Age of Discovery

1600

1860

Overview

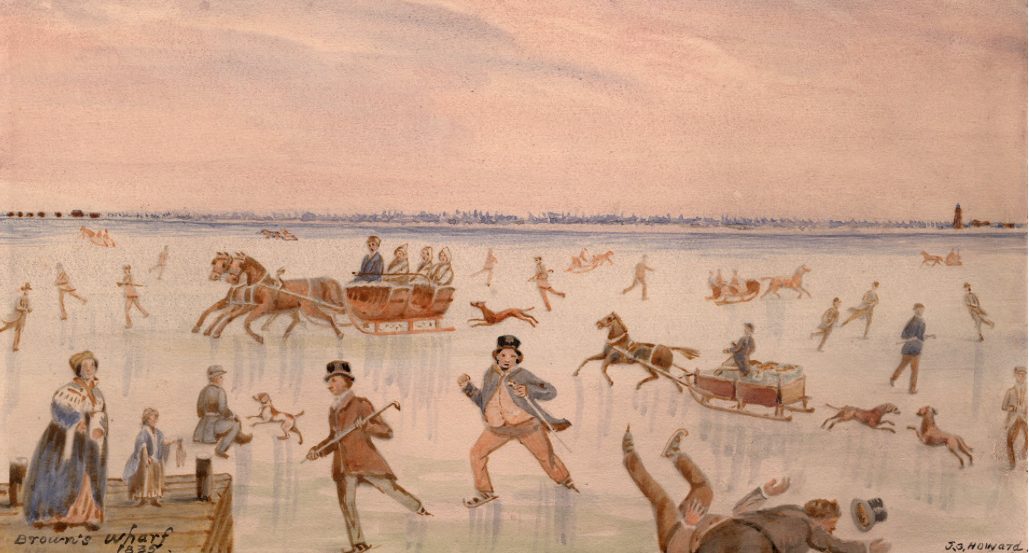

Toronto Bay, skating scene, by John George Howard, 1835. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

In this chapter we will explore the roots of figure skating by looking at books, letters, paintings, and other sources. We will trace the history of figure skating from its early origins and growing popularity in Europe to its arrival in Canada with early settlers, explorers, and the military, who used the form for leisure, transportation, and commerce. Find out where the first skating club in Canada was located, who developed the earliest figure skates, and who wrote the first instructional books on the sport.

These fancy leisure skates would be bound to the wearer’s boot with leather straps. Europe, c. 1780-1820. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P16.6

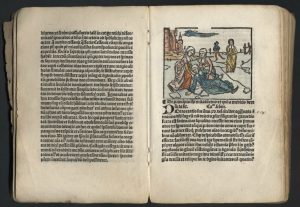

What was the first published image of skating?

What was the first published image of skating?

One of the earliest known images of ice skating in Europe appeared in 1498. The woodcut, depicting Saint Lidwina, the patron saint of ice skating, was published in a hagiography, or lives of the saints, by Franciscan friar Johannes Brugman.

Boots & Blades

Wrought iron blades featuring an extended toe curl are mounted to the wood platform on metal posts. Leather straps are missing. C. 1780-1850. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S80.1697

Early Settlers Document Skating in North America

New economic growth in the 16th and 17th centuries meant that people had more time for leisure activities. Skating’s popularity grew exponentially during this period, especially in England, Russia, and northern Europe. Metal blades strapped onto boots replaced earlier bone and wooden sliders.

Found in Quebec, this skate still has the leather bindings used to strap the blade to the wearer’s boot. C. 1800-1850. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P80.1700

Scroll across the screen here to see skates from the late 1700s and early 1800s in the Bata Shoe Museum Collection:

Pierre Dugua de Mons, an early explorer to New France, kept a diary of his experiences. In 1604, he settled on St. Croix Island in the Bay of Fundy. He noted: “During the winter some of the young men went hunting in spite of the cold weather. They went skating on ponds.”

The “violin” shaped platform was used in Europe, but these are American skates made by Douglas Rogers and Co. of Norwich, Connecticut. C. 1850-1870. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S80.1709

Early settlers and explorers brought their skates with them to North America, stowing ice skates in their luggage. The letters of 18th-century British explorer and officer Thomas Anburey describe the immense popularity of the sport among British officers in North America. The sport was so popular, Anburey recalled, owing to “there being such a constancy and large extent of ice.” Stationed near Quebec City with the British Army’s 47th Regiment of Foot in 1789, Anburey remarked that “there are several officers in the regiment, who being exceedingly fond of it, have instituted a skating club, to promote diversion and conviviality.” Anburey mentions that Indigenous peoples also skated.

