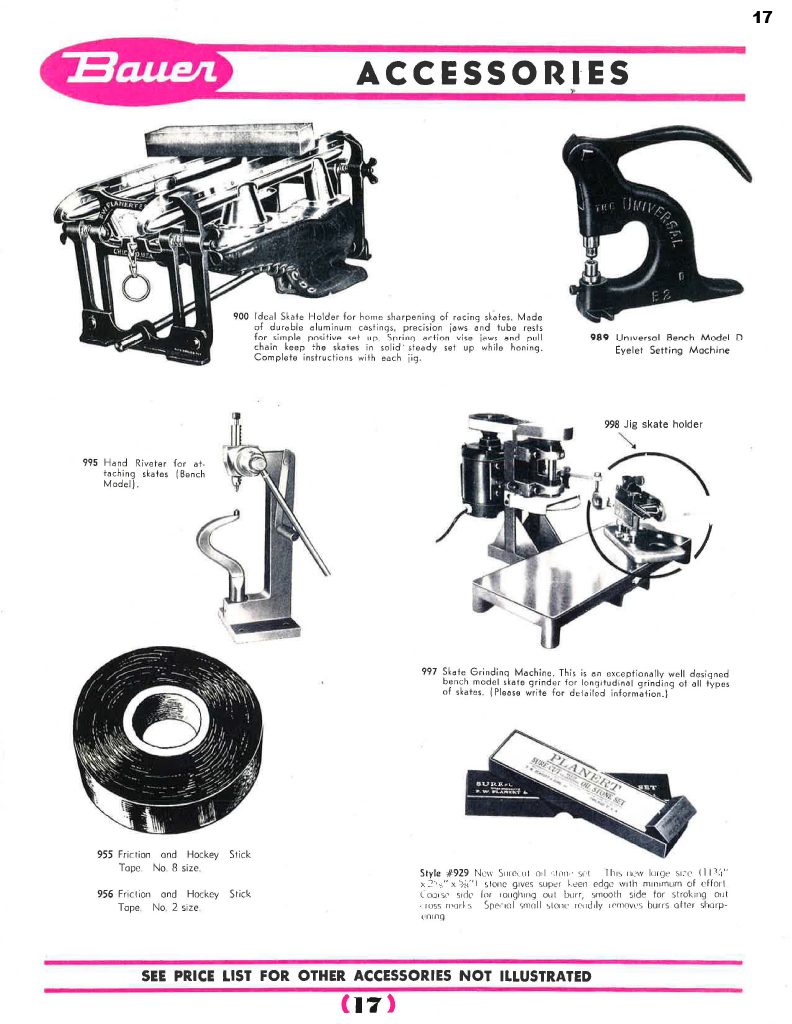

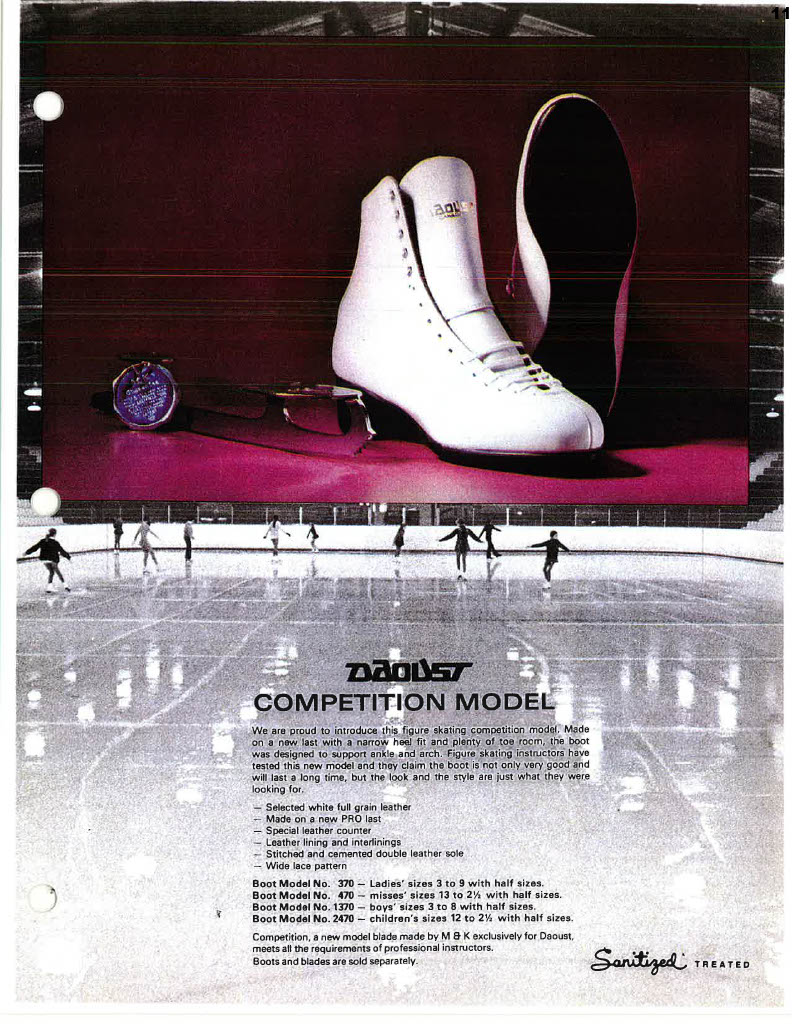

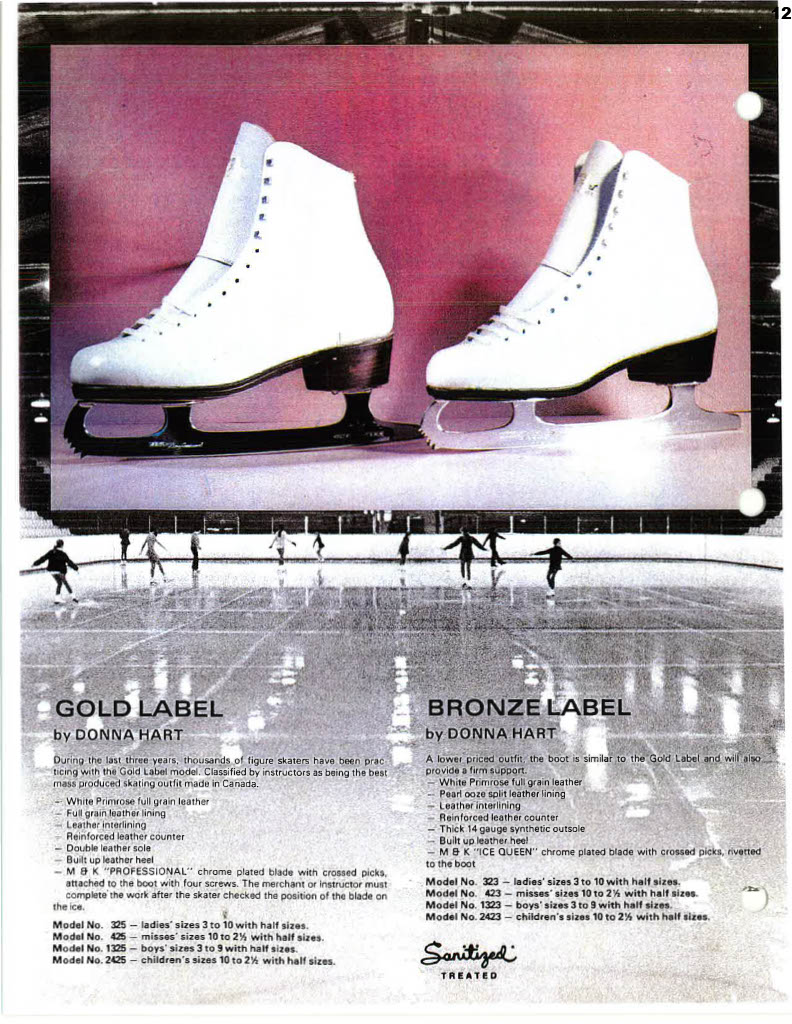

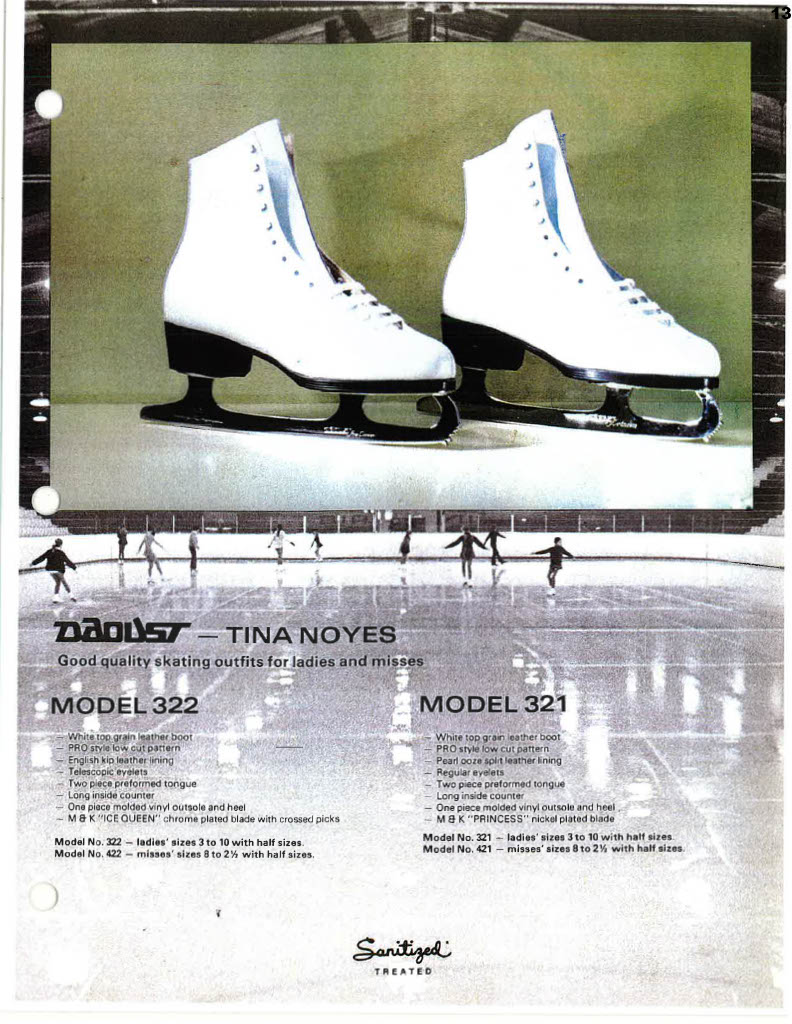

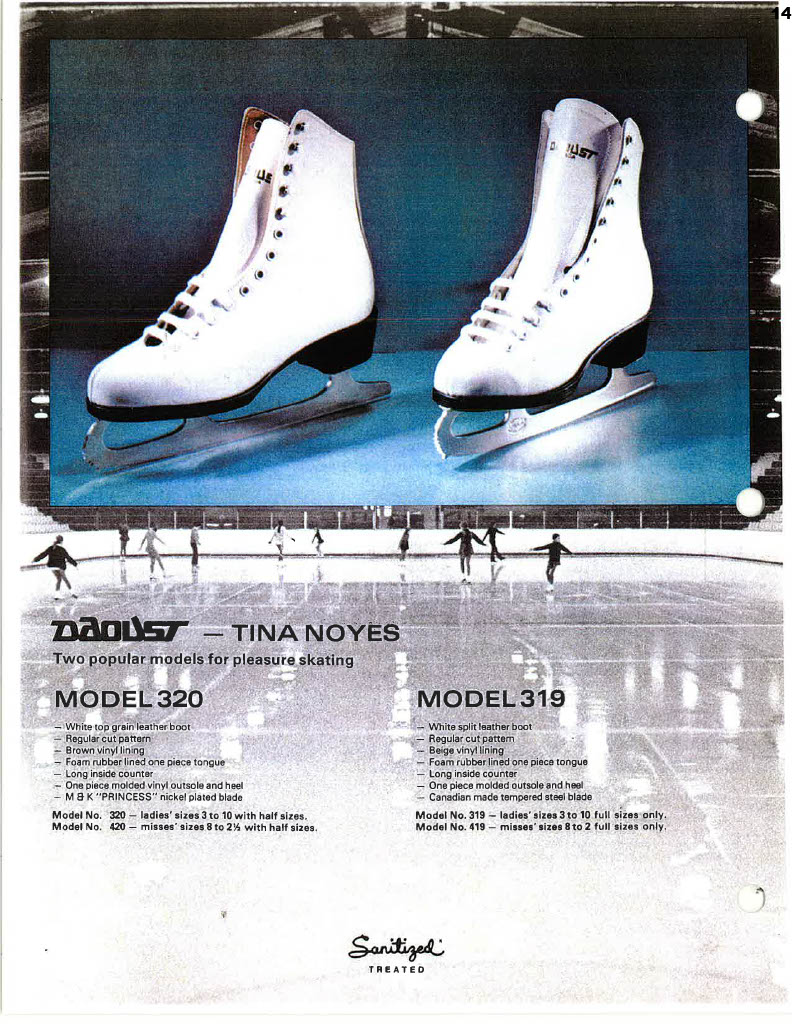

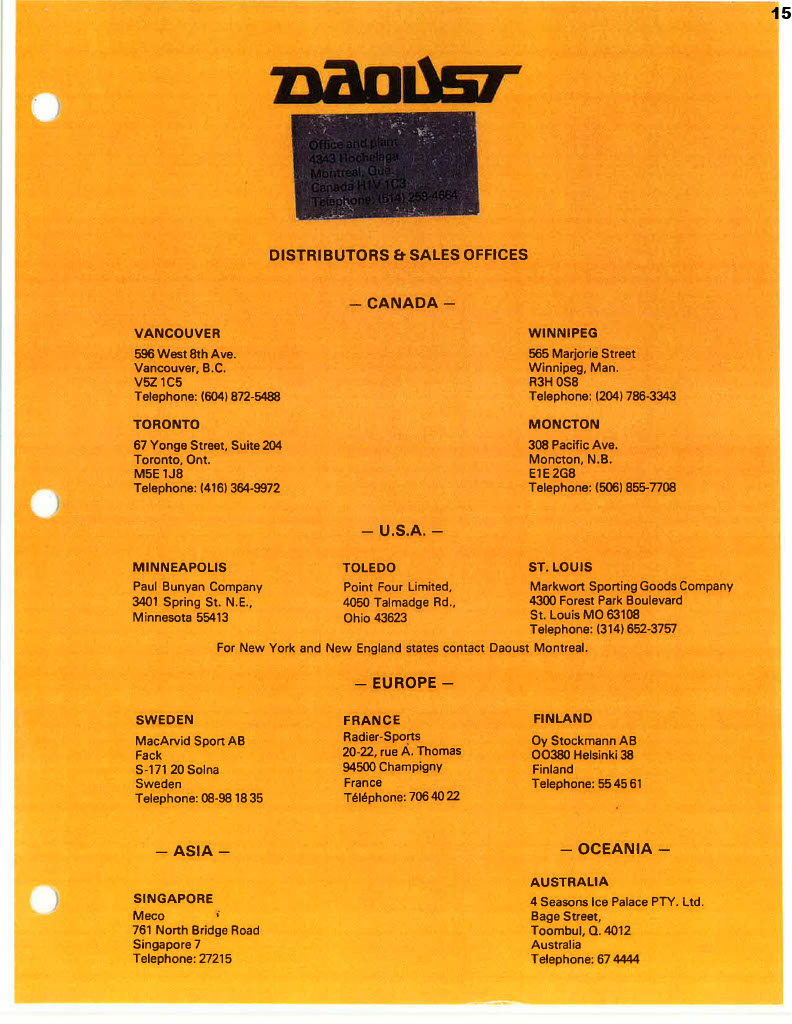

CCM, Daoust, and Bauer were the largest skate makers in Canada at this time. Besides their higher-end models, they sold more affordable, mass-produced boot and blade sets for the general public. These were a popular option for the recreational skater, and were known worldwide.

Movement

The Rules Change

Media coverage of skating influenced its development. Figures lost their novelty. On television, figures did not have the same audience appeal as expressive free skating programs, so to appeal to the audience watching on television, the ISU introduced another free skating component and reduced the focus on figures.

Pairs and ice dancing followed the same trend.

Women

Audiences loved American skaters Peggy Fleming, Janet Lynn, and Dorothy Hamill. Like Canada’s Karen Magnussen, these athletes displayed their artistry and grace on the ice as well as their technique. Janet Lynn’s lyrical, expressive free skating performances particularly captivated audiences everywhere.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Janet Lynn skating at the World Championships, Ljubljana, 1970. © Skate Canada

A. Figures and Free Skating

