Innovation

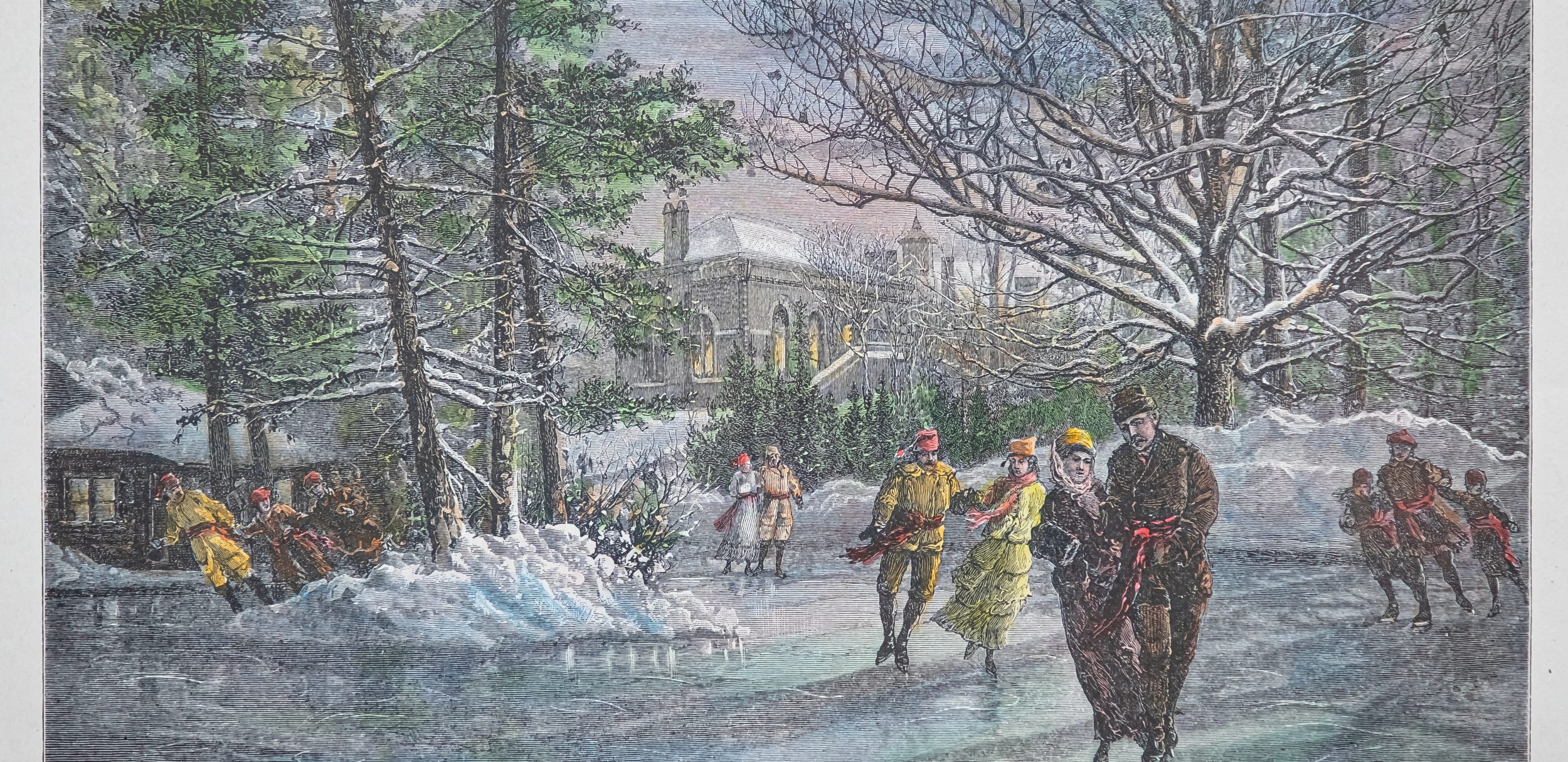

1860

1920

Overview

Leisure skating on Grenadier Pond in High Park, Toronto. Photograph, 1914 John Boyd / Library and Archives Canada

Over the course of the next six decades, from 1860 to 1920, skating evolved from a leisure pastime to an official sport. Canadian innovation played a role in the development of skating blades, movement, covered rinks, rules, and skating carnivals.

