Age of Internationalism

1945

1965

Overview

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Plane arrives in Vancouver, B.C. with the Canadian team for the 1960 World championships. © Skate Canada

An airplane arrives on a runway after a flight. A group of people exit the plane, all wearing matching striped Hudson Bay blanket 1960 Olympic team coats. They are smiling, proud and carrying their luggage.

Transcript:

[no sound]

World War II ended in 1945, and Europe was in ruins. The World Championships, all international competitions, and European skating competitions had stopped in 1939. European skaters paused their training; international competitions did not resume until 1947.

Away from the theatre of war, North American skaters continued to train. This opportunity gave them a distinct competitive advantage. Canadian competitions continued throughout the war years. The only year that the Canadian Championships were not held was 1943.

The International Skating Union decided that after 1948 Canadian and American skaters would no longer be allowed to compete in the European Championships. Biennial North American championships were held from 1923 to 1971.

Internationally, Canadian skaters were on the podium at the World and Olympic Championships. They won a total of 37 medals across both championships, compared to just four before WWII.

New technological innovations spurred the sport forward. Air travel meant that skaters could more easily take part in international competitions. New boot and blade designs helped skaters execute more difficult skating moves. Skaters included double and triple jumps, faster spins, and intricate connecting steps in their complex routines.

By the mid-1950s, audiences could tune in on their black-and-white televisions from the comfort of their homes to watch their favourite skaters compete internationally.

Who was the first female skater to land a triple jump in an international competition?

Who was the first female skater to land a triple jump in an international competition?

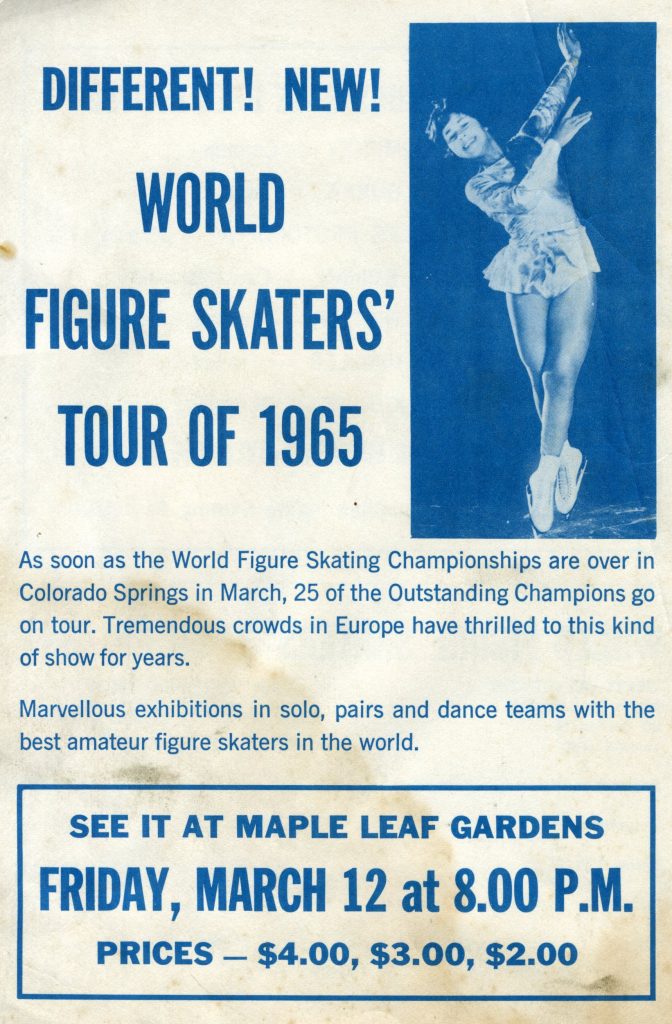

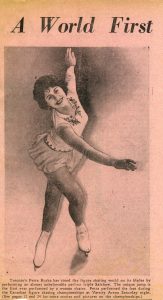

Canadian Petra Burka was the first female skater to land a triple jump in an international competition. She landed a triple Salchow in 1962.

CANADIAN GOLD CHAMPIONS ON THE WORLD STAGE!

Barbara Ann Scott, the first Canadian skater to win a gold medal at the Worlds and Olympic Games. World Champion 1947, 1948, Olympic Games 1948.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Barbara Ann Scott skating at the World Championships, Prague, 1948. © Skate Canada

Barbara Ann Scott, wearing a long-sleeved sparkly costume, performs a double loop jump and a layback spin while an audience applauds her in the background.

Transcript:

[Music: lively jazz instrumental music]

Francis Dafoe and Norris Bowden, the first Canadian pair skaters to win Worlds. World Champions 1954, 1955.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Francis Dafoe and Norris Bowden performing a spin lift, c.mid 1950s. © Skate Canada

After Norris Bowden performs a deep outside back edge, Frances Dafoe jumps from the ice into his arms. He catches her and holds her in the air while they perform a graceful, spinning lift. Norris sports a formal skating suit and Francis wears a traditional short skating dress.

Transcript:

[soft classical instrumental music]

I look at pair skaters and…

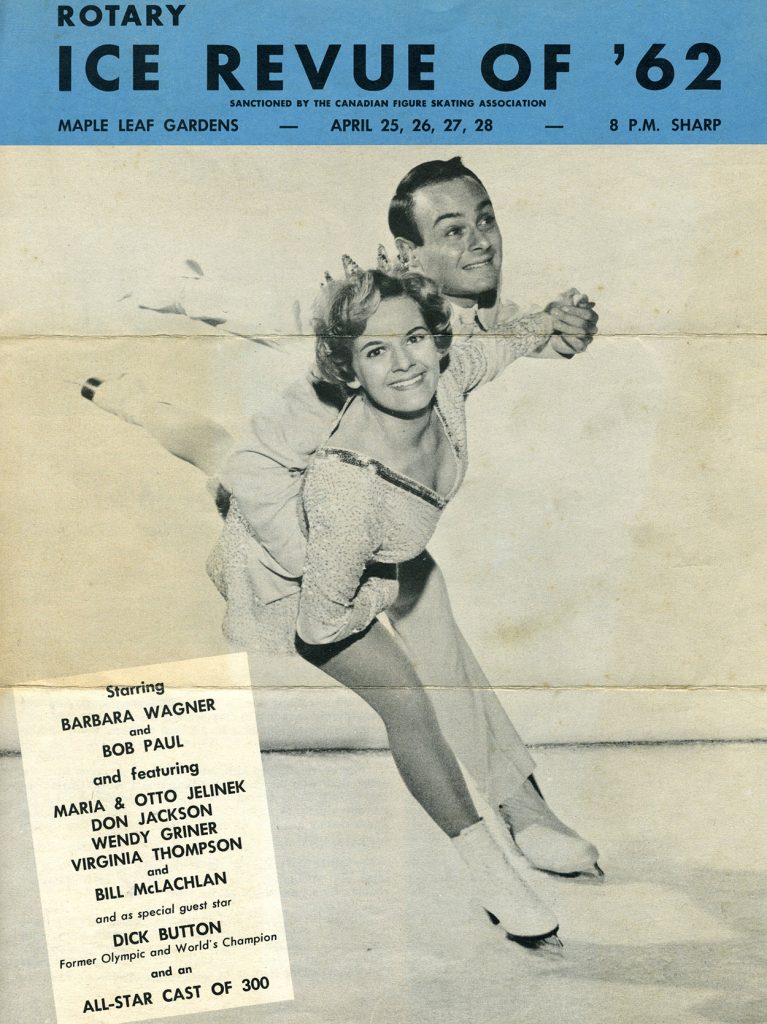

Barbara Wagner and Robert Paul, the first Canadian pair to win Olympic gold medals. World Champions, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, Olympics 1960.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Barbara Wagner and Robert Paul skating at the World Championships, Colorado Springs, 1957. © Skate Canada

In an area filled with spectators, Wagner and Paul skate together in pair unison around the ice, performing a double loop jump lift and side-by-side Axels.

A series of side-by-side footwork down the ice continues as they hold hands in another series of footwork and two lifts.

Transcript:

[lively orchestra music]

[uplifting orchestra music]

Maria Jelinek and Otto Jelinek, World Champions 1962

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Maria and Otto Jelinek at the North American Championships, Philadelphia, 1961. © Skate Canada

Maria and Otto Jelinek skate around the ice in unison, performing an outside edge death spiral, then a very high and almost still lift, followed by a side-by-side lunge, while an audience applauds.

Transcript:

The Statue of Liberty lift, coming up.

Again, a beautiful death spiral, just beautifully performed.

[applause]

Here’s the Statue of Liberty lift.