Karen Magnussen in a skating pose at the Sapporo Winter Olympics, 1972. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

In 1967 the ISU reduced the figure component from 60% to 50% of a skater’s final mark. In 1973, the number of required figures was reduced from six to three, and a short program was introduced. The program accounted for 20% of a skater’s mark, with figures reduced to 40% and the long program at 40%.

Male skaters routinely performed triple jumps. Women started to experiment with triple jumps. Artistic choreography and more expressive musical interpretation linked the technical elements (jumps, spins and footwork) together.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Karen Magnussen doing figures at the Canadian Championships, Vancouver, 1973. © Skate Canada

A man in a black suit and bow tie fills the frame, explaining the scoring system while as Karen Magnussen waits on the ice surface behind him.

The man leaves, and she begins skating in a figure-eight front of the judges.

The camera zooms in on her feet during this routine.

Petra Burka and Donald Jackson comment on the figure tracing work Karen is so carefully executing on the clean ice.

She is performing the outside forward double-three-turn figure eight.

Transcript:

Figures count for forty percent of the overall marks in senior’s competition. There’s always been the argument that figures count too much in the overall score, but they are necessary to develop the technique and discipline to become a champion. Petra Burka and Donald Jackson look back as Karen Magnussen and Toller Cranston go through their figures.