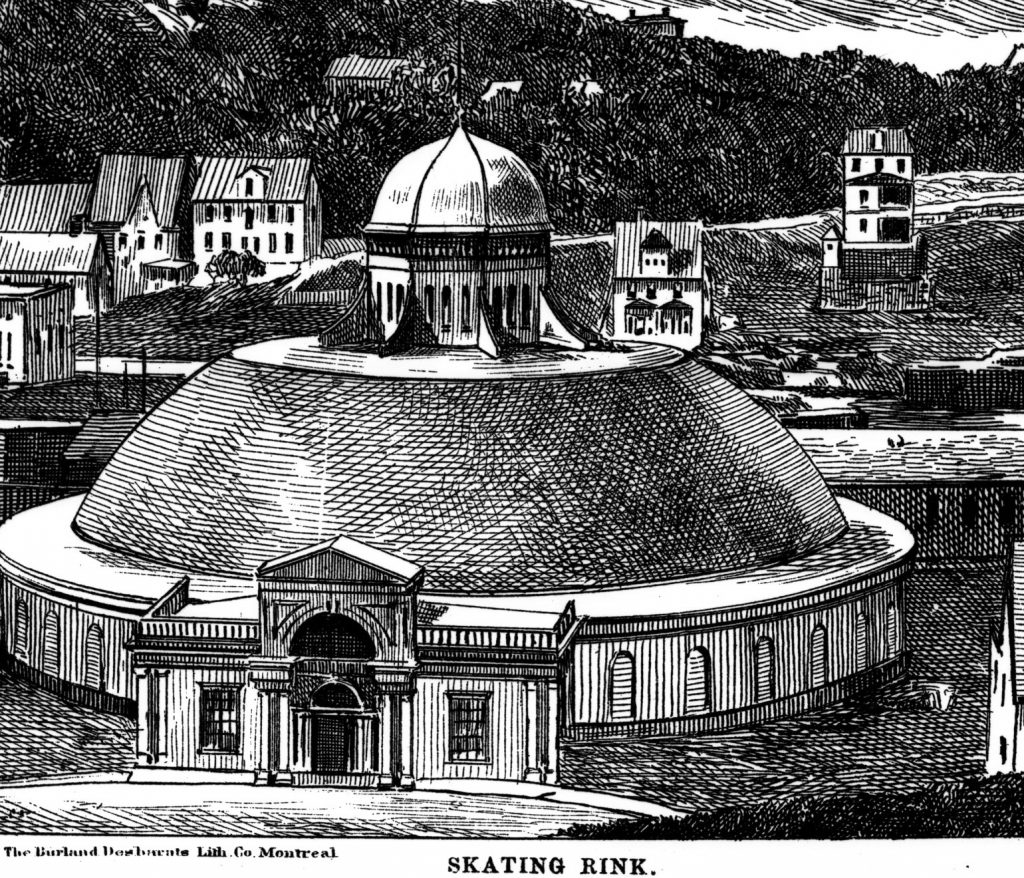

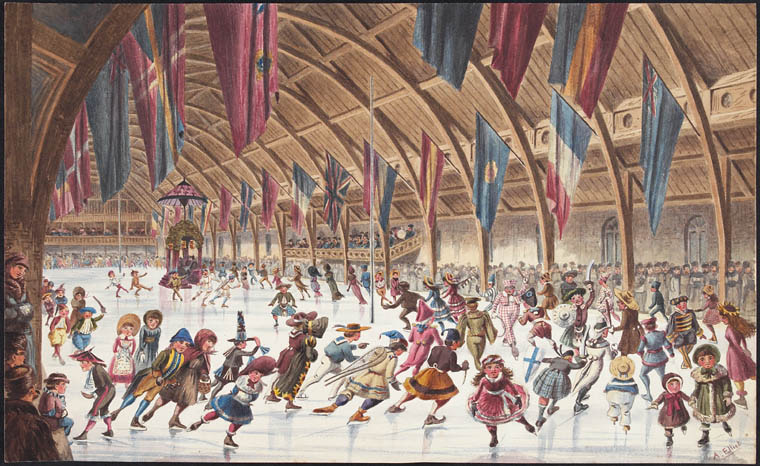

The immense Victoria Skating Rink, Saint John, New Brunswick. Lithograph, c.1880s. ©Provincial Archives of New Brunswick / Archives provincials du Nouveau-Brunswick

This was the era when the Starr Manufacturing Company in Nova Scotia became the first Canadian company to produce clamp-on skate blades.

Starr Manufacturing skate advertisement mentioning figure skating, 1919 ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

The mid-1800s saw new skating ideas develop by way of international exchange. The American skater Jackson Haines introduced a fresh style of artistic skating in his extravagant exhibition performances during the 1860s, which was adapted by Louis Rubenstein, the pioneer of Canadian figure skating.

Masquerade skating carnivals became a popular form of entertainment during wintertime. Many skating clubs began to pop up in cities across Canada, with many outdoor and covered rinks opening over the years.

Skating Carnival, Montreal 1881-1882. Library and Archives Canada (3017363)

Interestingly, in the 1800s, only men competed in competitions. Madge Syers was the first woman to compete in an all-male event at the World Championships in London, in 1902. There was actually no regulation barring women from competing so she did, and won a silver medal. This opened acceptance for women to compete officially at Worlds in 1906 when a women’s singles category was created. Other competitions soon followed suit.

When did figure skating become an official sport in Canada?

When did figure skating become an official sport in Canada?

1887. Louis Rubenstein founded the Amateur Skating Association of Canada, which included figure skating and speed skating.

Boots & Blades

Made in Canada

Starr Manufacturing plant in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, photograph c.1890-1910. ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

Early strap-on skate by Starr Manufacturing (est. 1861), Nova Scotia c. 1863. ©Bata Shoe Museum, S82.313

The Starr Manufacturing Company opened its doors in 1861; the business was started by John Starr of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. John Forbes, a foreman and inventor at the company, worked together with fellow Starr employee Thomas Bateman to design a new clamp-on blade. The Acme Spring Skate debuted in 1863 revolutionizing the design of blades in Canada. Nicknamed the “Halifax” skate, it achieved world-wide popularity.

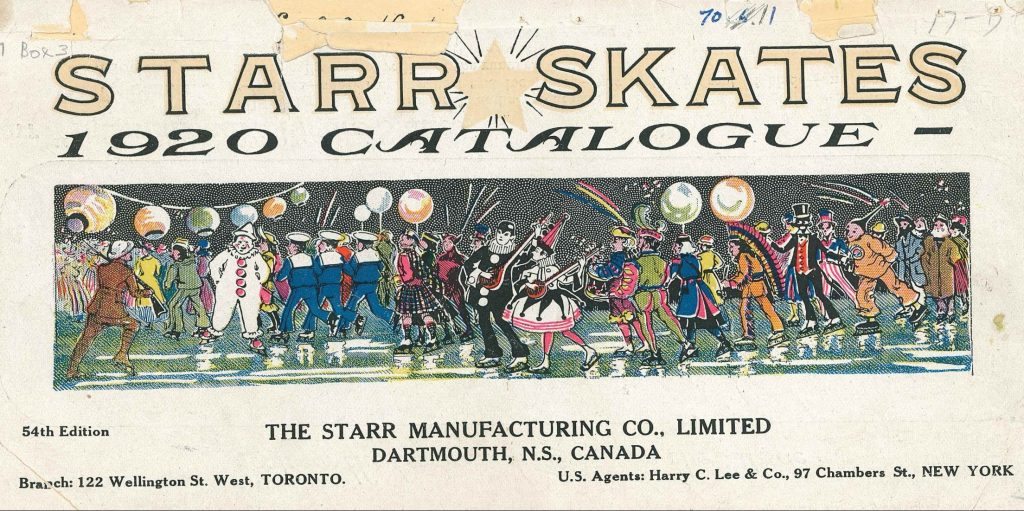

Cover of the Starr Skates Catalogue, 54th edition, 1920. ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

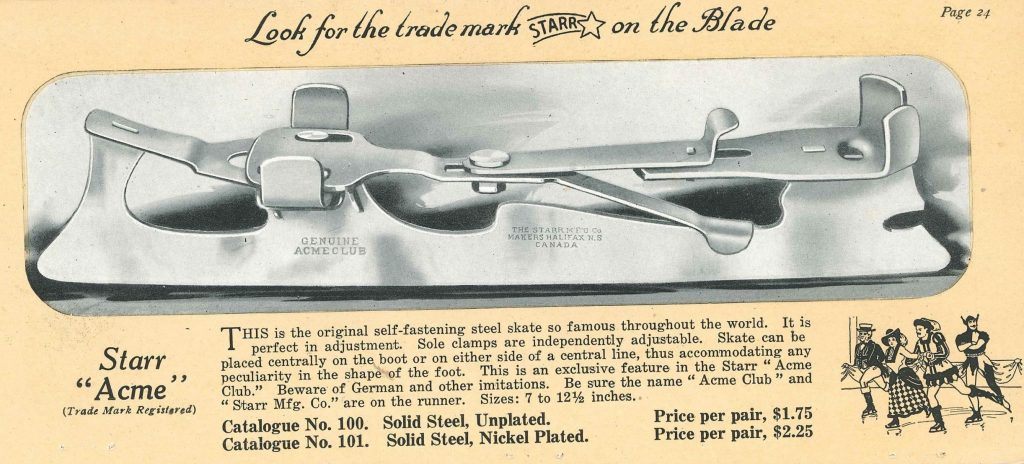

Starr Manufacturing Company Sales Catalogue of 1920, showing that the original Starr “Acme” Club blades are still being sold, page 24. ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

What made the Acme Spring Skate so innovative? The clamp-on idea was not new, but the Acme clamp-on blades were designed with a mechanism that would spring-lock onto a skater’s boots. The Spring Skates were an improvement over other clamp-on styles, and a vast improvement over older skates that were attached to a skater’s boot by way of straps, which had the habit of falling off or breaking.

Starr Acme Club “Spring” skate blade c. 1864 ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

Starr Manufacturing would go on to sell 11 million Spring Skates up until its skate department closed in 1939.