These have a cut-out heart-shaped design. The bottom of the blades are honed with edges to allow the skater more control. North America, c. 1850-1860. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P82.146

Scroll across to see skates from the 1840s to the 1870s in the Bata Shoe Museum Collection:

The sport had grown so popular that in 1748, François Bigot, a French Government Official, issued an ordinance prohibiting people from skating on Quebec’s streets.

An unusual blade design of metal alloy with brass detail. Possibly France, c. 1850-1860. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P82.79

This pair has nickel-plated brass ankle supports and is stamped “BLONDIN SKATES PATD Oct.2 1860”. Made by the Douglas Rogers & Company in Norwich, Connecticut, c. 1860s. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P88.23

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries most skates were imported from Holland, Germany, France, and England. The popularity of skating saw the beginning of homegrown Canadian skate manufacturing develop by the mid-19th century.

Scroll across to see skates from the 1850s and 1860s in the Bata Shoe Museum Collection:

This cage-like design was patented by “Shirley’s” in 1859. It is an all-metal blade that clamps onto the wearer’s boot, adjusting for size at the heel. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P88.22

What did people use before metal skates were invented?

What did people use before metal skates were invented?

People used animal bones strapped to the bottoms of their shoes to traverse frozen bodies of water. Skaters would use long poles for added balance and momentum. Skating in this early period was primarily a form of transportation rather than a recreational activity.

Early Skate Technology: The Dutch Influence

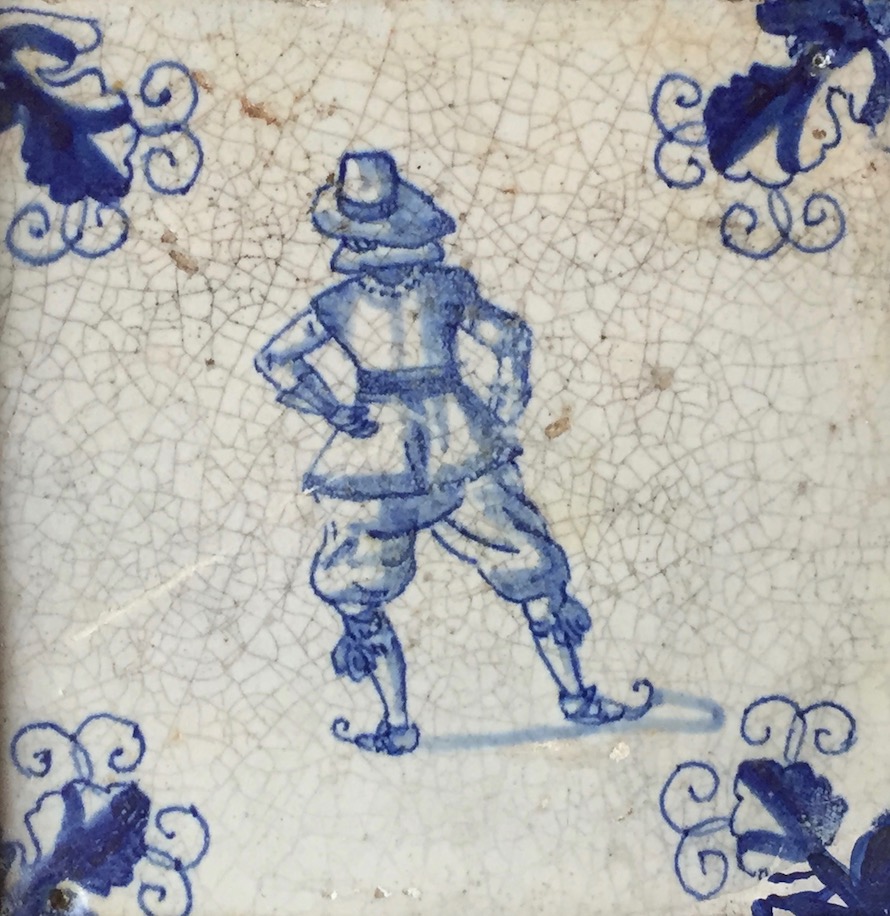

We can learn a lot about early ice skating in Europe through its depiction in Netherlandish art. The artistry and technical challenge of the sport are captured in many media, from Delft pottery tiles to paintings and etchings.