[Music: Dramatic orchestra music from either Antonín Dvořák or Bedrich Smetana]

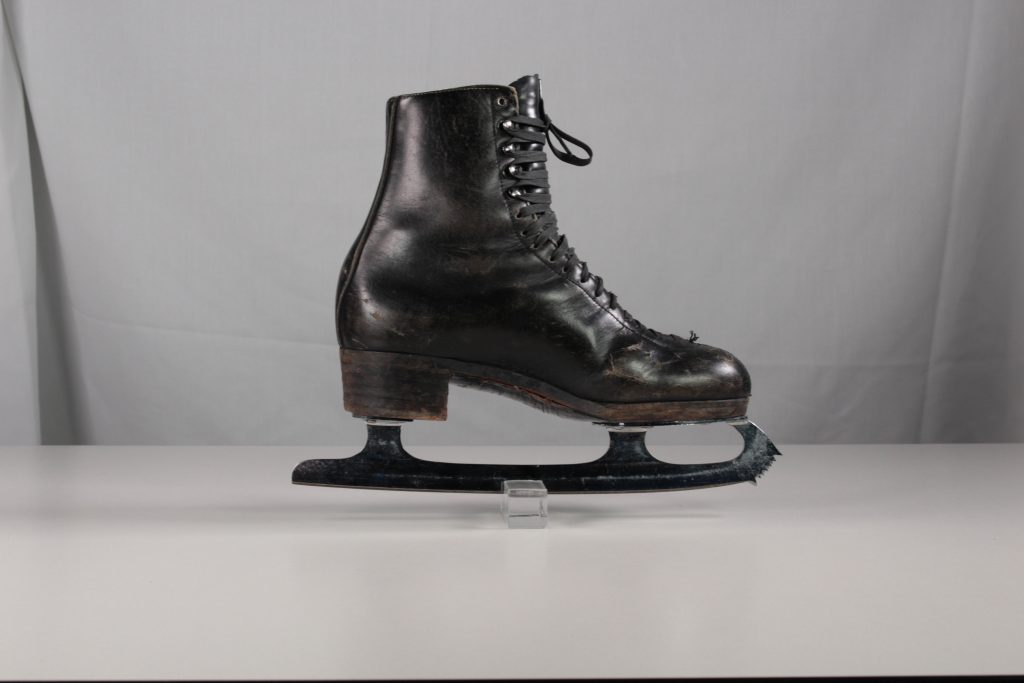

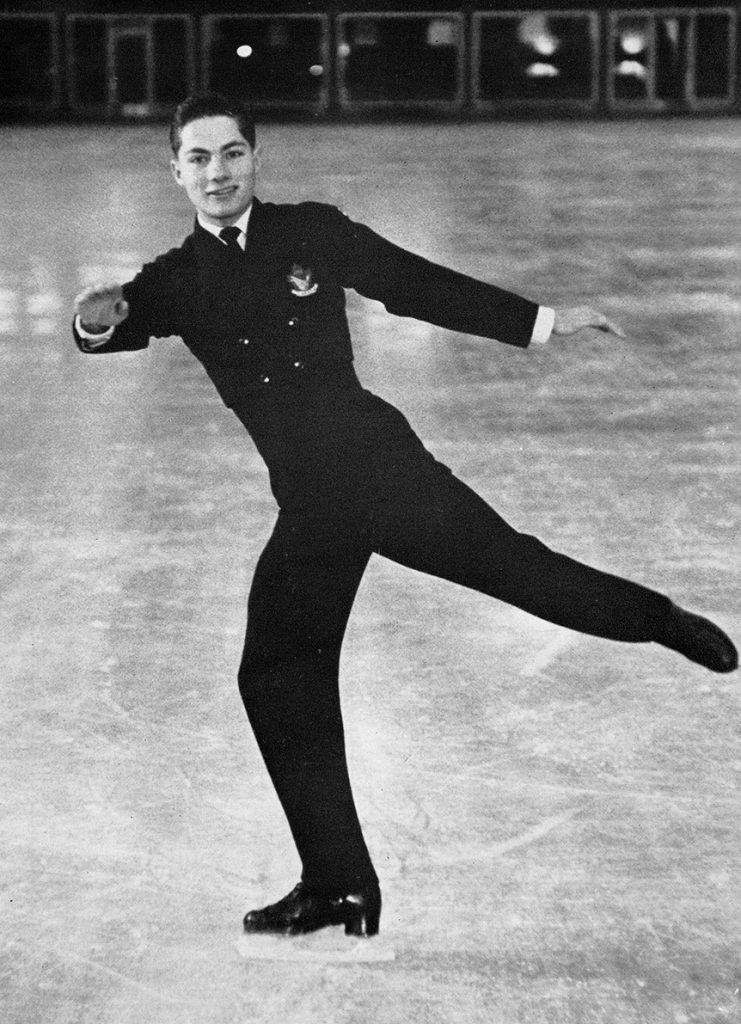

Donald Jackson, the first Canadian male skater to win the Worlds. World Champion 1962.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Donald Jackson skating at the World Championships, Prague, 1962. © Skate Canada

Don Jackson, wearing a black suit and tie, skates around the ice, landing the second triple jump of this program, and finishing with a flying sit spin.

An indoor arena filled with spectators applauds his success.

Transcript:

Donald Jackson has a minute and a half left of his five-minute allotted time.

[applause]

Coming up now into his second triple jump, a triple salchow, again three revolutions.

[applause]

Beautifully done, followed by a [fine] flying sit spin.

He now has one minute to go, he’s skating a great performance.

[Music: Carmen by George Bizet, “Opera for Orchestra, Act I,” André Kostelanetz and His Orchestra]

Don McPherson, World Champion 1963

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Donald McPherson skating at the North American Championships, Philadelphia, 1961. © Skate Canada

Don McPherson, wearing a fitted black suit and tie, lands a double loop and then skates around the ice before launching into a flying split jump and a series of jump camel and sit spins.

Transcript:

[dramatic orchestra music]

[applause]

Double loop. Very beautifully done, flying camel into a flying jump sit spin.

[applause]

Petra Burka, World Champion 1965

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Petra Burka skating at the World Championships, Colorado Springs, 1965. © Skate Canada

Petra Burka, wearing a long-sleeved costume with traditional short skating skirt and deep neckline in front and in back, skates around the ice.

She gracefully executes a double axel with her hands above her head and a double lutz with one arm above her head in a ballet position.

Transcript:

[Music: Tchaikovsky and Beethoven - soft, slow orchestral music]

A double axel but watch the arms. That shows complete control to be able to vary the arms like that.

[applause]

Here comes a similar variation and a double lutz jump coming up.

Once again, watch the arms and the height of the jump.

[applause]

Who was the first male skater to land the triple Lutz jump in an international competition?

Who was the first male skater to land the triple Lutz jump in an international competition?

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Donald Jackson skating at the World Championships, Prague, 1962. © Skate Canada

Canadian Donald Jackson was the first male skater in the world to land a triple Lutz jump. He did it in Prague at the 1962 World Championships.

Boots & Blades

Canadian Skate Boot Making

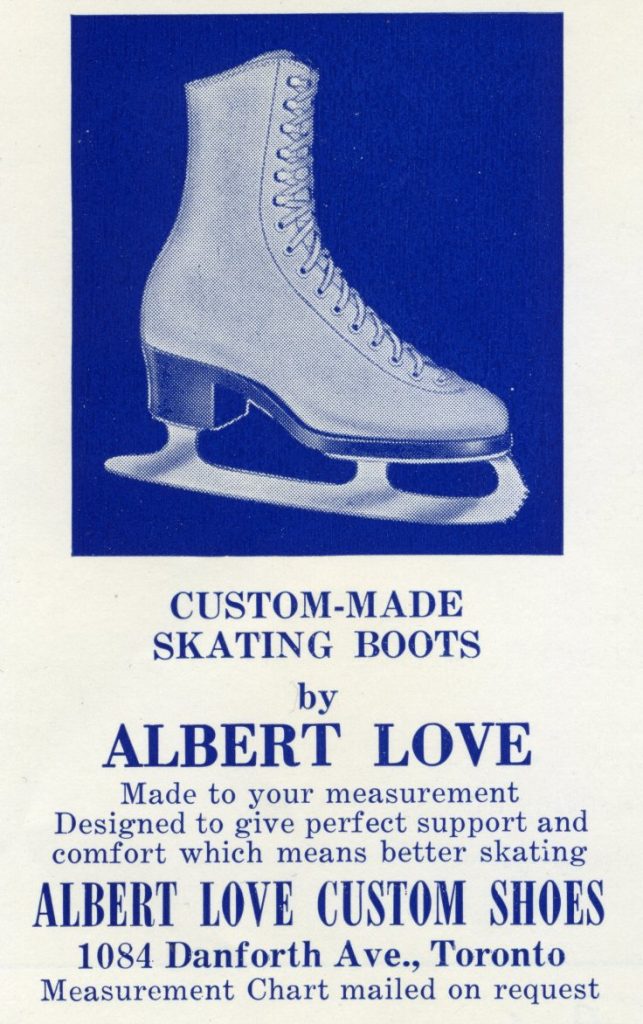

John Knebli advertisement, Toronto Skating Club Carnival program, 1954. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Hungarian immigrant John Knebli, a master orthopaedic shoemaker, opened his custom shoe service in Toronto in 1944. Soon after, a skating coach challenged him to make a pair of skating boots for the coach’s student. The coach wanted the boot design improved, so he supplied Knebli with an existing one for research. Using his knowledge of podiatry and the dynamics of the body in motion, Knebli soon developed an improved design for custom skating boots.