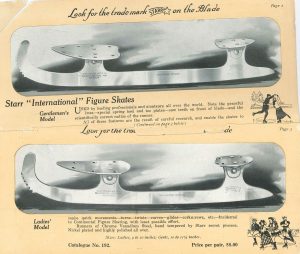

Starr “International” figure skates, pages 2 and 3 of the Starr Skates Catalogue, 1920. ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

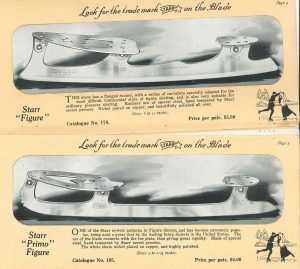

“Figure” and “Primo” figure blades, pages 4 and 5 of the Starr Skates Catalogue, 1920. ©Dartmouth Heritage Museum

Scroll across the screen here to see Starr skate blades:

Boot construction for skates is poorly documented in the 1800s. There were no specific skating boots at the time; people used their own all-purpose boots. What we do know is that boot makers began to make special boots to accommodate the Acme Spring Skate.

By 1900, blade design improved in that blades could now be attached to the base of a boot, either by screws or by using the Acme spring technology.

Scroll across the screen here to see different versions of skate blades that the Starr company produced over the years. Courtesy of the Dartmouth Heritage Museum:

Other Skate Manufacturers in North America and Europe

As the sport of figure skating developed, so too did the design of blades across the rest of North America and Europe. The period saw the innovation of blade design transition from clamp-on to an upturned-toe blade, to a one-piece blade.

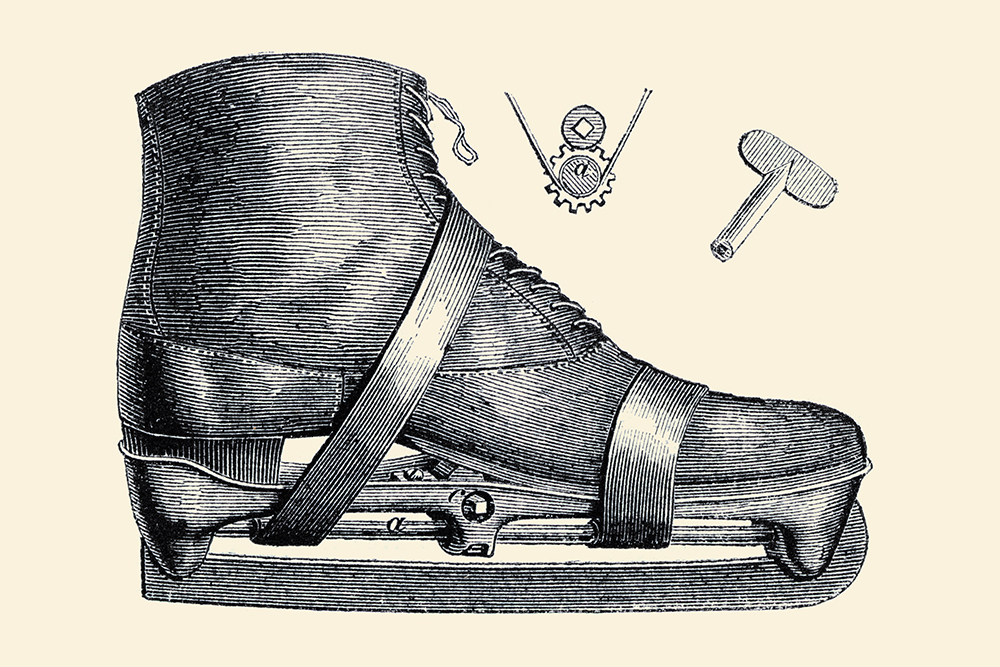

In 1848, the American firm E.V. Bushnell was the first to invent an all-steel clamp, allowing blades to be attached to boots. In 1865, American skater Jackson Haines developed a two-plate, all-metal blade that could be attached directly to his boots. He also invented the toe pick in 1870.

Bushnell’s later invention, the key-wound ice skate, circa 1883. © Buyenlarge/Getty Images

In 1876, A.G. Spalding & Brothers developed an upturned-toe blade model for skating. The blade was manufactured in the USA and available in Canada.

‘Continental’ model blades by A.G. Spalding & Bros., Chicago, Illinois. The boots are the ‘Duluth Hockey Shoe’ model, by Northern Shoe Co., Minnesota, c.1906-1918. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, 2019.51

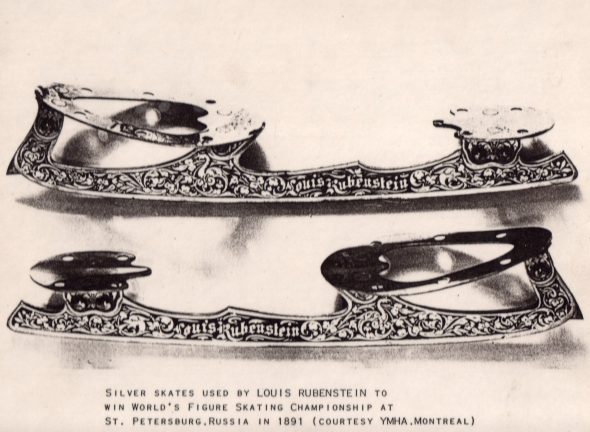

By 1879, Barney and Berry’s in Springfield, Massachusetts, had a catalogue with a variety of skate options, which Canadians could purchase. They were the ones who made Louis Rubenstein’s custom blades.

Barney and Berry silver-plated skates worn by Louis Rubenstein at World's Figure Skating Championship, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1891. Courtesy of Rubenstein RB Digital Inc. and Hillel Becker

1888 saw the advent of the John E. Strauss blade; Strauss, a locksmith and metalworker from Minneapolis, turned his skills toward skate production. He created a closed-toe blade made from a single piece of steel, making skates lighter and stronger.

John Strauss making a custom figure blade, 1919. Courtesy of Strauss Skates and Bicycles

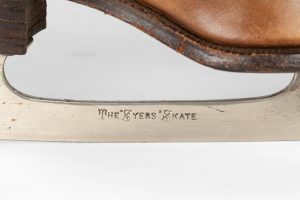

English boot and blade example: Boot made by “The Lobby Shoe” and the blade named “The Syers Skate” by John Wilson, Sheffield, after the first woman World Champion.

John Wilson’s “The Syers Skate” blade was named after Madge Syers, the first women’s world champion, 1906. The boots are a product of “The Lobby Shoes” company. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S86.163

Detail of the blade named after English skater Madge Syers. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, S86.163

North American, English, and European wooden platforms with blades. These wooden platform blades were popular in Canada until about 1900 and in Europe until the mid-1900s.

These blades have a swan’s shape hand chiseled into the toe curl. Possibly German, c 1900. Collection of the Bata Shoe Museum, P85.0050

Madge Syers and Women’s Liberation in Skating

At the turn of the 20th century, women were not allowed to participate in international competitions. One skater, Madge Syers, made history as the first woman to compete at the World Championships in 1902, in a previously all-male event. She won a silver medal. Syers would go on to be the first woman to win the Worlds in 1906 and the Olympics in 1908. Her contributions to the sport gave women the opportunity to participate fully in figure skating.