Delft ceramic tile with illustration of a Dutch skater. Holland, c. 1650. Astra Burka Archives

Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters by Hendrick Avercamp, c.1608. Collection of the Rijksmuseum

The quintessential Dutch skates were known as “sliders”. Skaters would attach metal blades to their shoes by way of a wood platform and leather straps.

Skate Maker. Engraving by Jan Luyken, 1694. Collection of the Rijksmuseum.

The Breinermoor style skate was first made around 1750. This example was found in Holland, c. 1750-1850. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P85.57

These sliders allowed for ease of movement on frozen canals, lakes, and ponds. Baroque artist Rembrandt’s etching of a male figure skater captures the fluidity of movement made possible by wearing these Dutch skates.

The Skater by Rembrandt, 1639. Collection of the Rijksmuseum.

Even Thomas Anburey notes the Dutch influence on ice skating, as he remarked in 1789 that the “Canadians skate in the manner of the Dutch, and exceedingly fast.”

Scroll across to see skates from 1750 to 1850 in the Bata Shoe Museum Collection:

Who was the first metal skate-blade producer for Royalty?

Who was the first metal skate-blade producer for Royalty?

King William III of England commissioned John Wilson, a tool maker, to make him a pair of metal blades in 1696. In 1840, the merged company John Wilson, Marsden Bros. & Co. Ltd. were commissioned to make skates for England’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Movement

Modern figure skating involves jumping, spinning, and complex figures. Early skates were not yet developed enough for these; moving forward was the main goal.

Blades made of metal were used from the 14th century onwards for purposes as varied as transportation between towns, trading and commerce, to visit friends, and simply for leisure. Hand held poles were sometimes used for balance and momentum.

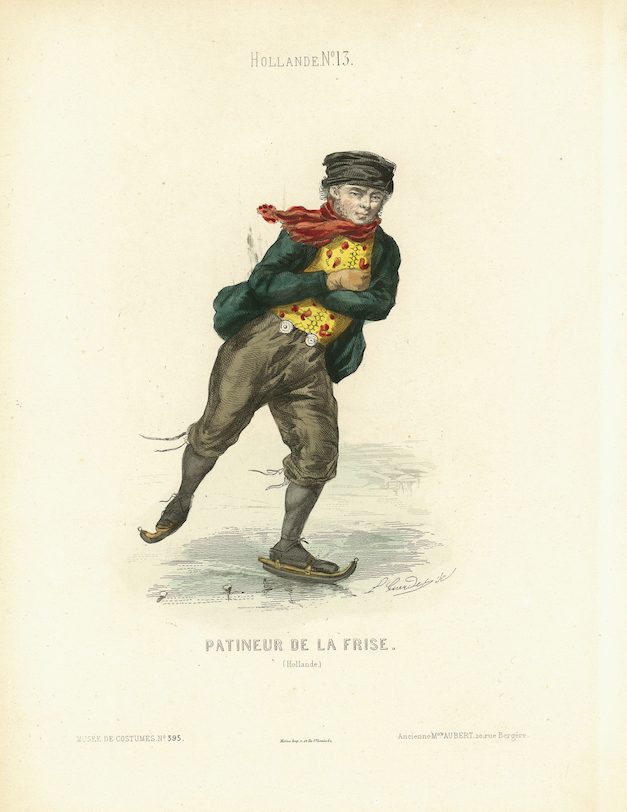

Skater from Friesland, engraving by Elchanon Verveer, c.1850-1863. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P83.223

Robert Jones: An Early Skating Instructor

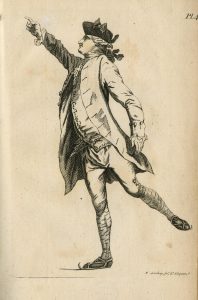

Englishman Robert Jones’s book A Treatise on Skating is described by its author as being founded on “many years of experience” by which the “noble exercise” of skating “may be taught and learned by a regular method.” Jones outlined early fundamental principles of the sport, including diagrams of skating figures. Some early skating figures included the Flying Mercury, the Fencing position, the Serpentine Line, and the Spread Eagle. Jones’s work, first published in 1772, is the earliest-known documented book on the art form.

Skaters discovered that taking long strokes and leaning along the outside or inside of the skate ensured continuous movement on the ice, movement that was both artistic and practical. Moving along in this way became known as the Dutch roll.

Ice Skating in a Village by Hendrick Avercamp, c.1610. Collection of the Rijksmuseum

The discovery of the Dutch roll, or rolling, was an early development towards figure skating. The continuous movement was clearly defined by the 16th century. The English later developed figures using the Dutch roll as their foundation.