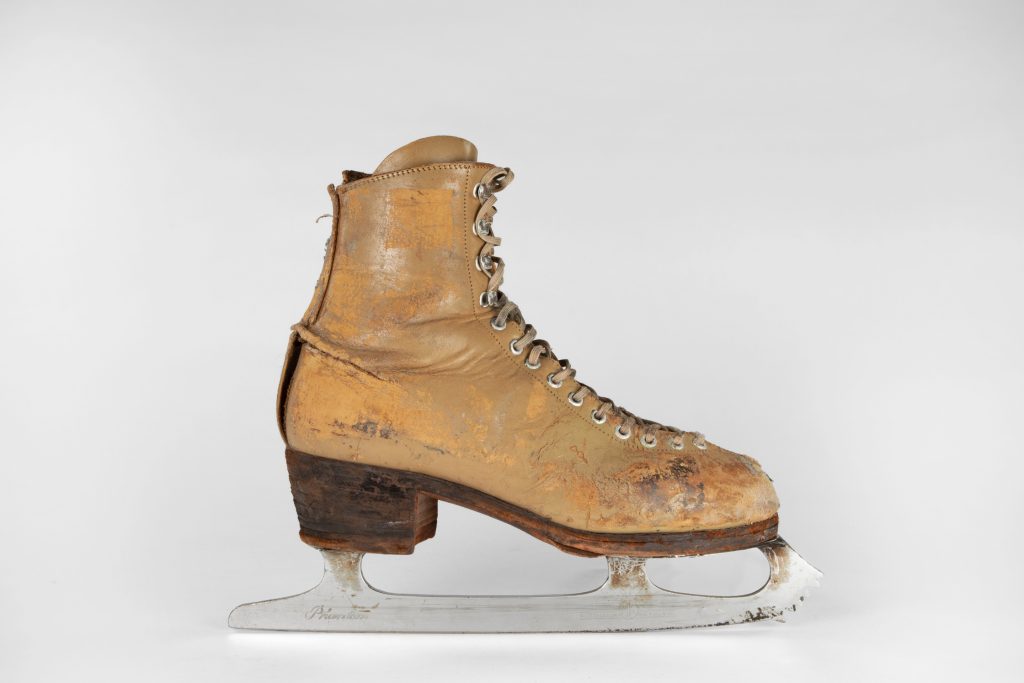

Ellen Herron’s custom made buckskin Knebli boots, cut high on the ankle requiring seven hooks, fitted with “Four Aces” model John Wilson blades, 1957. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S14.7

Creating a pair of custom-fit handmade boots took about two weeks. Knebli developed specialized leathers with the tanners at Braemore Leathers in Cambridge, Ontario to get the damp-resistant finishes he needed for the boots. He ordered the most flexible leather for figure boots and the stiffest of leathers for free-skating boots. Leather for ice-dancing boots fell somewhere in the middle. Once the boots were constructed, an appropriate blade would be selected from suppliers such as John Wilson, and the blade was attached to the boot, at which point the skater could test it on the ice.

Astra Burka’s custom Knebli boots with buckskin uppers, but cut slightly lower on the ankle than his earlier work. Fitted with “Taylor Special” John Wilson blades, 1961. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P14.6

Knebli devised an innovative solution for champion skater Barbara Wagner in the 1950s. He felt that, esthetically, a low-cut boot would add a look of elegance, making short-legged skaters appear taller. He cut down the upper part of the boots so that they had four hooks instead of the standard five or six. Greater ankle flexibility was another benefit of the new low cut. To maintain the ankle support, he enhanced the strength of materials in the ankle area. Soon all the boots he produced were low-cut. Other makers around the world followed.

Knebli’s custom boots were a high-end option for figure skaters who were at the height of their careers. Knebli was the first custom boot maker in Canada. Others, such as Ed Rose, in the Cambridge area, came in later decades.

Companies like Daoust in Montreal, Bauer in Kitchener, and CCM and Albert Love in Toronto offered affordable mass-produced options for the beginner skater.

Canadian Brands

American Brands

Blade Innovation: New Designs for Free Skating

Pattern 99

Coaches collaborated with craftspeople to design more specialized blades for their students. In 1960, Coach Ellen Burka worked with custom boot maker John Knebli to craft a new free-skating blade for Burka’s daughter Petra. The blade became known as Wilson’s Pattern 99; it was, and still is, manufactured by John Wilson in Sheffield, England.

Petra Burka’s skates fitted with “Pattern 99” blades manufactured by John Wilson, c. 1966-1969. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P14.5

Detail view of the toe pick and model marking on Petra Burka’s “Pattern 99” blade, c. 1966-1969. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P14.5

What made the Pattern 99 blade revolutionary? The aggressive toe-pick design gave skaters a strong grip on the ice when taking off during jumps. Pattern 99 soon became the blade of choice for Canadian and international champion free skaters.

Gold Seal Redesigned

Donald Jackson and his coach Pierre Brunet were unhappy with the Strauss blades he was using, so they collaborated with Wilson to redesign the Gold Seal. The major innovation was the creation of slotted holes in the mounting plate that allowed for perfect placement of the blades according to the skater’s stride and alignment.

John Wilson advertisement featuring the name of Don Jackson, 1962. Astra Burka Archives

Movement

The Versatility of Skating Coaches

Demand for talented new coaches increased as skating clubs continued to spring up across the country.

Former European champions Marcus Nikkanen, Ellen Burka, Lilianne de Kresz, and Edi Rada taught skaters in Canada. They joined Canadian coaches including Sheldon Galbraith, Osborne “Ozzie” Colson, Gerrard “Gerry” Blair, Ron Vincent, Margaret and Bruce Hyland, and Alex Fulton. Champion British ice dancer Jeanne Westwood trained top Canadian ice dancers. These coaches taught some of Canada’s top talent. For example, Marg and Bruce Hyland coached World Pair Champions Maria and Otto Jelinek and medallists Debbi Wilkes and Guy Revell. Ellen Burka coached Canada’s first World Champion, her daughter, Petra Burka. Ellen coached other international competitors too, including Donald Knight, Jay Humphry, and Valerie Jones. Sheldon Galbraith taught more international gold medallists than any other coach: he taught Barbara Ann Scott, Frances Dafoe and Norris Bowden, and Barbara Wagner and Robert Paul. Galbraith’s other students in the international competition circuit were Wendy Greiner, Donald Jackson, Valerie Jones and Donald Knight.

These coaches were multitalented generalists. In the free-skate event, they oversaw choreography and musical interpretation and adapted ballet and modern dance moves to the ice. They also selected music that would showcase their skaters’ talents and encouraged skaters to improve their artistic abilities with “off-ice” dance training.

Boris Volkoff School of Dance “Annual Dance Recital” poster, 1953. Astra Burka Archives

Coaches’ technical knowledge improved skaters’ execution so they could achieve increasingly difficult spins, jumps, and connected steps. Athletic skating elements were still the most important aspect of a free-skate program, but many coaches were keen to introduce more artistry.

Who was the only Canadian skater to win the European Championships twice?

Who was the only Canadian skater to win the European Championships twice?

Barbara Ann Scott won the European Championships in 1947 and 1948.

Skating by the Rules

Training for competitions was nothing if not rigorous. Single skaters had to train for six hours a day: four hours of figures and two hours of free skating. They performed both figures and free skating to fulfill the requirements of the Singles category in competition.