It’s really strange because when you get out there in front of the judges like this, you could be practicing eight hours every day but it’s just a completely different feeling, you know, you’re out there on clean ice, you’re by yourself. It’s a very strange experience.

[Music: “Serenade to Summertime” by Paul Mauriat]

Yes, I remember on this double three, Karen here is skating this in front of the judges so the pressure is on her, but the most difficult part is right here in between the threes…

Oh, that’s called a blind spot.

And you’re turning your head and you just don’t know where you are, so you have to really do this figure by feel and that takes years of practice, I’d say ten years at least to really get the feeling of tracing.

Yep. Tracing means getting those lines on top of each other, notice Karen’s blade goes right onto that line again. You have to make circles too, I was very good at making squares. Also, those turns have to be opposite to each other, you’ll notice Karen will do a turn here, it’s one third of the way around and then she’ll come around --here’s that blind spot where she turns her head-- and then another turn, opposite.

She has to trace this six times --we have three pushes on each foot – that’s why we have six point zero as a perfect mark because for each push off they get a point and because there’s six pushes in this, and six points. A lot of people probably wonder why we don’t mark out of ten, but that’s the reason.

B. Pair Skating

Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini performing a skating move at the World Championships, Ottawa, 1984. © Skate Canada

Pair skating elements became more challenging. Single jump throw lifts became double throw lifts. Skaters were expected to perform required technical elements in the new two and a half-minute short program. This made up one-third of the team’s score. They used the long program to show off more of their best moves, interpret the music, and to show their strength and endurance.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini skating at the Canadian Championships, Thunder Bay, 1979. © Skate Canada

Pair skaters Underhill and Martini, wearing matching black costumes, perform a routine in unison, including a side-by-side double toe loop jump, and a throw double lutz.

They finish their routine with a low pair spin.

Transcript:

[Music: upbeat orchestra music]

They’re jamming a lot more to those pairs programs than they used to, Otto.

[applause throughout]

There’s no question about that John, and five minutes is a long time, and they haven’t slowed down for one second of it through this grueling five-minute performance.