Scroll across the screen here to see examples of wooden platform skates held in the Bata Shoe Museum Collection:

What was the most popular name for a skating rink in the 1800s?

What was the most popular name for a skating rink in the 1800s?

Victoria, after Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria loved skating, and many skating rinks across Canada were named in her honour.

Movement

Pioneer of Canadian Figure Skating

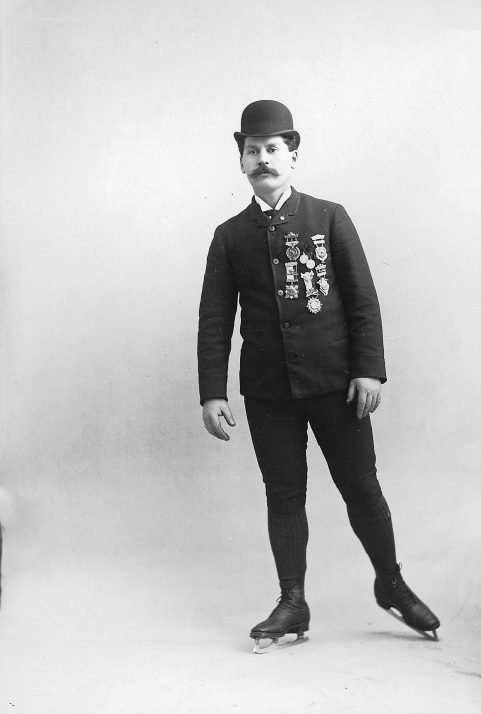

Canadian Louis Rubenstein was a pioneer in the sport known as fancy skating, which predated figure skating. He was chosen to represent Canada in the 1890 international competition—the precursor to the World Championship—in Russia. In the late 1800s, Czarist Russia was deeply anti-Semitic. When Rubenstein arrived in Russia to compete, the police confiscated his passport. He was told that he had to leave the country within 24 hours.

Louis Rubenstein in Montreal, Quebec, 1893 © McCord Museum

Rubenstein and the Canadian government had anticipated such troubles. Rubinstein presented a letter written by Lord Stanley, then Governor General of Canada, to the British Embassy. Under pressure from the British Embassy, the police returned Rubenstein’s passport, and he was allowed to compete. Rubenstein won gold at the competition. Regardless, afterwards he was told to leave Russia immediately.

Rubenstein was a devotee of the Jackson Haines method of skating, which gave free skating a more prominent place in competitions. He founded the Figure Skating Department of the Amateur Skating Association of Canada in 1914 and served as the organization’s president until 1930.

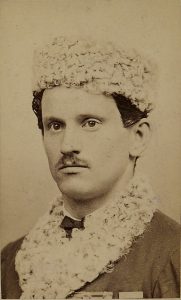

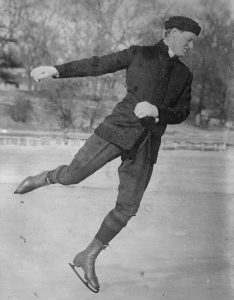

Jackson Haines (1840-1875), the “Pioneer of Artistic Skating”

American skater and ballet dancer Jackson Haines performed in Canada during the early 1860s. He showcased his unique style of free skating that blended skating movements with balletic elements. Audiences loved his theatrical flair, and he would go on to influence the next generation of Canadian skaters.

Haines travelled to Europe in 1864 to demonstrate his new skating style. He was a beloved figure in Vienna, where he skated to the music of Mozart, Schubert and Johann Strauss before captivated crowds.

Haines blended the technical prowess and artistry of free skating with musicality and gave music a more prominent place in skating programs. He died tragically young at the age of 36 after contracting tuberculosis and pneumonia.

Skating Movement Innovation

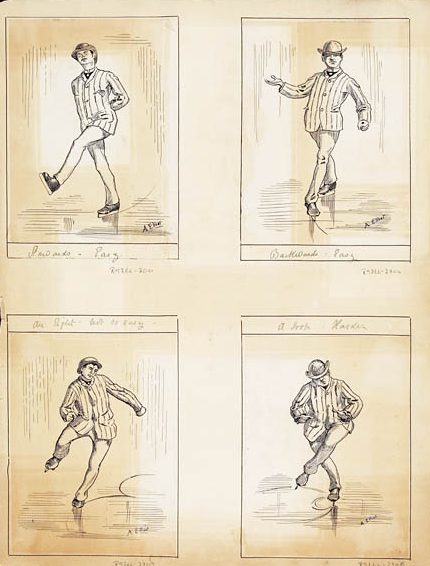

Artistic movements on ice developed out of the fundamental movements of forwards and backwards skating and the sweeping edge rolls done in both directions that were leisure-skating moves of earlier times. In the 1860s, fancy skating and continuous skating emerged as two distinct styles.

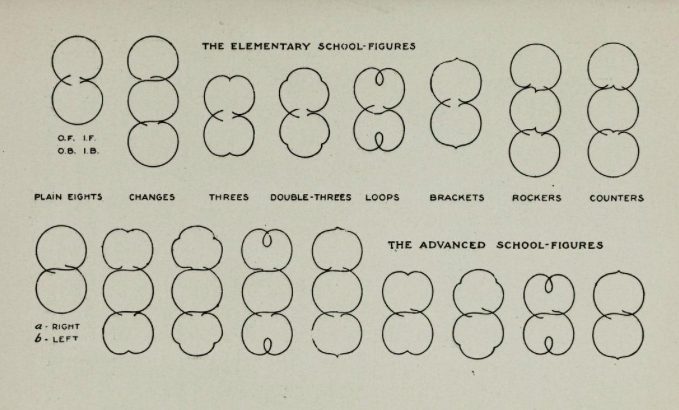

Four illustrations of skating moves by Arthur Elliot, c. 1882. Collection of Library and Archives Canada (R9266)

Both styles were based on controlled patterns that the skater would “draw” into the ice. Figure skating derives its name from these patterns (or figures) that were made in the ice. The establishment of these styles meant that skaters could be judged on their talent in creating such figures, and skating competitions became popular.

Skating in pairs, known as combination skating, also developed during this time. All three styles were popular until the end of the 1800s.

Fancy Skating

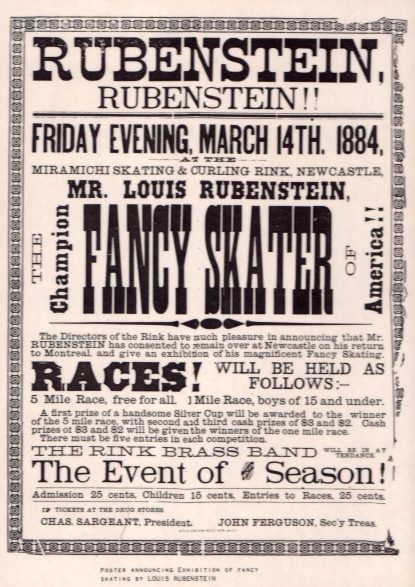

Fancy skating, which was first noted as a term in the 1850s, referred to any type of skating that involved more than the most basic gliding and pushing forwards on the right, and then to the left, edge (i.e., the Dutch Roll). Louis Rubenstein was Canada’s champion fancy skater.