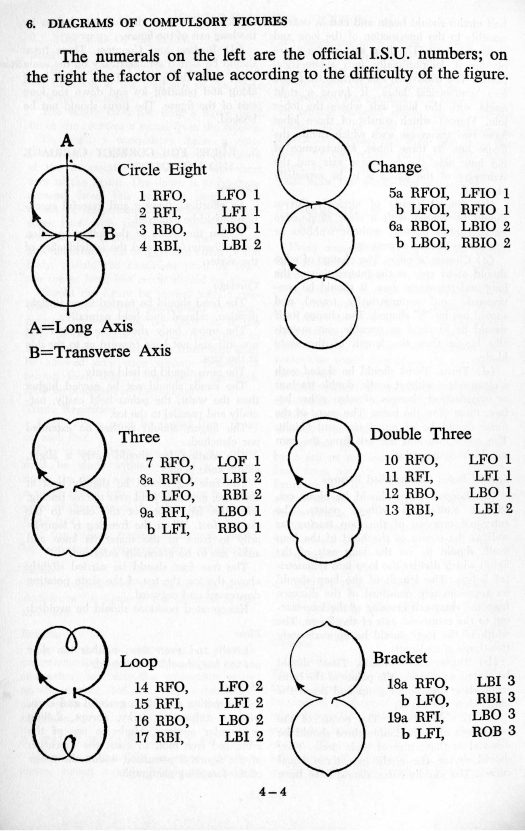

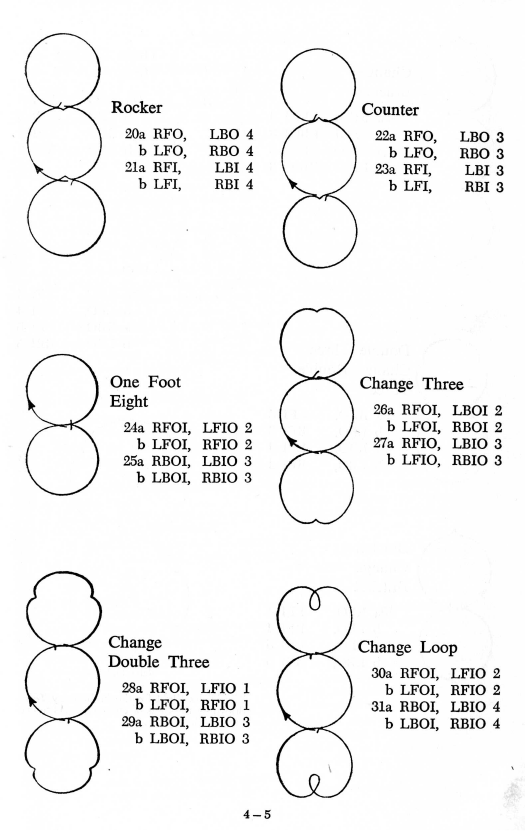

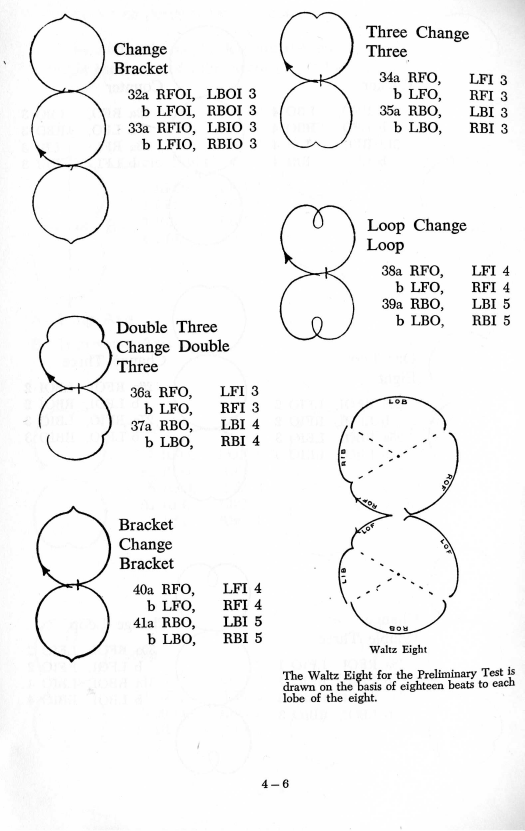

A. Figures

The figure category still counted for 60% of a skater’s final mark in competitions. This very quiet aspect of the competition took two days! It was never televised. To see the figure tracings in detail, you need to be on the ice. The Canadian Figure Skating Association (CFSA) presided over skating tests and national competitions. The International Skating Union (ISU) regulated international competitions.

Before the War, skaters did not need to close the centre point of their tracings of circles and loops, which meant that there was a gap between the circles. Now skaters were expected to close the geometric shapes they traced, which is more technically difficult.

Barbara Ann Scott skating a loop figure, c.1947-48. © Skate Canada

To practise for competitions, figure skaters had to learn and perfect 41 figures. These figures were performed on the outside and inside, forward and backward edges of both feet. The ISU would randomly select six of the 41 figures to be performed at each competition.

In addition, skaters had to pass a gruelling eight levels of figure-skating tests to qualify for national and international competitions.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Video of Carol Heiss performing required figures for the judges at the 1960 World Championships in Vancouver, 1960. © Skate Canada

A female skater executes a set of forward-to-backwards counter figure eight, in which the turns connect three circles. Skated on one foot.

She skates three large circles, one on top of the next, with a counter turn done at the point where they touch.

A group of judges examine the tracings she has made on the ice and at the end stand in a line, holding up their score given to the skater using pallets, each with one number on it. Each judge holds two numbers.

Transcript:

[no sound]

B. Free skating

Petra Burka jumping in four time-lapse segments, 1963. Astra Burka Archives

Carol Heiss

American skater Carol Heiss was the first woman to land a double Axel, in 1953. (Women did not perform jumps as part of their programs before 1920.) After WWII, women started experimenting with their jumping technique, adding double rotations to several types of jumps. Heiss combined technical prowess, musicality, and athleticism into her routines.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Carol Heiss skating at the World Championships World Championships, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, 1956. © Skate Canada

Free skating advanced quickly technically, but at a slower pace artistically. Women pushed themselves to land powerful double jumps. Men, who had been practising double jumps for about a decade, now attempted triples. New spins like the flying camel and the sit spin became popular. Free-skate programs lasted four minutes for women and five minutes for men. During this period, free skating only accounted for 40% of a skater’s marks.

Dick Button: Jumping & Spinning

American Dick Button was the first to win the World, Olympic, and European Championships after WWII. He was the first skater to land a double Axel (1948) and a triple loop at the competitive level (1952). He invented the flying camel spin, now a popular element in skating programs.

Button trained with famed coach Gustave Lussi, who determined the best positions for powerful jumps and spins using his engineering background.

From 1948 to 1960 American men had a long winning streak at Worlds and Olympics. In addition to Dick Button, the brothers Hayes Allen Jenkins and David Jenkins were on the podium at international competitions.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Dick Button skating at the World Championships, Paris, 1952. © Skate Canada

C. Pairs

Pairs skated a five-minute program. Although they routinely performed vertical lifts, soon they were being lifted over their partners’ heads and turned through the air. New throw jumps became more intricate. Any pair skater who performed these elements needed superior control and poise.

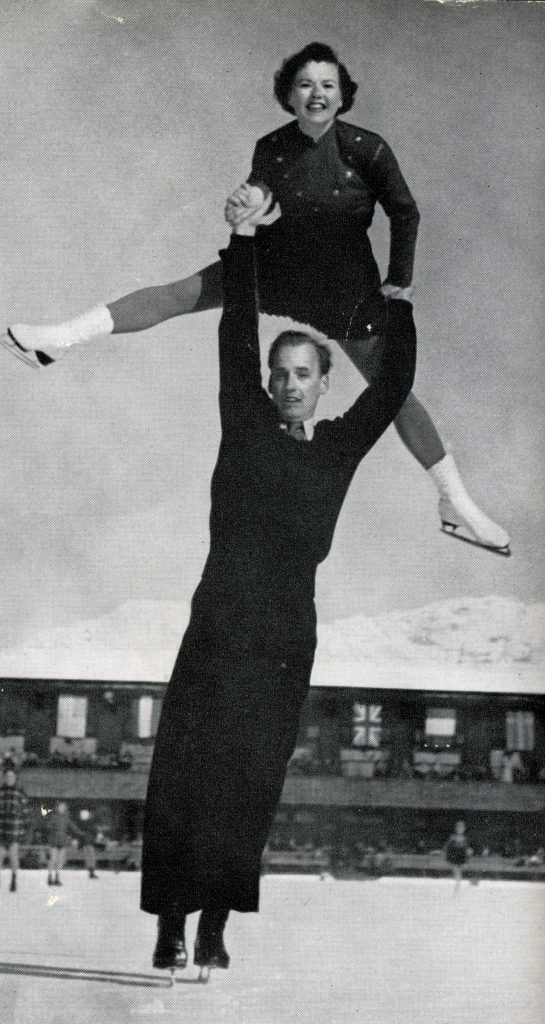

Frances Dafoe and Norris Bowden performing an overhead lift, Toronto Skating Club Carnival, 1953. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

Canadian bronze medallists Suzanne Morrow and Wallace Diestelmeyer were the first pair to perform the one-handed death spiral in a competitive setting—the 1948 Olympics. The death spiral, invented by Charlotte Oelschlagel in the 1920s, was originally a two-handed move. Today, it is a popular element in many pair-skating programs.