Barb Underhill and Paul Martini.

Pairs

Russian pair skaters Irina Rodnina and Alexander Zaitsev were powerfully athletic. Rodnina, who originally was paired with Alexei Ulanov, is the only female pair skater to win 10 successive World Championships.

Russians dominated the pairs category in this period, winning 17 of 20 world championships. In 1984, Canada’s Underhill and Martini were World Pairs champions, unseating the Russian’s once in during this 20-year stretch.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Irina Rodnina and Alexander Zaitsev skating at the World Championships, Gothenburg, 1976. © Skate Canada

C. Ice Dancing

Tracy Wilson and Robert McCall in a dance pose. © Skate Canada

Before 1967 compulsory dances accounted for 60% of a couple’s mark, with 40% dedicated to the free dance. After 1967, the free dance was increased to 50% of the couple’s mark.

Ice dancers were restricted in terms of arm movements and lifts. Performances resembled ballroom dance on ice. By introducing the original dance, the category became more interpretive.

An “original set pattern dance,” which later became known as the “original dance,” replaced one of the compulsory dances. The original dance is a unique program created by each competing team. The style would be designated a year before the competition by the ISU; designations would be a type of dancing, for example tango, rumba, or waltz. Each team selected their own music and choreography, creating an interpretive dance became part of the couple’s a skater’s competitive routine.

Russian and British skaters dominated in this category. Not one Canadian ice dancing pair medalled internationally during this 20-year period until Tracy Wilson and Robert McCall broke the spell with a bronze medal in 1986 at the World Figure Skating Championships in Geneva.

Ice dancing became an official category in the Olympics in 1976.

Ice Dancing : Pakhomova/Gorshkov

Like in the pairs category, Russian skaters also reigned supreme in ice dancing. They pushed the boundaries of what ice dancing could be. They had artistry, musical interpretation and technical skill. Lyudmila Pakhomova and Alexandr Gorshkov suffused their performances with balletic grace. Irina Moiseeva and Andrei Minenkov wowed audiences with their expressive musical interpretation.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Ludmilla Pakhomova and Alexander Gorshkov skating at the World Championships, Bratislava, 1973. © Skate Canada

Ice Dancing : Torvill/Dean

British champions Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean were exceptional performers. When they skated to Maurice Ravel’s Bolero at the 1984 Olympics, it electrified the audience. Their holistic performance combined musical interpretation with art and technical skill.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean skating at the World Championships, Ottawa, 1984. © Skate Canada

Who was the first Canadian skater to land a triple axel?

Who was the first Canadian skater to land a triple axel?

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Vern Taylor landing the first triple axel at the World Championships, Ottawa, 1978. © Skate Canada

Vern Taylor landed the jump in 1978.

Theatre on Ice

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Ellen Burka describing her Theatre on Ice training for skaters. © Skate to Survive 2007, directed by Astra Burka, produced by Astra Burka and Michael Kainer.

Photographs of a young Ellen Burka in dancing poses appear on the screen.

Ellen Burka, seated on a chair in a garden is being interviewed and explains how she created Theatre On Ice.

After, a group of young figure skaters dressed in black leggings and leotards, interpret, and perform theatrical movements on ice.

Transcript:

[soft instrumental music]

I was very fortunate that I took lessons from a German, young dancer. And from her, I really learned expressive dancing. Being a dancer, and also of course coaching figure skating, I said there’s a connection between dance and figure skating and why can’t we figure skaters not move the same way as dancers?

So, in the early fifties I started Theatre on Ice. Then I said to the kids, here’s your music, interpret the music and try to imagine what that is. And I’ve been doing that all until now and I still do Theatre on Ice classes.

Dutch champion and Canadian coach Ellen Burka was always interested in choreography. To expand knowledge to the skaters, she created Theatre on Ice classes for her students at the Toronto Skating Club in 1973. These classes introduced skaters to different artistic practices. Skaters learned classical ballet, modern, and jazz dance technique. They incorporated dramatic elements from miming and acting into their routines. Burka instructed her students to “listen to the music, think what you feel, and try and interpret it on the ice.”

Burka pushed the boundaries of artistic and musical interpretation throughout her career. In the 1950s, she produced Georges Bizet’s Carmen on ice at the Lakeshore Arena. The lively performance included traditional Spanish dancers, dancing on a platform stage. In 1978, she was the first figure skating coach to receive the Order of Canada. She received the honour “for elevating skating to an art form and for imaginative choreography on the ice.”

Ellen Burka and her student Toller Cranston were innovators. They brought a new artistic style of skating to the ice.

Toller Cranston: A New Style is Born

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Ellen Burka describing Toller’s style of skating as he performs. © Skate to Survive 2007, directed by Astra Burka, produced by Astra Burka and Michael Kainer.

A group of young figure skaters, all in black, dance on the ice.

Coach Ellen Burka in a green blouse sits on a chair in an outdoor garden. She explains that male skaters did not dare to raise their arms higher than their shoulders in the sixties and early seventies.