Fancy Skating poster starring Champion Louis Rubenstein, 1884. Courtesy of Rubenstein RB Digital Inc. and Hillel Becker

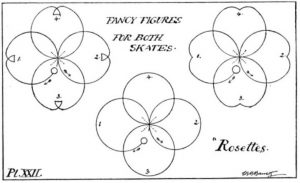

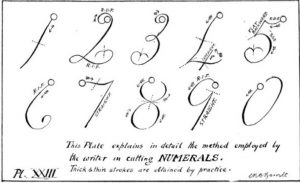

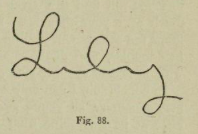

Circular geometric shapes (often figure eights), turns of many types (such as three-turns, brackets, rockers, counters, and loops), spins, and even jumps were all part of fancy skating. The style consisted of criss-crossing, exquisite patterns that the skater carefully traced into the ice while gliding on one foot. Rosettes, stars, crosses, curlicues, and even letters and numbers were popular.

Fancy figure patterns to trace into the ice. From Figure and Fancy Skating by George Meagher, London, 1895.

Patterns showing how to cut fancy numbers in to the ice. From Figure and Fancy Skating by George Meagher, London, 1895.

To watch skaters perform such detailed moves would have been quite a treat. The result was an intricately cut pattern on the ice like the effect of cut crystal. Skaters who created the best tracings displayed exceptional balance, precision, and control.

“Lily” Cheetham, an English skater, traced her name on ice. From Skating by Douglas Adams and Lily Cheetham, London, 1892.

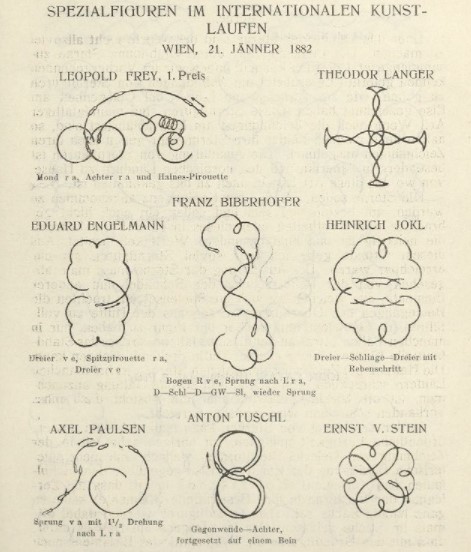

The early versions of these moves were really just parts of what we think of today as free skating. Competitive free-skating performances were very short. In Vienna in 1882, Norwegian Axel Paulsen debuted his controversial new jump in an international competition. The performance was perhaps only 10 seconds long! His performance entailed just five steps and the jump itself. The judges were accustomed to competitors tracing short but difficult patterns into the ice, and Paulsen’s Axel jump was a completely new element. He won third place.

Winners of 1882 Great International Skating Tournament, Vienna In Dr. Gilbert Fuchs Theorie und Praxis des Kunstlaufes am Eise, 1926.

As was the case with the Axel jump, new moves were often named after the move’s creators. For instance, the Salchow jump, where a skater takes off on a back inside edge and lands on the back outside edge, was named for Swedish skater Ulrich Salchow.

Although jumping is something skating spectators love to watch, in the 1800s jumping was only just being added to skaters’ repertoires. It was practiced solely by men until the 1920s, when women began to introduce jumps into their skating programs.

In 1890, fancy skating was replaced by compulsory (school) figures. Compulsory figures were standard movements done in a figure eight in groups of two and three circles. Three-turns, brackets, rockers, counters, and loops demanded that skater turn front to back, or back to front, while balancing on the one skating foot. The figure eights were skated alternately on the left and right foot.

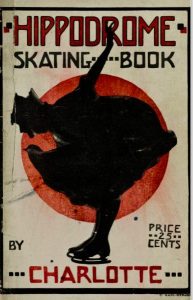

Patterns used in the Elementary and Advanced Compulsory Figure Tests. Hippodrome Skating Book by Charlotte Oelschlägel, 1916.

Continuous Skating

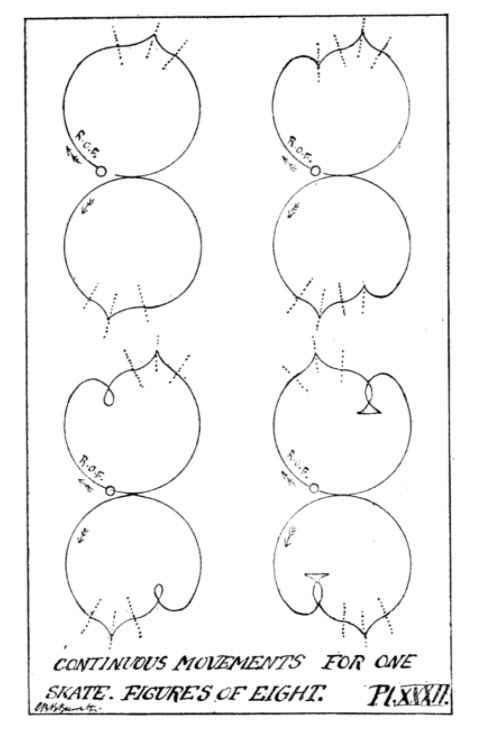

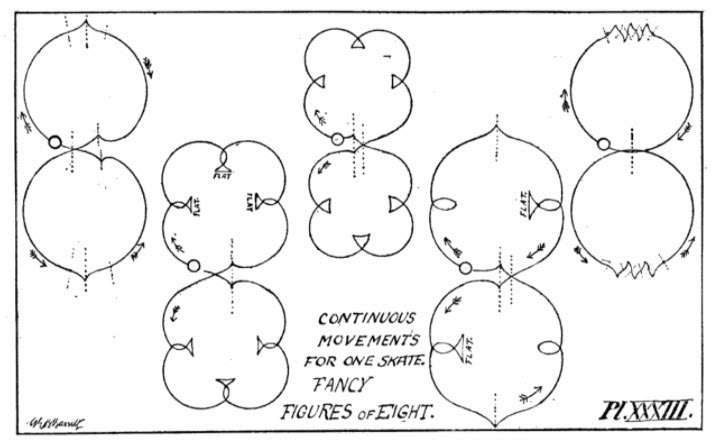

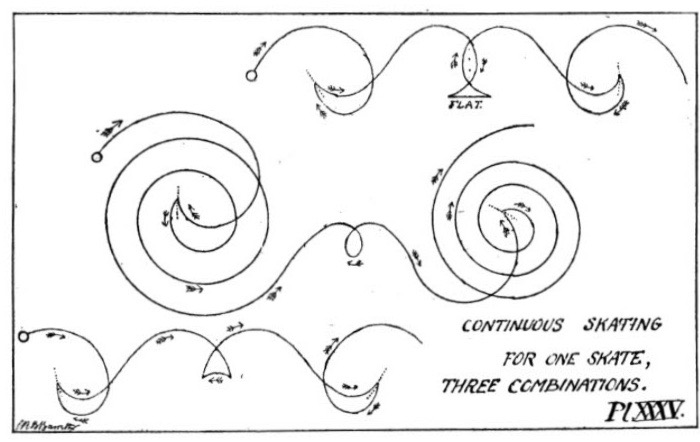

Continuous skating patterns to be completed on one foot only. From Figure and Fancy Skating by George Meagher, London, 1895.