Suzanne Morrow and Wallace Distelmeyer skating a spiral together. Toronto Skating Club Carnival program, 1948. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

The Protopopovs & Artistic Skating

Husband-and-wife pair skaters Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov of the USSR were both ballet-trained. When they stepped out on the ice, they wowed audiences with performances influenced by the Bolshoi Ballet. They ushered in new artistic possibilities for ice skating.

Soviet skaters did not compete internationally between 1917 and 1956 due to the political situation in their country.

We have detected that your Javascript is disabled. We're sorry, the videos are not available without javascript.

Ludmilla Belousova and Oleg Protopopov skating at the World Championships, Geneva, 1968. © Skate Canada

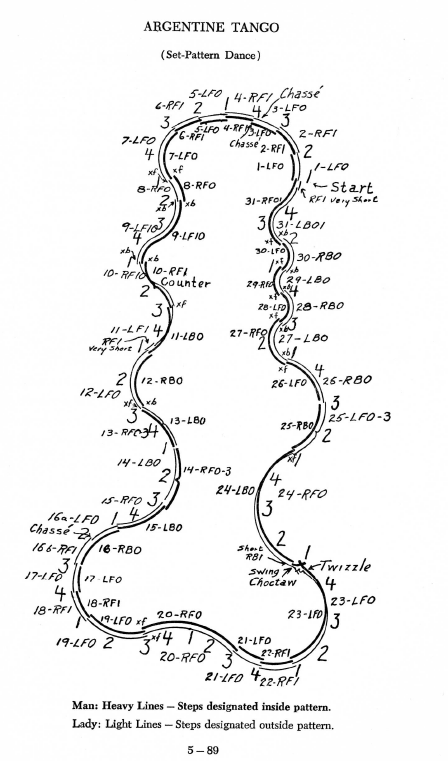

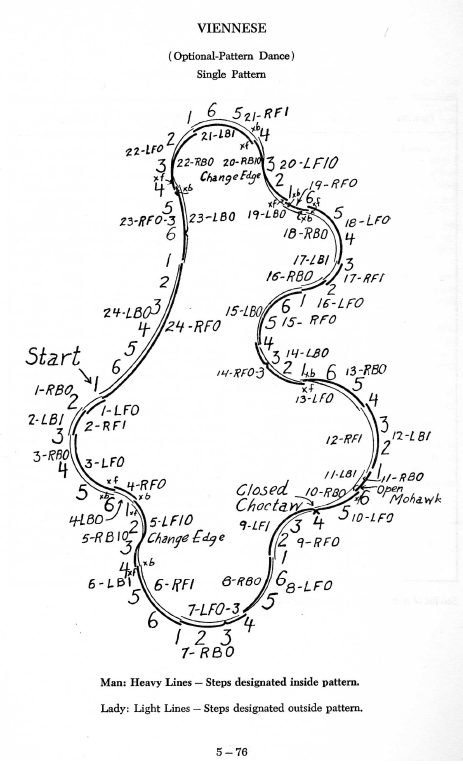

D. Ice dancing

Ice dancing became an official category at the World Championships in 1952. Star British skaters influenced the style’s development during this period.

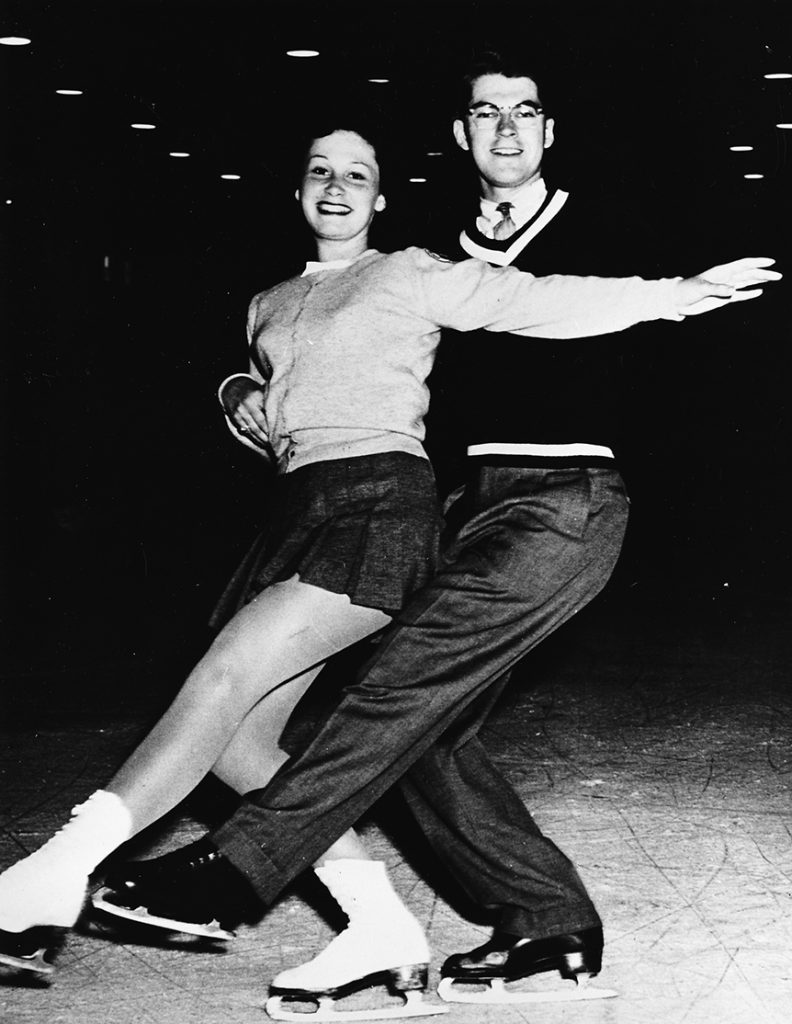

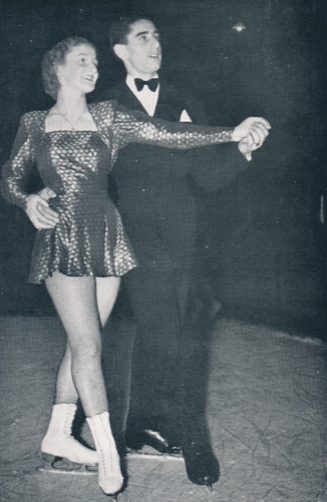

Canadian skaters excelled in this category as well. William McLachlan and Geraldine Fenton won five medals at the World Championships. Later, McLachlan partnered with Virginia Thompson, and they won two medals. Torontonians Kenneth Ormsby and Paulette Doan won the Canadian Championships in 1963 and 1964. The two skaters even toured with the Ice Follies; they later married.

Ice Rinks

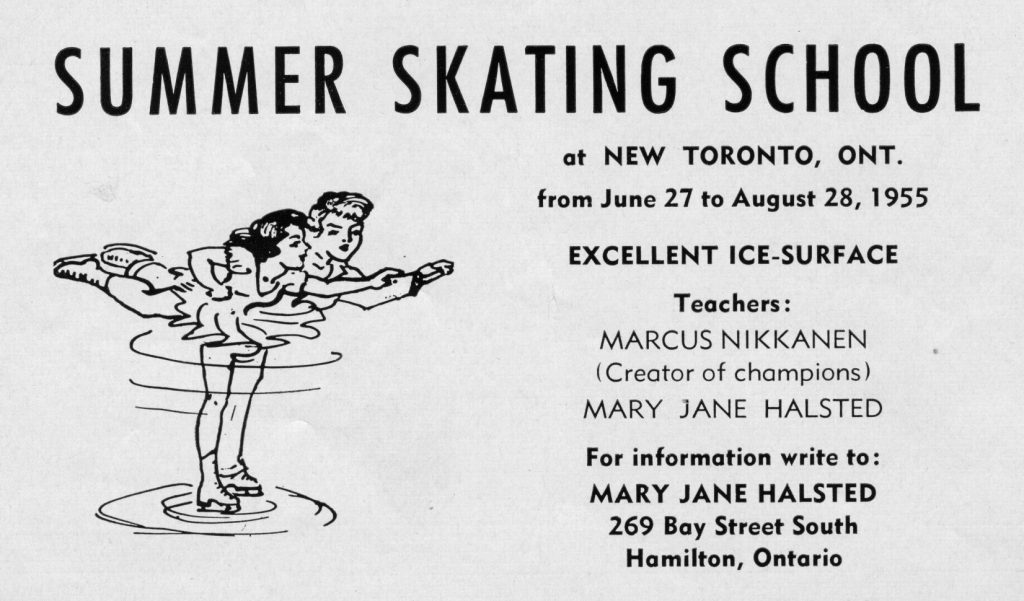

Advertisement for Summer Skating School, The University Skating Club, Souvenir Program, March 26,1955. Astra Burka Archives

Figure skaters still shared public rinks with ice-hockey teams, but private skating clubs provided ice full-time during the winter season. Any serious skater who wanted to perfect their art but did not belong to a private club rented extra ice time with their coaches at local rinks. How could skaters have more time to train? Summer school! Some Canadian indoor rinks started to operate all year long.