A spotlight highlights male figure skater Toller Cranston as he performs on ice innovative skating movements to music with stretched arms above his shoulders.

Transcript:

[soft instrumental music]

So, in the early fifties I started Theatre on Ice. Then I said to the kids, here’s your music, interpret the music and try to imagine what that is. And I’ve been doing that all until now and I still do Theatre on Ice classes. And through this, through all these over-exaggerated movements which we developed during that, I developed a certain style, but I never had a student who could do that because people didn’t dare to raise their arms too high, a boy, even in the sixties, close to the seventies wouldn’t dare to lift his arms higher than his shoulders.

So then Toller arrived on the scene, and he was my tool. I said, look Toller, you’re so flexible, you’re so stretched, why don’t we go and bend our knees and do some interpretive movements in our skating, and he was not afraid to do that.

[soft instrumental music]]

Later when Toller became international, it was really taken over in Europe, all over the world, and a new style was born.

Men

John Curry, British World and Olympic champion, had a lyrical ballet skating style that contrasted with Toller Cranston’s avant-garde style. Curry commissioned routines for his professional ice show performances from top choreographers like Twyla Tharp, Sir Kenneth MacMillan, and Peter Martins.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

John Curry skating at the World Championships, Gothenburg, 1976. © Skate Canada

Sandra Bezic, famous Canadian pair skater, commentator and choreographer, remarked that “Toller brought colour to men’s skating.”

Together, Cranston and his coach Ellen Burka created an artistic athleticism. Under Burka’s direction, Cranston experimented with new spins, footwork, and jumps and joined these together through avant-garde movements reminiscent of 1930s skating styles. His signature moves included bent-knee leg extensions, expressive arm movements, high kicks and running across the ice on his toe picks.

Cranston cut a dashing if untraditional figure out on the ice. He wore his hair long and loose, moved his arms above his shoulders in poetic motion, and wore unconventional costumes. When he interpreted music from the opera Pagliacci, he dropped to the ice in a dramatic pose at the end. The audience was spellbound. Cranston’s approach opened doors for figure skaters who wanted to express themselves.

When did ice dancing become an official category in the Olympic Winter Games ?

When did ice dancing become an official category in the Olympic Winter Games ?

In 1976 at Innsbruck, Austria.

Coaches and Choreographers

It was common for coaches also to be choreographers, but more and more coaches that produced top international skaters started to work with choreographers to create better programs. For example, Linda Brauckmann, coach and choreographer for Karen Magnussen, also sent Karen to Ellen Burka for additional training in interpretation.

Later in this period, the specialized work of a choreographer was needed. Coaches would hire choreographers to come in. Dancer and choreographer Brian Foley, the founder of Performing Dance Arts in Ontario, choreographed skating programs for many Canadian champions including Toller Cranston.

Sandra Bezic, having finished her amateur skating career, choreographed programs for many fellow elite athletes at the Olympic and World level. For example, she choreographed routines for Canadian world pair champions Barbara Underhill and Paul Martini who were coached by Louis Stong. Further to this specialization, Marijane Stong (also a skating coach and part of the creative team) selected the look, costume, and music.

Coaches and choreographers were working closely together to create routines like never before!

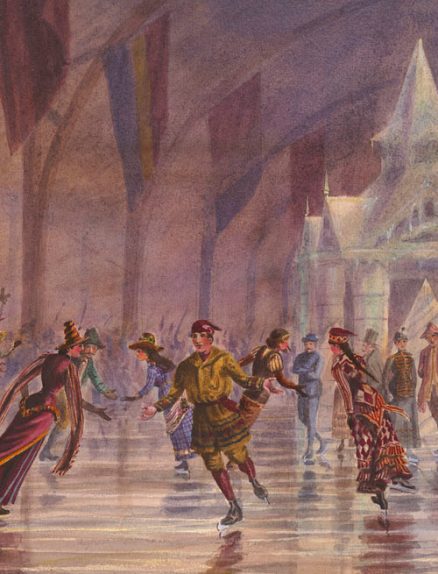

The Rise of Professional Ice Shows

Skating events were now broadcast live on television. The popularity of large carnivals waned. Local and regional skating clubs still produced smaller carnivals for their members.

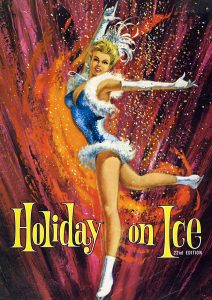

Program cover, Holiday on Ice, 1965. Astra Burka Archives

Program cover, Holiday on Ice, 1967-1968. Astra Burka Archives

Professional ice shows, however, were still popular entertainment. The CTV weekly show Stars on Ice (1976-1981) built a dedicated figure skating fan base. The CBC produced many figure skating television specials featuring Toller Cranston. He dazzled audiences with his dreamlike and extravagant shows Strawberry Ice, Magic Planet, and Dream Weaver.