Can you imagine performing a skating program on a single foot? In continuous skating, skaters were challenged to trace complex figures, but only on one foot. Skaters had to propel themselves by gaining speed with each turn and loop. They used jerking movements and assumed ungraceful postures to balance without ever stepping down with their free foot. Popular figures included continuous figure eights, a movement known as “the frame”, grapevines, and serpentines. Continuous skating programs were often set to music.

Combined Skating

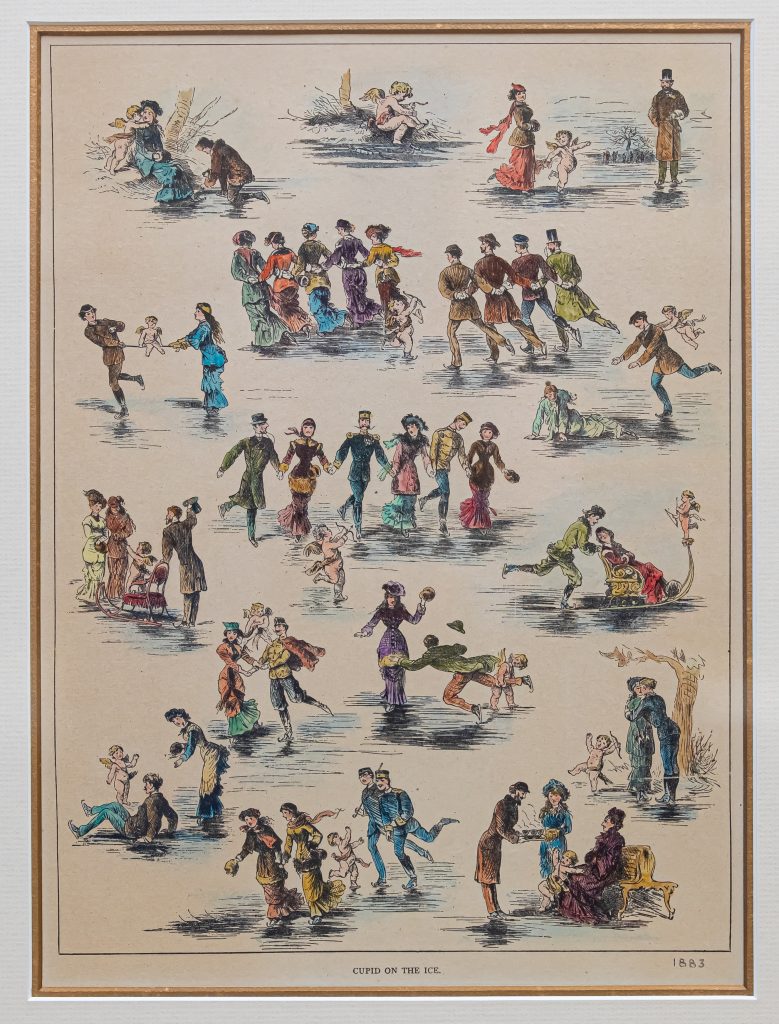

Combined skating dates back to the 1700s and was practiced in both Europe and North America. Other terms used for combined skating were shadow, side-by-side, or hand-in-hand skating. It involved two, or even more, people doing moves that single skaters could do alone. In Canada, couples performed waltzes and quadrilles with musical accompaniment.

Cupid on the Ice, coloured lithograph, c. 1883. ©Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

Although it is difficult to trace the complete history of ice dancing, the form seems to have sprung up out of combined skating. Ice dancing’s popularity dates as far back as the 1880s in Vienna. In Canada, the waltz was danced on ice in Halifax in 1885. Ice dancers drew inspiration from ballroom dancing, replicating dance steps on the ice while combining them with free-skating figures to create a graceful new form. Many ice dances have a long history. The Fourteen Step and the Kilian were developed in Vienna in 1889 and 1909, respectively. The European Waltz was created sometime before 1900.

Combined skating at Rideau Hall, Ottawa, Ontario, c. 1915. Collection of Basil Reid/Library and Archives Canada (PA-030205)

Combined Pairs skating at Rideau Hall, Ottawa, Ontario. March, 1911. Collection of William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada (3386286)

First Canadian Skater to Write a Book on Skating

George Meagher, Canadian figure skating pioneer. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

George Meagher was a Canadian star skater in the 1800s. Meagher won the Amateur Championship of the World in 1891 and later the Professional Championship of the World in 1898. He introduced the Canadian sport of ice hockey to Europe while on a skating trip to Paris in 1894. Like his American counterpart Jackson Haines, he gave professional performances of fancy skating throughout North America and Europe. Contemporary media accounts raved about his skating talents: “he can do twenty-three different grapevines, fourteen spins and seventy-four figure eights, and over one hundred anvils on one foot without stopping.”

His 1895 book, Figure and Fancy Skating describes in detail compulsory and special figures, skates, and elements of jumping, spinning, and waltzes. Meagher would go on to pen two more skating books: Lessons in Skating in 1900 and A Guide to Artistic Skating in 1919.

Irving Brokaw

Two British skating manuals were considered foundational texts for Canadian figure skaters in the mid-1800s. The Art of Skating was written by George Anderson, using the pen name Cyclos, in 1852. A System of Figure Skating by H.E. Vandervell and T. Maxwell Witham came later, in 1869.

Perhaps the most influential North American writer on skating in this period was champion figure skater Irving Brokaw. He published The Art of Skating in 1910. His book illustrated figures and free-style skating, discussing all aspects of competitions. He would later update his book in the 1920s to suit current trends in the sport.

When and where was the first covered artificial ice rink built in Canada?

When and where was the first covered artificial ice rink built in Canada?

The first covered artificial ice rink, Shea’s Amphitheatre, also known as the Winnipeg Amphitheatre, was built in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 1909.

Open Air to Covered Shed Rinks

Government House From Skating Pond, coloured lithograph, c.1882. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

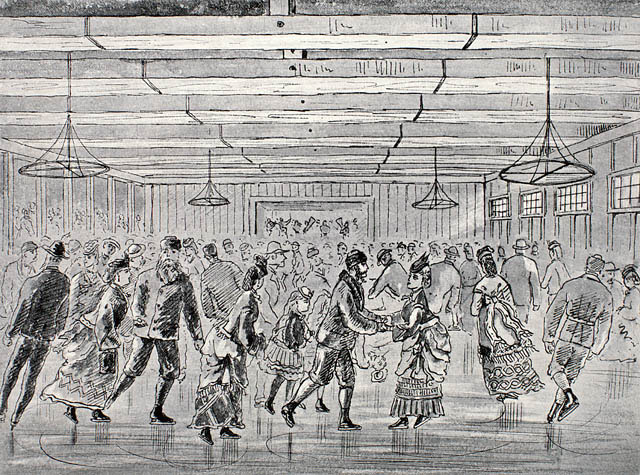

In the late 1800s, much like today, most skating clubs shared space in covered sheds with curling and ice-hockey teams. Frozen ponds, lakes, and open-air rinks were converted into incredible structures that allowed for three months of skating during the entire winter season.

Outdoor skating at Rideau Hall, Ottawa, Ontario. Photograph, 1911. Collection of Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada (PA-043083)

Covered artificial rinks soon sprang up across Canada. The earliest covered shed rink in the world was built in Quebec City in 1852.