In the late 1940s, coach Sheldon Galbraith founded a summer skating school in Schumacher, Ontario. Canadian and international champions trained there.

International competitions were often hosted on outdoor rinks. Skating on an outdoor rink posed a unique challenge. Sometimes skaters were blown around the ice by strong winds; the ice surface was uneven, and there was always a risk of frostbite. Canadian and American skaters adapted to these conditions by training on outdoor rinks.

Costume

Women’s Costumes

Female skaters often changed their costumes for figures and free-skating categories. Costumes for figures were one-piece and designed to emphasize grace of movement. Practice dresses were fashioned out of jersey or tight-knit wool.

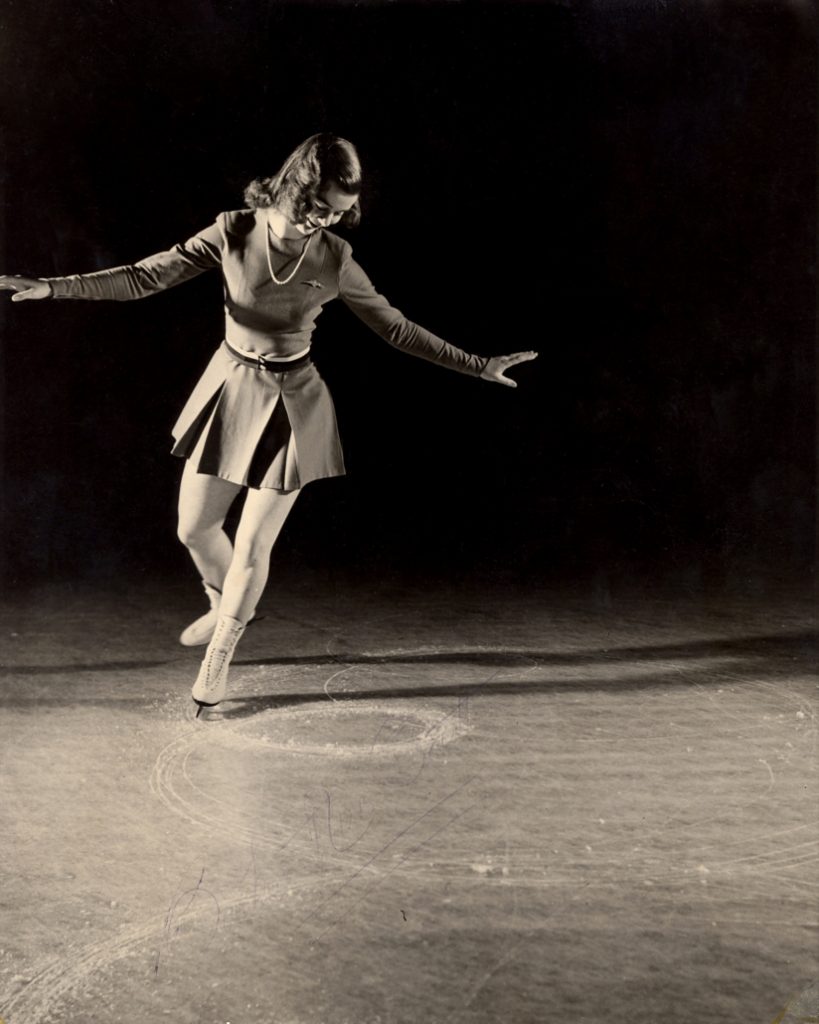

Barbara Ann Scott wearing a pearl necklace and wool skating dress with pleats for figures, 1947-1948. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Competitive free-skating costumes were made of luxurious velvet and chiffon. Smatterings of sequins or delicate beading completed the look.

Stretch jersey was used in skating outfits in the 1950s. Before this, fabrics were non-stretch, and the arms of a skating costume required extra gussets and pleats for ease of movement.

Skating mothers put their sewing and knitting skills to work making their children elaborate costumes for practice and competition. Aileen Wagner, Barbara Wagner’s mother, made all her skating outfits. Material would be bought for Robert Wagner’s skating suits, which were made by a tailor. Aileen Wagner would make Barbara’s dresses from the left over material to match Robert’s outfit. Sometimes figure skaters hired professional dressmakers. In the early 1960s, dressmaking services could be obtained through department stores such as Eaton’s as well.

Barbara Wagner’s grey wool dress made by Aileen Wagner, worn for competitions, 1958-1960. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

After her competitive career, World pair champion Frances Dafoe became a costume designer for skaters and worked at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) designing costumes for television productions.

Frances Dafoe designed skating costumes for herself and Norris Bowden, 1956. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