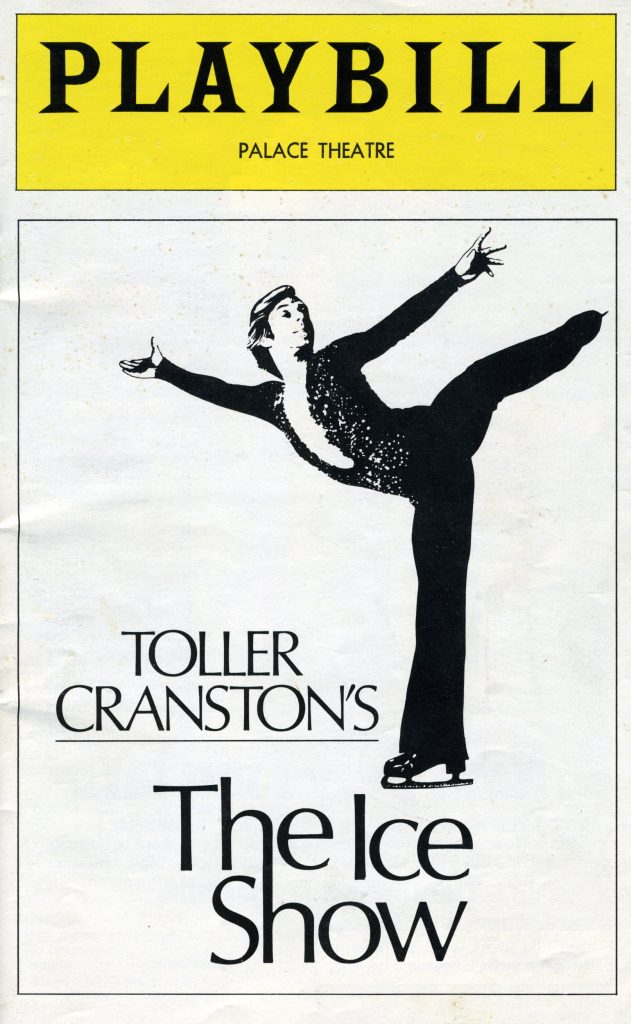

Toller Cranston’s “The Ice Show” at The Palace Theatre, NYC, 1977. Astra Burka Archives

Skaters toured the world in live shows. The Tour of World Figure Skating Champions, presented by Tom Collins, packed arenas across Europe and North America starting in 1969.

Costume

Stretch Fabrics

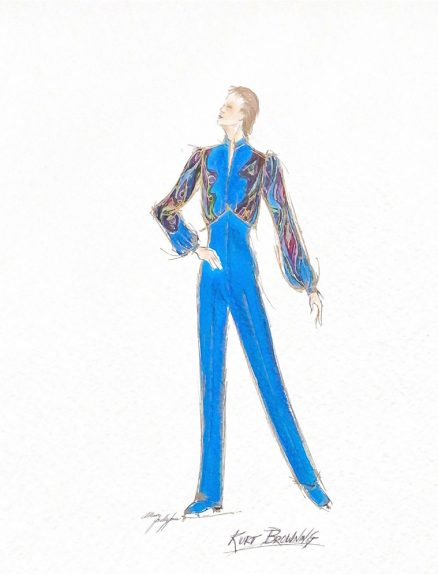

Stretch fabrics with four-way stretch made complex skating elements easier to perform. One-piece and two-piece outfits were worn by men. Toller Cranston was one of the first male skaters in Canada to wear two-piece stretch outfits, a Danskin top and a stretch pant. Renato La Selva, master tailor, designed and made costumes for Cranston. Cranston also had several costumes made by Malabar Ltd. in Toronto. For his CBC television specials, Frances Dafoe and Juul Haalmeyer designed his costumes.

For women, one-piece costumes were made with a stretchy fabric body, and a flowing chiffon skirt completed the look. These years saw big changes in how skaters dressed. Frances Dafoe, past champion, now designed costumes for female skaters; Margit Sandor, master seamstress, pattern-drafted and also constructed the costumes for top Canadian skaters including Petra Burka.

Costume became more important to the performance and it became more and more expensive to have custom-designed costumes for every performance. Skating mothers often sewed costumes for athletes they knew in addition to for their own children. Karen Magnussen benefited from this kind of generosity.

Karen Magnussen about to take a bow, 1972. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

The impact of this new material and increased focus on costumes was also positive for skaters’ appearance on colour television.

Music

Personality

In this period, skaters, coaches, and choreographers made more deliberate, individualized music choices. Burka’s Theatre on Ice classes emphasized storytelling through musical interpretation. Personal expression and storytelling was a foundational part of the ballet and modern dance classes skaters took.

Traditional programs for free skating started with fast-slow-fast tempos.

It was unusual for skaters to use one continuous piece of music for a skating program. Judges discouraged skaters from using one piece of music. In 1966, Petra Burka was told by the judges that she could not skate to Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty. Burka went back to her previous program. Karen Magnussen broke new ground in the early 1970s when she skated to a complete recording of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2. Soon, judges became more lenient, and it became more common for skaters to perform to one piece of music by a single composer.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean interpreting Ravel’s “Bolero”, World Championships, Ottawa, 1984. © Skate Canada

Pair of skaters, Torvill and Dean, in matching purple Greek-inspired costumes, interpret the music from Bolero and perform a series of lifts on the ground before standing up and skating in unison. The arena is filled with spectators.