The earliest covered shed rink, Quebec City, Quebec. Skating Rink at Quebec, Canadian Scenes No. 4, sketch. Collection of Library and Archives Canada (R9266)

The Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal followed in 1862.

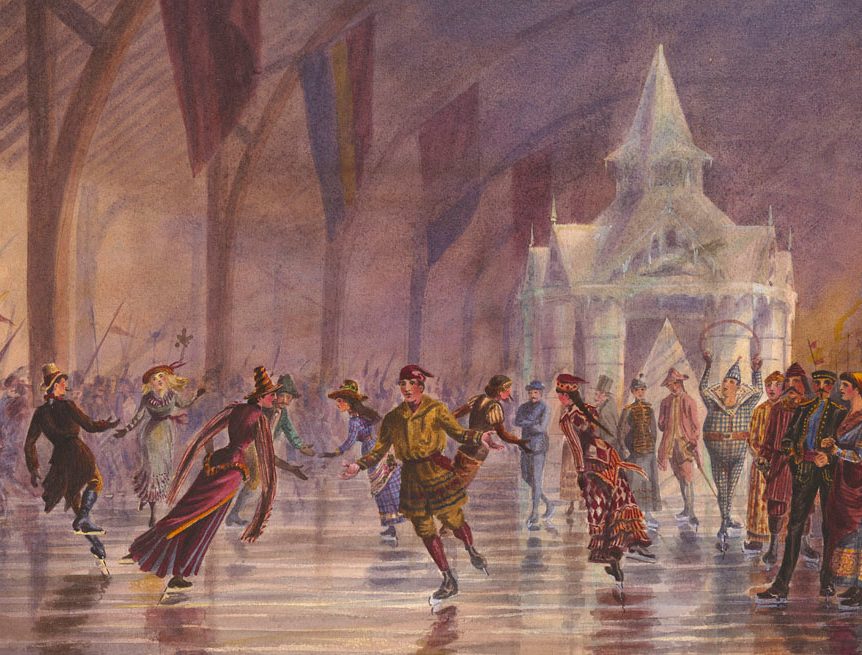

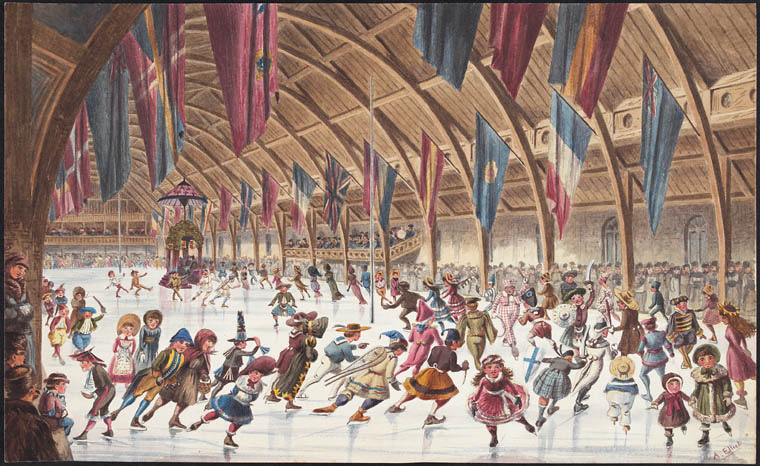

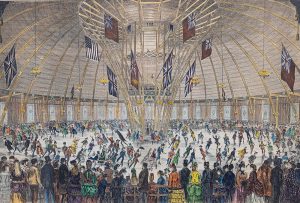

Skating Carnival at the Victoria Rink, Montreal, c. 1881. Collection of Library and Archives Canada (R9266)

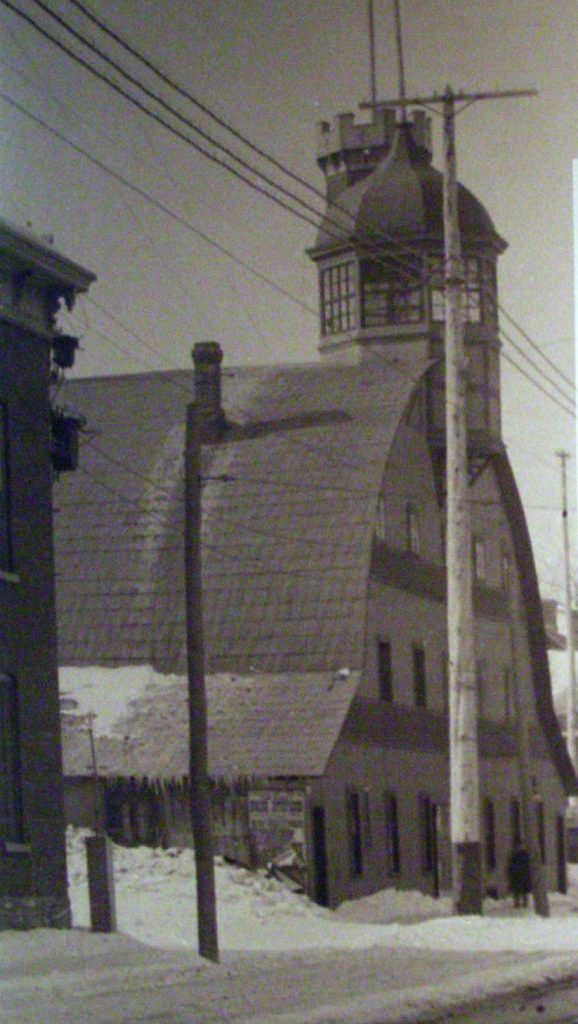

The immense Victoria Skating Rink in Saint John, New Brunswick, built in 1864 by architect Charles Walker, was 50 metres in diameter and 24 metres tall. It was used as a skating facility for 37 years.

Victoria Skating Rink, Saint John, New Brunswick, photograph, c.1870. ©Provincial Archives of New Brunswick / Archives provincials du Nouveau-Brunswick

Musicians play on an elevated platform in the central mushroom column during the 1872 Grand Fancy Ball at the Victoria Rink, Saint John, New Brunswick, by E.J. Russell. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

The Rideau Skating Rink in Ottawa was built in 1889 and housed curling, hockey, and skating clubs. In 1904, the Minto Skating Club used the Rideau facilities, holding several Canadian championships at the Rideau rink until they found their own facility in 1922.

Rideau Skating Rink, Ottawa, Ontario, photograph, c.1904, built in 1889. Alaney2k, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (LAC PA-042365)

Costume

Victorian and Edwardian Skating Wear

Skating on the St. Lawrence in Quebec City (Patinage sur le Saint-Laurent, à Québec), lithograph, 1896. Collection of W.H. Cloverdale / Library and Archives Canada (1970-188-1668)

Victorian and Edwardian-era fashion influenced attire on the ice.

Men’s skating costumes were quite dapper. Men were expected to wear jackets with collars, neckties, and hats. In the 1880s, men decided to wear knitted tights so that the judges could more easily see their footwork. In the late 1800s, men wore casual jackets, although they were still expected to wear neckties and collars. Men eventually wore shorter pants, called knickerbockers, instead of full-length trousers, as well as wool tights and shorter jackets to allow for ease of movement when free skating.