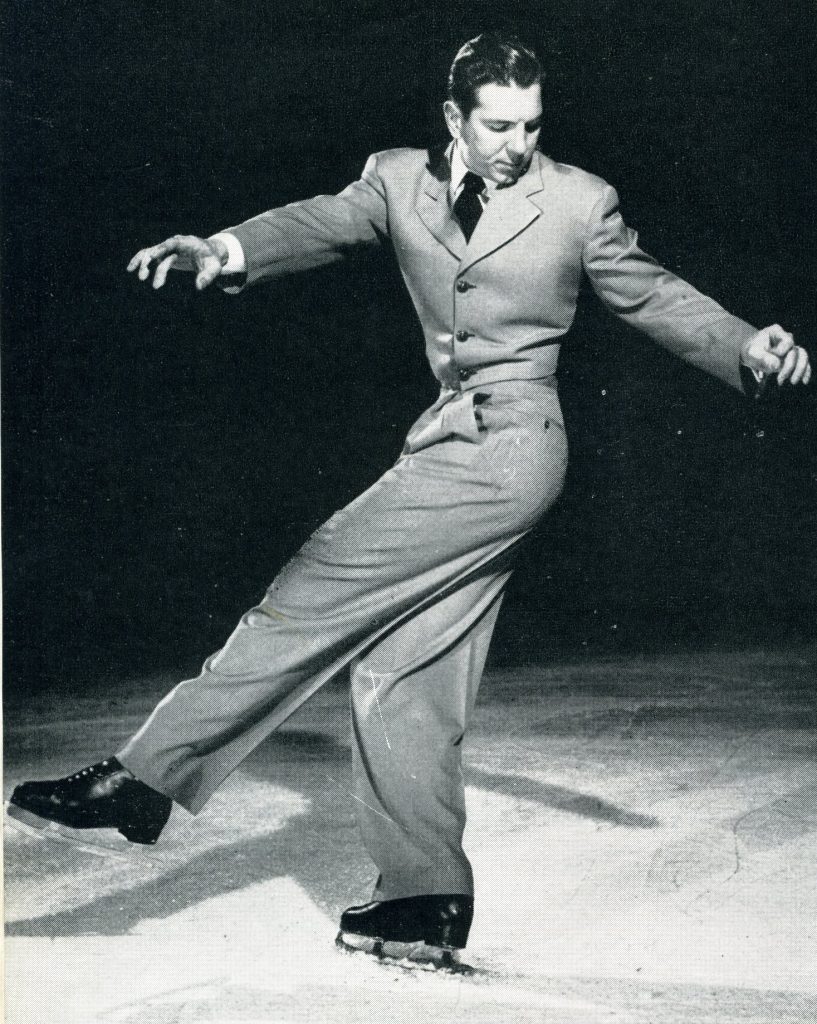

Men’s Costumes

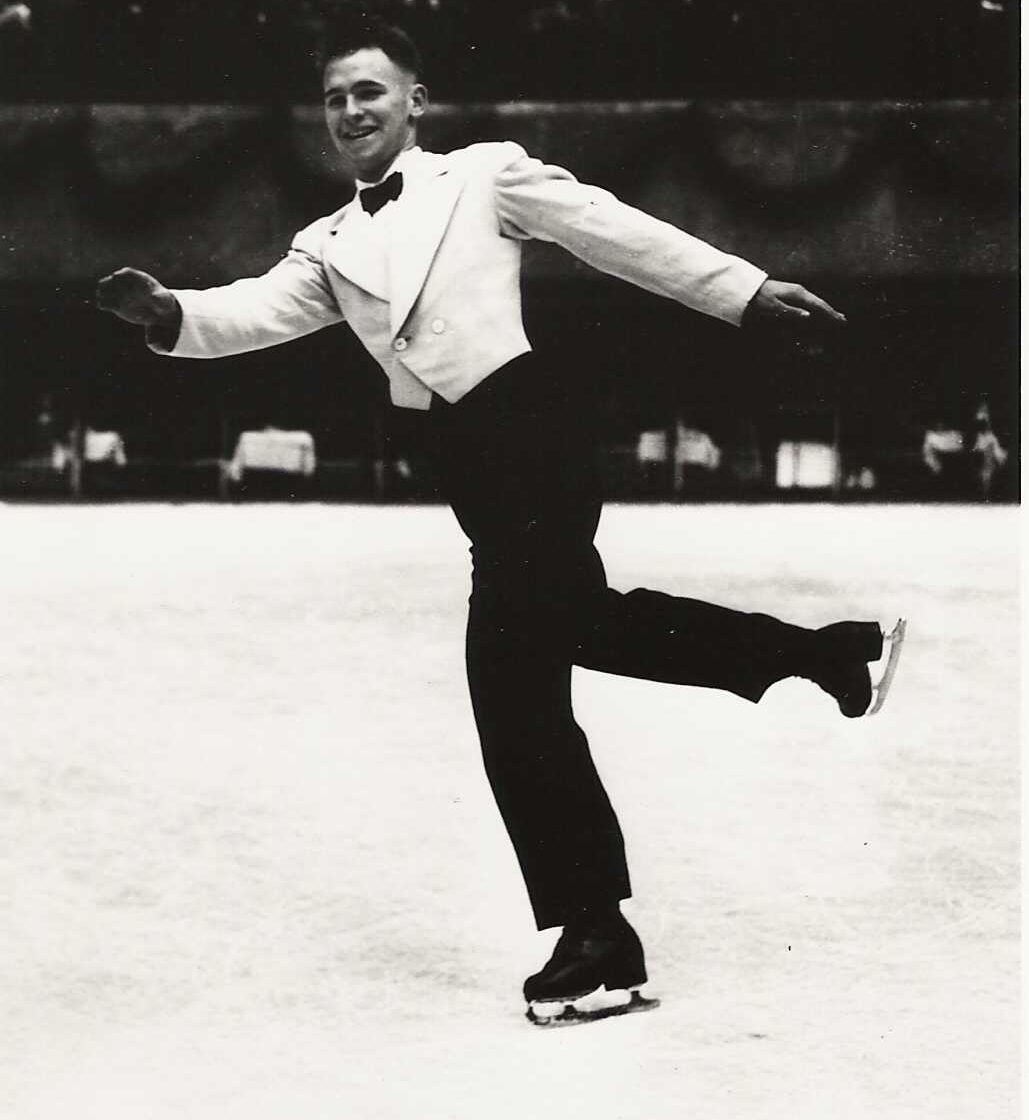

American Dick Button broke with an established tradition of wearing dark colours when he wore a short white waist-jacket on the ice in 1947. This fashion choice soon caught on. These two-piece costumes were not made of knit fabrics, but had many extra gussets and pleats for ease of motion. This style was popular for men into the 1950s.

Charles Snelling wearing a short white waist jacket. Toronto Skating Club Carnival program, 1954. Courtesy Yvonne Butorac

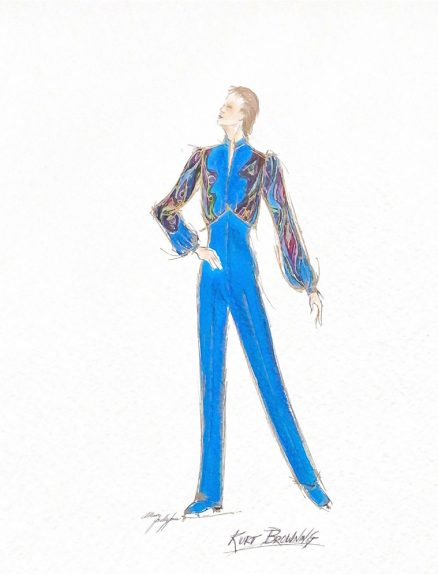

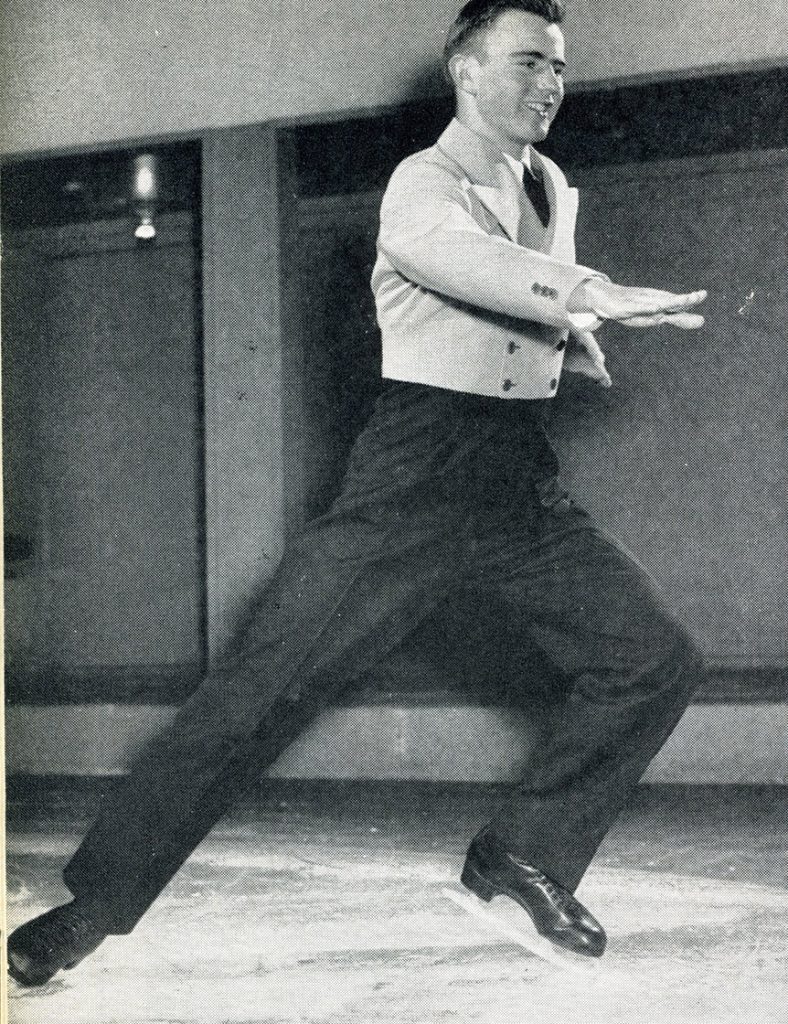

Canadian Donald Jackson became a trendsetter when he stepped onto the ice wearing a stretch one-piece jumpsuit in the late 1950s. Pierre Brunet, Jackson’s coach, took the skater to Paris to outfit him with these new stretchy costumes.

Donald Jackson skating in his one- piece jumpsuit designed in Paris, 1960. Astra Burka Archives

A Forum for Self Expression

Champion skaters joined local talent out on the ice at annual carnivals staged by skating clubs. There were choreographed numbers for children, teenagers, and adults. In the early 1960s, the Rotary Club of Toronto presented its Ice Revue, which featured the best acts from 20 regional skating clubs, with guest performances by Olympic and World medallists. The show packed Maple Leaf Gardens arena.