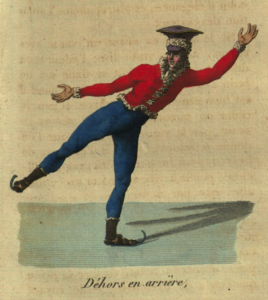

Jean Garcin: French Artistry Influences the Sport

Jean Garcin published Le vrai patineur ou Principes sur l’art de patiner avec grâce (The True Skater or Principles of the Art of Skating with Grace in English) in 1813 in France. Influenced by ballet, French skating emphasized beauty of form and grace of execution. Skating backwards became part of the art form. More movements meant that skaters needed larger areas of ice on which to practice. Garcin’s illustrations of over 30 different free-skating positions are as beautiful as they are varied. Many of these are still used by skaters today.

Where was Canada’s first organized skating club?

Where was Canada’s first organized skating club?

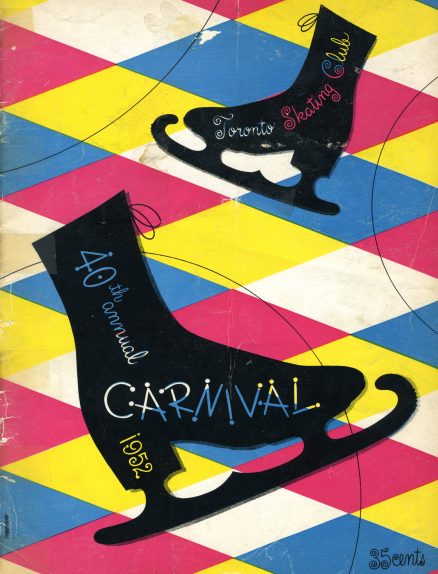

Saint John, New Brunswick was the site of the first organized skating club in Canadian history. Founded in 1833, 34 years before Confederation, Lily Lake skating club was a popular destination for skating enthusiasts.

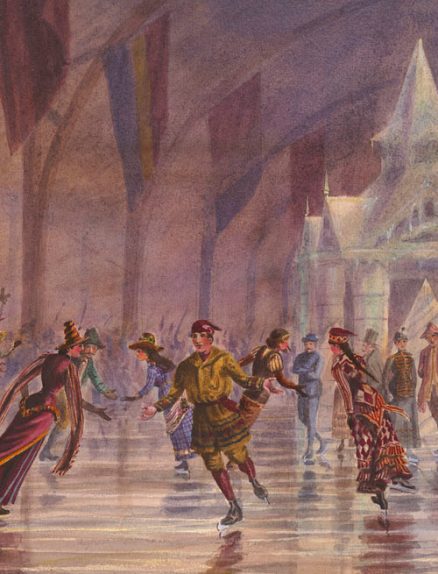

Costume

Elaborate costumes are a quintessential part of modern figure skating. In skating’s early days, fashion on the ice ranged from the latest trends to everyday workwear. Clothing would need to be warm and layered.

Skaters on the Ice by Hendrick Avercamp, c.1620-1625. Collection of the Rijksmuseum

Paintings by the Dutch masters in the 17th century depict villagers out and about on the ice wearing clothing typical of the period.

Skaters on the Amstel by Arent Arentsz, 1620. © Art Gallery of Ontario

Perhaps one of the most famous images of a skater is Scottish painter Sir Henry Raeburn’s 1795 portrait of Reverend Robert Walker, which Raeburn affectionately titled The Skating Minister. It seems as though Reverend Walker is about to skate off to give a sermon.

The Skating Minister by Henry Raeburn, 1790s. © National Gallery of Scotland

More regional paintings, like early Toronto architect John Howard’s painting of skaters on Toronto Bay in 1835, depict skaters dressed in early Victorian attire jostling for space with sleighs and pedestrians out on the ice.

Brown’s Wharf by John George Howard, 1835. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

Music

Although music plays a pivotal role in any contemporary skating program, music was not as important a component out on frozen bodies of water. The ability to project music across large open spaces was perhaps not yet considered, as it is not necessary for leisure skating. However, the pastime was highlighted in popular song. One, “The Skater’s March”, was composed for the Edinburgh Skating Club, one of the earliest skating clubs in Scotland. Published in the 1780 edition of Jones’s Treatise on Skating, the lyrics of the cheerful song reference early figure-skating movements:

From right to left we’re plying

Swifter than winds we’re flying

Spheres on spheres surrounding

Health and strength abounding

In circles we sweep

Our poise still we keep

Behold how we sweep

The Face of the Deep