Transcript:

Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean.

[Music: Maurice Ravel’s Bolero]

[applause]

Cassettes

Skaters continued to use custom-pressed vinyl records and reel-to-reel magnetic tapes into the 1970s.

Custom vinyl record of Lynn Nightingale’s “Compulsory Programme Practice ’72.” © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

Lynn Nightingale’s music on reel to reel, World championships, Tokyo, 1977. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

New music technology was being developed. In 1966 Canadian skaters in Peterborough were the first to use a cassette tape for an ice-dancing event. Cassette tapes were more affordable than vinyl records, and cassette tapes could be made and played more easily. Unfortunately, it was difficult to achieve the right speed and timing.

Announcer Wilf Langevin with Bill Dowding on the left. Music specialists. © Skate Canada

By the early 1970s, Wilf Langevin had solved this issue with fellow music technician Bill Dowding. Working with fellow Canadian audio technicians Jack Cohoe and Bill Taylor, the team created a device that attached to the cassette player, regulating the speed of the music. Synchronizing the sound and timing with this device was a way to solve the cassette tape challenge.

By the early 1980s, cassette tapes had completely replaced both vinyl records and reel-to-reel tapes in competitions.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

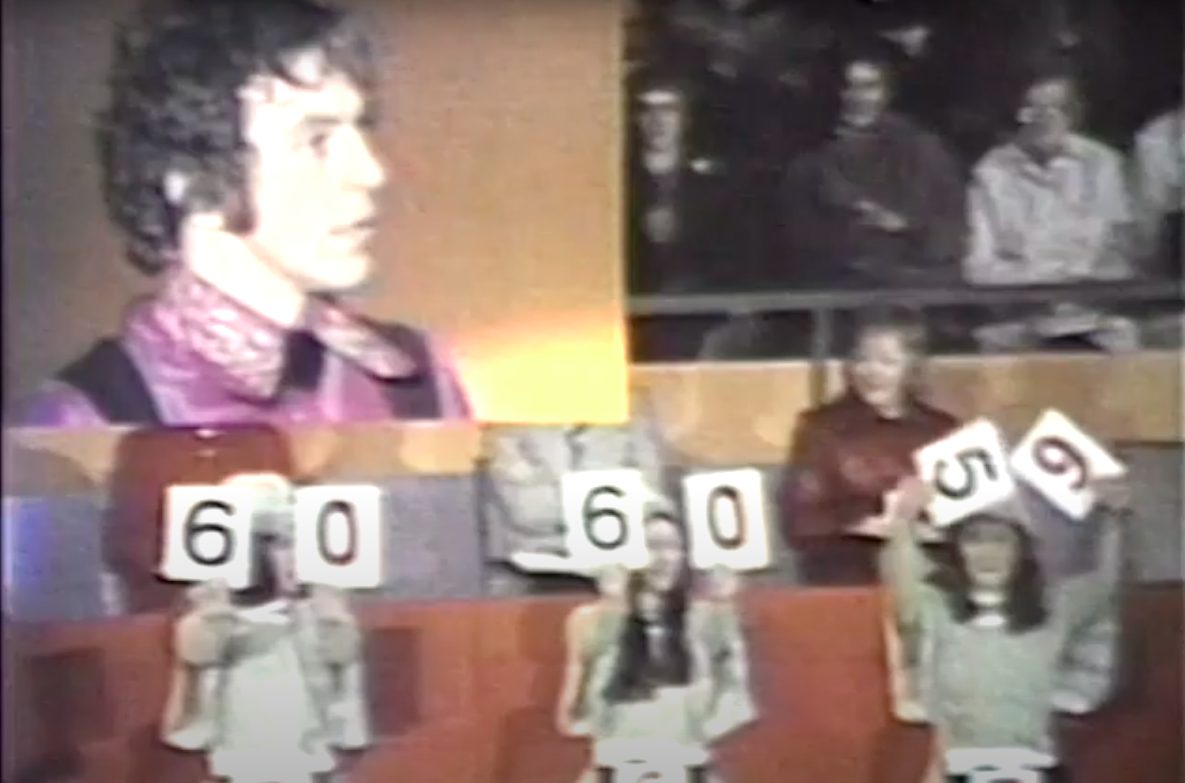

Wilf Langevin announcing Toller Cranston’s marks at the Canadian Championships, Vancouver, 1973. © Skate Canada

A male figure skater, Toller Cranston, stands on a platform waiting for his free skating marks. Wilf Langevin announces the marks from the judges as seven people hold up scores on large cards.

A close-up of Toller’s face is inset in the screen at the upper left.

Transcript:

[Applause throughout. No music.]

Well now in this one, a few more sixes, I’m betting.

Judge number one: five point eight.

Judge number two: five point nine.

They’re afraid to give sixes, some of them!

Judge number three: six point zero.

There’s a six!

Judge number four: five point nine.

Judge number five: six point zero.

There’s another six! That’s three so far!

Judge number six: six point zero

That’s four!

Judge number seven: five point nine.

Toller Cranston! Oh man, that’s a great performance!