Barbara Ann Scott in a show costume: sequined dress with feathered skirt, jeweled tiara, and beaded cape with fur trim, c. 1948. © Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

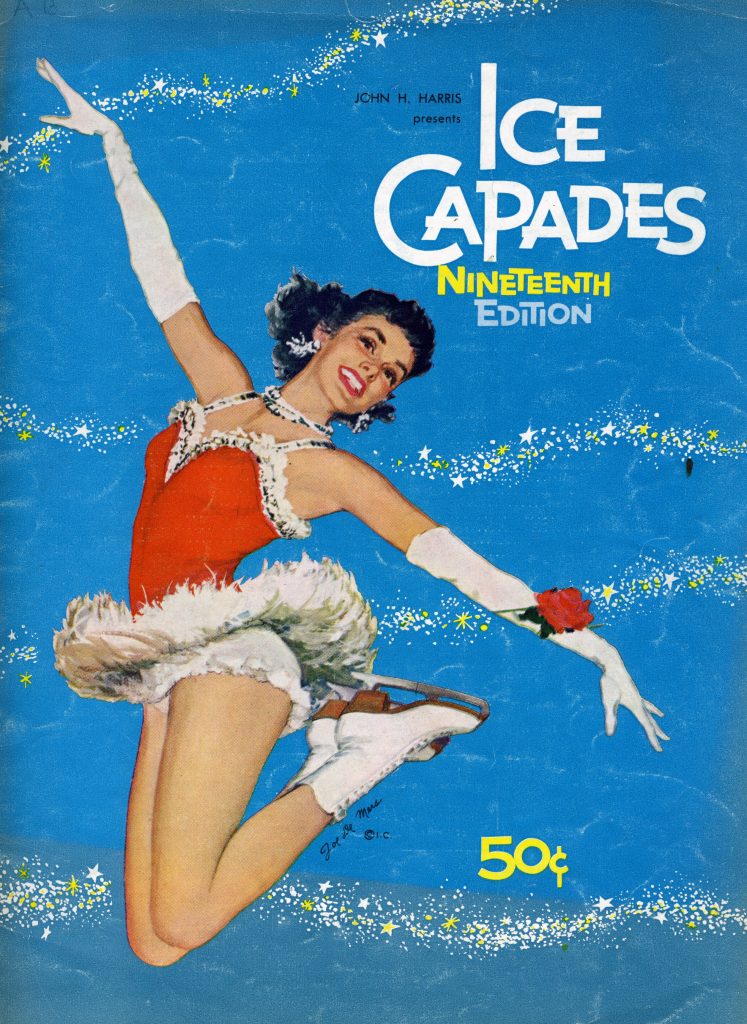

When skaters turned professional, they could earn money by performing in ice shows. Many skaters performed in revues like Holiday on Ice, the Ice Follies, and the Ice Capades. Barbara Ann Scott turned professional in 1948 with her own signature ice revue, Rose Marie on Ice.

Music

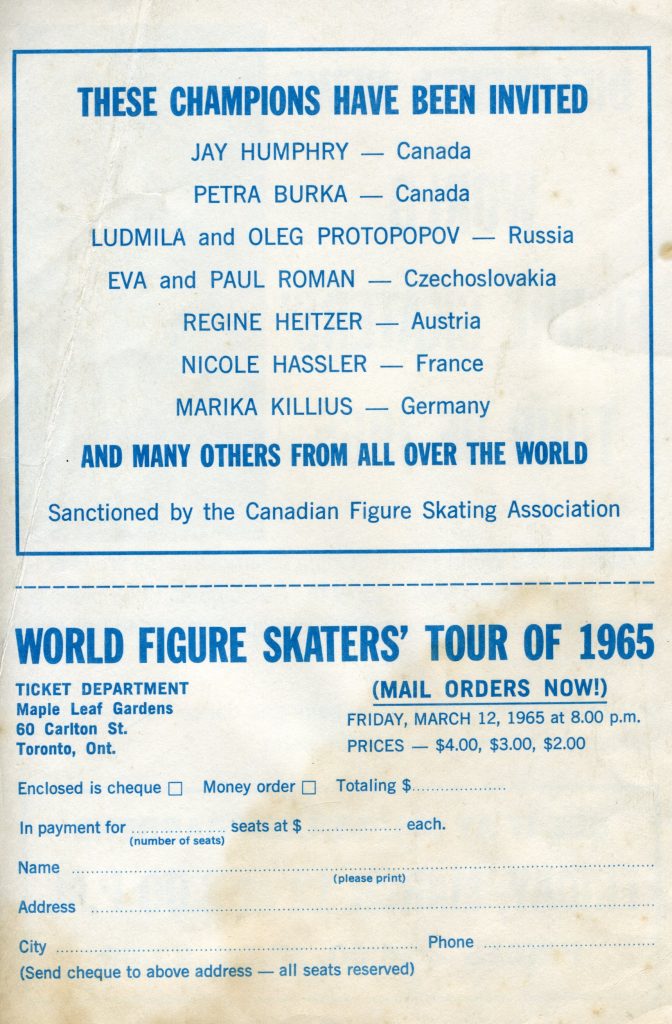

Reel-to-Reel Technology

Sound systems varied in quality from rink to rink. There was not a consistent playback system, and so the sound of the music recording depended on the equipment. The music needed to have the right tempo or the skater’s routine would be either too fast or too slow. Reel-to-reel recordings of the custom-pressed records were therefore sped up or slowed down manually to compensate for the inconsistency.

In the 1950s, Canadian music technician Wilf Langevin began his career playing music for skaters and announcing at Toronto’s Lakeshore Skating Club. He explained:

The era of records created a problem because record players did not necessarily play the same time for the program that the skaters were practising to [on reel-to-reel].

In that case Langevin would have to slow down or speed up the record to reach the proper timing. The right time for the program was accomplished because most of the record players that were used allowed you to change the speed.

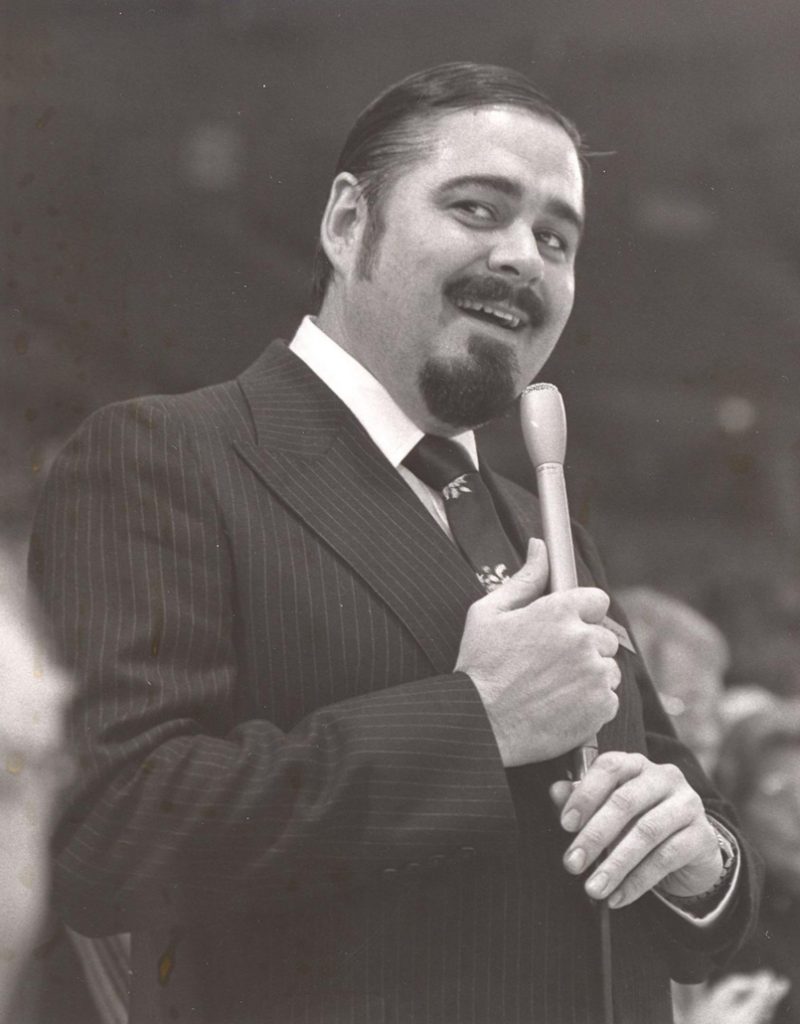

Langevin went on to become an announcer and music co-ordinator at not only Canadian championships but international ones as well, working on the international circuit from 1966 to 1999.

Wilf Langevin with microphone announcing to the audience. © Skate Canada

Music Choices

Singles skaters and pairs teams selected music for their competitive routines. Skating-program music compilations consisted of different pieces of classical music spliced together. The tempo at the beginning and end was usually faster-paced, and the mid-section was slower and smoother. The changes showcased different skating elements within the performance. The compilations were recorded and spliced together on reel-to-reel tape recorders and then pressed into a record. The resulting shellac records were fragile. Skaters had multiple copies made in case any broke or were scratched, and carried them to competitions in special music boxes.

Skaters used more experimental music for their show programs at carnivals and exhibitions. They explored the dramatic possibilities of Broadway show tunes and instrumental film music.

Ice dancing was different. The music was standardized so all skaters performed to the same tune and tempo. Traditional ballroom-dance music selections were played on the organ, and Canadian dancers generally hired Doug Walker, an English organist, to record the standard tunes for each dance. After recording the skating music on reel-to-reel, Walker created a record for the skaters to use at the rink.

For very special occasions, orchestras played live music. For the 1950 World Championships in London, England, all skating competitors submitted their skating-program music records in advance of the competition. A symphony orchestra scored the music and played each competitor’s program live at the competition.

By the 1960s, the organ music was coming to an end for the dance category, and less fragile vinyl records were introduced.