Lady Melgund and Lady Florence on the skating rink at Rideau Hall, photograph, 1884. Collection of Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada (PA-033917)

For women, skirt lengths were regulated by the acceptable norms during the Victorian and Edwardian periods, both on and off the ice. Women’s movements were restricted by the weight and length of petticoats and skirts. For women, the length of skirts required by society’s dress codes of modesty meant they had to wear skirts that went to the floor. On ice, these skirts almost completely covered the skater’s foot movements.

It was Madge Syers in 1902 who dared to shorten her skirt several centimetres, allowing her boots to be seen when she skated figures. With this small change, more movement was possible and the dangers of tripping on one’s skirts were reduced.

In his book Ice Skating, T. D. Richardson wrote about women’s attire in this period:

“The ladies wore beautifully cut black cloth skirts reaching to the top of the shining black boots. Now and again there was a glimpse of coloured lining or petticoat or – very daring – sleek black silk stockings.”

Skating at Rideau Hall, photograph, 1911. Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada (PA-043085)

It was not until the 1920s that society’s idea of modesty started to change, and women could shorten their skirts a bit more.

H.R.H. Princess Patricia and Major Worthington skating on the rink at Rideau Hall, photograph, 1914. Library and Archives Canada / PA-164606

Pre-media Entertainment: Carnivals and Spectacles on Ice

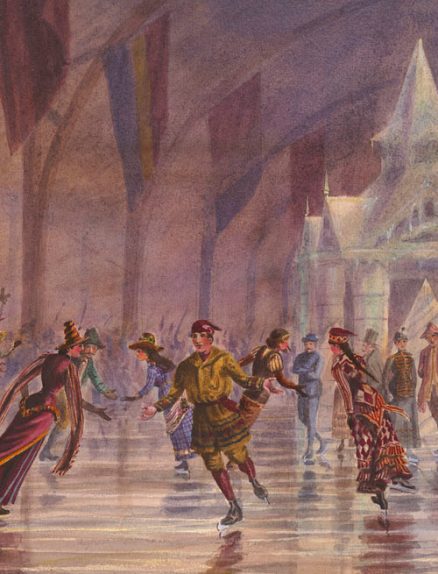

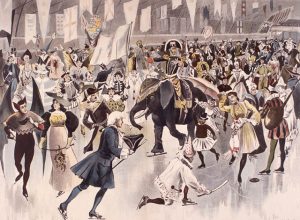

Imagine a group of people skating around in glittering masks and colourful costumes. Skating carnivals were a popular form of entertainment in the 1800s. Prior to 1920, carnivals were elaborate masquerade balls. People skated around maypoles, often dressed in wonderfully extravagant costumes; one could see court jesters, medieval troubadours, and clowns out on the ice.

Winter Life in Canada – A Skating Carnival at Ottawa, lithograph by Arthur Hopkins, c. 1882. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

Masquerade at the Rideau Rink, Ottawa Carnival, 1885. Library and Archives Canada (C-098712)

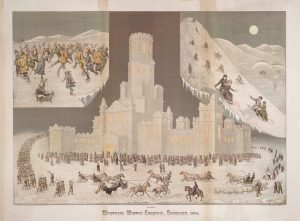

Montreal Winter Carnival, lithograph, February 1884. Library and Archives Canada (Acc. No. R9266-1355)

Fancy Dress Skating Carnival at Montreal, illustration, 1881. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. R9266-218 Peter Winkworth Collection of Canadiana

Stitching together over 300 individual photographs, Scottish-Canadian photographer William Notman captured the glorious fun of a skating carnival in the first composite photograph in 1870. The skating carnival, held at the Victoria Rink in Montreal, was attended by Queen Victoria’s son Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn. Notman captured hundreds of individuals dressed in costumes and military dress in a grand covered rink decorated with evergreen boughs and flags.

Skating Carnival Victoria Rink, composite photography by William Notman, 1870. Courtesy Musée McCord Museum

Charlotte : Ballet on Ice

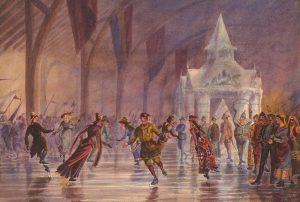

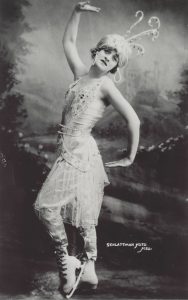

The German figure skater Charlotte Oelschlägel came to America to show off her artistic style of skating. A skating celebrity, she was dubbed “Anna Pavlova on Ice”. She used her first name as her stage name.

In 1915, Charlotte was invited to New York City to perform at a 5,200-seat hippodrome in an ice show called “Flirting in St. Moritz” created by Albert Ernst. Her subsequent handbook, The Hippodrome Skating Book, describes compulsory figures, skating movements, skates, and costumes.

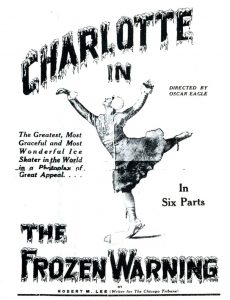

Charlotte: Skating Film

She appeared in the first film featuring figure skating: The Frozen Warning, directed by Oscar Eagle in 1917. Playing herself in this tale of international espionage, Charlotte informs the main character, Lieutenant Vane, of a spy’s intent to steal plans for a sub-sea gun while the two are at a skating party together.

Carnivals were attended by a rapt audience who flocked to watch such amazing spectacles. Skating personalities Jackson Haines and Charlotte Oelschlägel propelled carnivals to popularity.

Jackson Haines, Vienna, c.1867. ©World Figure Skating Museum

Charlotte Oelschlägel, c.1916. ©World Figure Skating Museum

Music

Skating Music

Skating indoors with a band playing at the far end of the rink, 1873. Carlile and Martindale collection / Library and Archives Canada

Jackson Haines used music to enhance his skating programs. Background music played by military bands was part of the attraction for leisure skaters.

Soon, however, music played by military bands or orchestras was incorporated into competitions and carnivals. Marches, waltzes, and mazurkas proved popular. All of these musical forms have a precise rhythm, which would have enhanced skating programs.

Musicians play on an elevated platform in the central mushroom column during the 1872 Grand Fancy Ball at the Victoria Rink, Saint John, New Brunswick, by E.J. Russell. © Skate Canada (Photo: Greg Kolz)

Since competitors at the Olympics performed with live rather than recorded music, skaters were signalled to begin their programs with the dropping of a flag, and minutes were called by a referee for the duration of the program. If the musicians did not stop playing once a figure skater had finished their program, “time” was called, and the musicians would stop playing.

Lily Kronberger

The Hungarian figure skater Lily Kronberger was the first skater to use musical accompaniment at the World Championships. In 1911, she brought a military band from Budapest to play music by Hungarian composer Zoltan Kodaly to accompany her free-skating program.

Kronberger realized that proper artistic interpretation of Kodaly’s music would make her free-skating program shine, highlighting the technical challenge of the sport.

When did international figure-skating competitions become official?

When did international figure-skating competitions become official?

The International Skating Union was formed in the Netherlands in 1892; Canada became a member in 1894. The Union hosted its first amateur skating championship in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1896.